240,000-mile Filing Extension

“Dear Mr. Taxman: I’m sorry I missed the deadline. I was, uh, hmm, in a spaceship flying to the moon?”On the evening of April 15, 2010, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s John H. Glenn lecture series honored four legendary men of Apollo 13 on the 40th anniversary of their hair-raising …

"Dear Mr. Taxman: I'm sorry I missed the deadline. I was, uh, hmm, in a spaceship flying to the moon?"

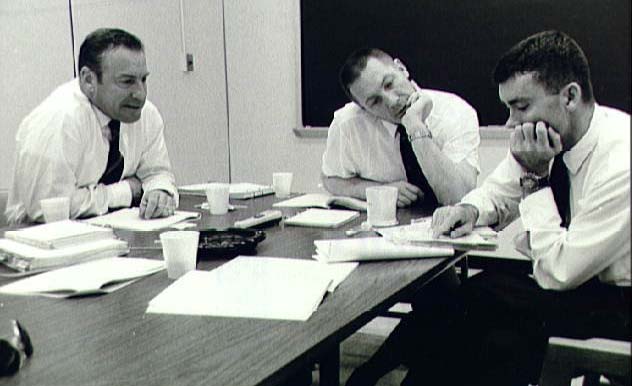

On the evening of April 15, 2010, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's John H. Glenn lecture series honored four legendary men of Apollo 13 on the 40th anniversary of their hair-raising flight: commander Jim Lovell, lunar module pilot Fred Haise, originally-assigned command module pilot Tom Mattingly, and flight director Gene Kranz.

Kranz and his Mission Control team brought the crew safely home against tall odds after an oxygen tank on the outside of the spacecraft exploded and turned the mission into the worst inflight crisis of the lunar program. Despite the aborted moon landing, Apollo 13 ranks with Apollo 11 and Apollo 8 as one of NASA's finest hours, often called "The Successful Failure."

The mission seemed hexed from the start. Just days before launch, the crew was exposed to the German measles. Mattingly, who carried no antibodies against the infection, was bumped on the possibility that he might develop measles during the flight. He was replaced by backup command module pilot Jack Swigert. Mattingly would fly to the moon on Apollo 16, and later commanded two space shuttle flights.

Swigert, who died of cancer in 1982, had 72 hours to get his head around the fact that he had just gone from an observer to a prime crew member, about to take his first rocket flight, and orbit the moon 240,000 miles away. A bachelor, he was on his own for any last-minute, to-do items at home. He launched with Lovell and Haise on April 11, 1970.

The first two days unfolded smoothly. "Let me mention something that happened just before the explosion," said Lovell at the Museum event, suppressing a grin. "And it concerns Jack Swigert. Things were working pretty nicely. The spacecraft was working perfectly. My two rookies were really doing a great job. And suddenly Jack looked at me and his face was white. And he said, 'Uh, when are we getting back to land, back on the Earth?' I said, 'Well, we're scheduled to land on the 21st.' 'When do we have to pay our taxes?' I said, 'Tax day is the 15th.' He said, 'I got on board this thing—I forgot to mail my taxes in!' We all had a big laugh, of course. And he says, 'I'm serious, they could put me in jail!' And the word got down to the control center, and everybody was laughing themselves silly, until finally someone called up and said, 'Listen, I think the president gave you a little relief because you're out of the country.' "

On the evening of April 15, 2010, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's John H. Glenn lecture series honored four legendary men of Apollo 13 on the 40th anniversary of their hair-raising flight: commander Jim Lovell, lunar module pilot Fred Haise, originally-assigned command module pilot Tom Mattingly, and flight director Gene Kranz.

Kranz and his Mission Control team brought the crew safely home against tall odds after an oxygen tank on the outside of the spacecraft exploded and turned the mission into the worst inflight crisis of the lunar program. Despite the aborted moon landing, Apollo 13 ranks with Apollo 11 and Apollo 8 as one of NASA's finest hours, often called "The Successful Failure."

The mission seemed hexed from the start. Just days before launch, the crew was exposed to the German measles. Mattingly, who carried no antibodies against the infection, was bumped on the possibility that he might develop measles during the flight. He was replaced by backup command module pilot Jack Swigert. Mattingly would fly to the moon on Apollo 16, and later commanded two space shuttle flights.

Swigert, who died of cancer in 1982, had 72 hours to get his head around the fact that he had just gone from an observer to a prime crew member, about to take his first rocket flight, and orbit the moon 240,000 miles away. A bachelor, he was on his own for any last-minute, to-do items at home. He launched with Lovell and Haise on April 11, 1970.

The first two days unfolded smoothly. "Let me mention something that happened just before the explosion," said Lovell at the Museum event, suppressing a grin. "And it concerns Jack Swigert. Things were working pretty nicely. The spacecraft was working perfectly. My two rookies were really doing a great job. And suddenly Jack looked at me and his face was white. And he said, 'Uh, when are we getting back to land, back on the Earth?' I said, 'Well, we're scheduled to land on the 21st.' 'When do we have to pay our taxes?' I said, 'Tax day is the 15th.' He said, 'I got on board this thing—I forgot to mail my taxes in!' We all had a big laugh, of course. And he says, 'I'm serious, they could put me in jail!' And the word got down to the control center, and everybody was laughing themselves silly, until finally someone called up and said, 'Listen, I think the president gave you a little relief because you're out of the country.' "