In 1957, Two Tiny Pellets Were the First Man-made Objects to Escape Earth’s Gravity

Eccentric astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky scored his victory just 12 days after Sputnik.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/e8/bfe8ef30-90fc-462d-bb43-aed8fc22815d/zwicky.jpg)

What if Jules Verne had been right, and you could fire a cannon and reach the moon? U.S. rocket experts, intent on beating the Soviets into space in the 1950s, actually tested a similar proposal. And in a way, it worked.

Fritz Zwicky offered a simple plan. Pack explosives into a ballistic missile, launch the missile, then detonate the explosive at high altitude. The resulting blast would accelerate tiny metal pieces into orbit. And once their orbit deteriorated, the little satellites, flashing like meteors upon hitting our atmosphere, could help scientists study reentry.

The offbeat approach promised a quick, cheap way to leave Earth—a kind of pop-gun rehearsal for launching real hardware. “We first throw something little into the skies,” Zwicky opined. “Then a shipload of instruments, then ourselves.”

The plan was perhaps as explosive as the genius behind it. Zwicky, an astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, was among the first people to study supernovas (a word he co-invented) and neutron stars, and even foresaw dark matter. He was also a leading pioneer in rocketry; during World War II he helped to develop the jet-assist rockets Allied aircraft used to make short-runway takeoffs, and he analyzed the German V2 rocket for wartime intelligence. Even so, he didn’t believe “complicated multi-stage rockets” should be the first step in reaching space.

But initial trials of his alternate, cannon-shot plan failed. A December 1946 launch, using a captured V2, fizzled: Astronomers scanning the heavens above New Mexico’s White Sands proving grounds reported no new lights in the night sky. Apparently, the hollow-shaped charges of Penolite explosive (adapted from World War II anti-tank grenades), which should have propelled the rocket’s payload into orbit, failed to ignite. A 1953 launch was planned, then considered too dangerous and scrubbed.

But on October 16, 1957, just 12 days after Sputnik, the plan finally succeeded. Lofted to 54 miles aboard an Aerobee sounding rocket, the Penolite charges detonated, propelling two pellet-sized probes beyond the pull of Earth’s gravity and into space. Harvard’s Super-Schmidt Meteor Camera recorded the triumphant moment. “I am certain they escaped,” Zwicky rejoiced, “and are now circling a long eclipse, around the sun.”

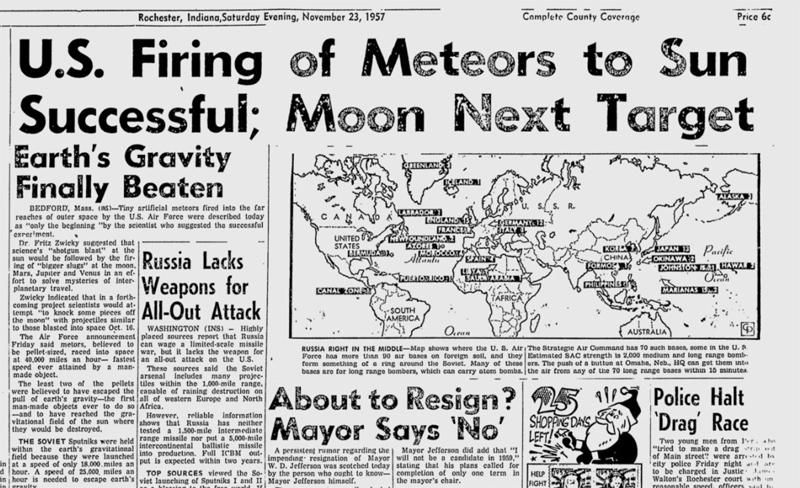

The feat garnered a headline worthy of science fiction: “Earth’s Gravity Finally Beaten!” The probes’ 25,000-mph escape velocity marked the fastest speed ever attained by a man-made object, and left Sputnik, traveling at a mere 18,000 mph, in the dust. Americans whose pride had been wounded in early October could even claim that, technically, they’d beaten the Soviets, having sent the first man-made object beyond Earth’s gravitational control.

“Science’s shotgun blast will be followed by the firing of bigger slugs at Venus or Jupiter, to probe interplanetary travel,” promised reports. Zwicky fantasized about a well-aimed volley “knocking some pieces off the moon” to enable the study of lunar composition. But with the success of Explorer I, the first American satellite, a few months later, mainstream rocketry quickly eclipsed exploding shells. So ended this alternate, almost steampunk method of reaching space.

Still, with its first launch attempt coming only months after the end of War World II, Zwicky’s could be considered the world’s first space program. And his “small can be useful” satellite design philosophy survives in today’s nanosatellite programs.