Cosmic Milestone: The End of the Line

Hubble has done it again, squinting deeper into the universe, and hence farther back in time, than ever before. What it sees is a little smudge of light that turned out to be the most distant galaxy ever detected, 13.2 billion light-years away. It’s not seeable in visible light, only in infrared. T…

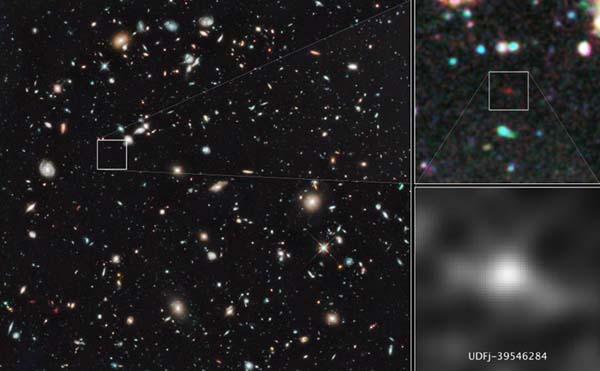

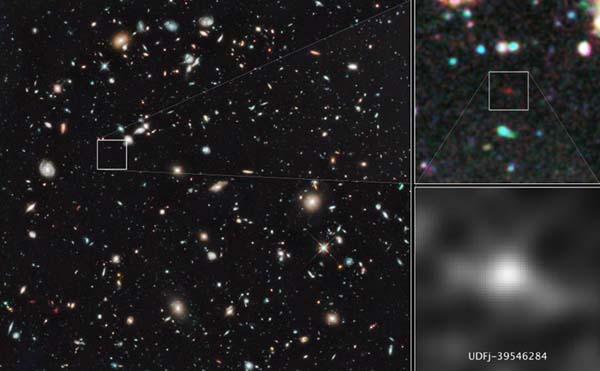

Hubble has done it again, squinting deeper into the universe, and hence farther back in time, than ever before. What it sees is a little smudge of light that turned out to be the most distant galaxy ever detected, 13.2 billion light-years away. It's not seeable in visible light, only in infrared. That's because the light waves that have traveled toward Earth for the past 13.2 billion years have been stretched, or redshifted, into the infrared end of the light spectrum.

So we see the galaxy, named UDFj-39546284, as it existed only 480 million years after the Big Bang. The new research was released in a Nature paper co-authored by Rychard Bouwens of Leiden University in the Netherlands and Garth Illingworth of the University of California at Santa Cruz. The team had previously found up to 60 galaxies about 170 million years younger, so this little galaxy, which was only one-hundreth the size of the Milky Way, seems to have existed in a lonesome place in a very young universe long before the Milky Way and billions of other galaxies formed.

The scientists say that this is it for Hubble's capabilities. "This is really about the limit for Hubble for directly seeing an object," says Illingworth. "It will take the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to go farther away."

That instrument, planned for launch in 2014 into an orbit around the sun, will offer another advance over Hubble's observing power, which has been revolutionary. "We certainly expect to have objects at greater than 13.2 billion light-years, or closer to the Big Bang than 480 million years," said Illingworth. "We saw a big change from 480 to 650 million years, but it certainly doesn't mean that there are no objects earlier than 500 million years. We expect that there are, and that they will go out to about 300 or so million years after the Big Bang." By that measure, the JWST will push our observing power about another 200 million years into the past.

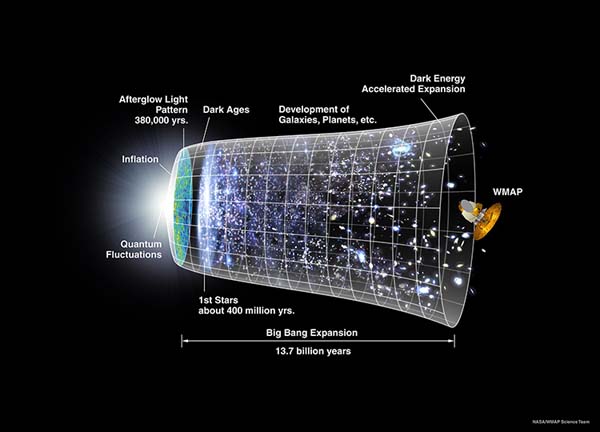

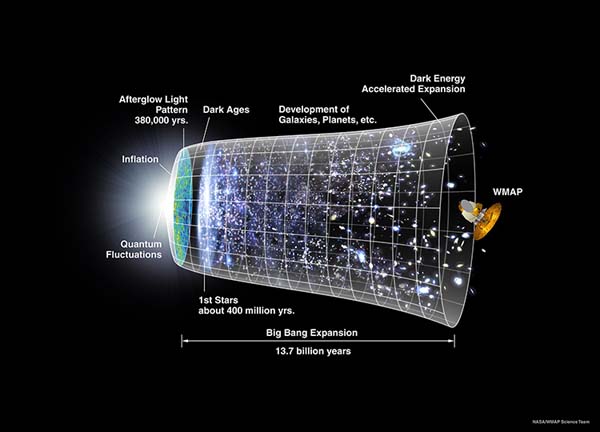

The crucial tool for dating the universe was the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, launched by NASA in 2001. "The WMAP mission and have very convincingly shown us—very independently—that the universe is really 13.7 billion years old," said Illingworth. "And so the first stars and galaxies must have occurred just 200-300 million years previously from this observation."

Illingworth feels confident that the 13.7-billion-year age won't budge as a result of the JWST. "I would be prepared to bet that astronomers' and physicists' current estimate of the age of the universe is really good. We know that better than we know about how galaxies formed in the early universe. So JWST may tell us lots more about dark energy and dark matter, but the age of the universe is already very well determined."

Meanwhile, the universe continues to expand at an accelerating rate, something discovered only at the end of the 1990s. So at some future point, the new (old) little galaxy will be 13.3 billion light-years away, and later, 13.4, and so on. "To see the first galaxies we will have to look ever farther back at later times," said Illingworth, "but 10, 20, 50, 100, or 1000 years doesn't make much of a difference. For humanity, it's effectively fixed."

So we see the galaxy, named UDFj-39546284, as it existed only 480 million years after the Big Bang. The new research was released in a Nature paper co-authored by Rychard Bouwens of Leiden University in the Netherlands and Garth Illingworth of the University of California at Santa Cruz. The team had previously found up to 60 galaxies about 170 million years younger, so this little galaxy, which was only one-hundreth the size of the Milky Way, seems to have existed in a lonesome place in a very young universe long before the Milky Way and billions of other galaxies formed.

The scientists say that this is it for Hubble's capabilities. "This is really about the limit for Hubble for directly seeing an object," says Illingworth. "It will take the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to go farther away."

That instrument, planned for launch in 2014 into an orbit around the sun, will offer another advance over Hubble's observing power, which has been revolutionary. "We certainly expect to have objects at greater than 13.2 billion light-years, or closer to the Big Bang than 480 million years," said Illingworth. "We saw a big change from 480 to 650 million years, but it certainly doesn't mean that there are no objects earlier than 500 million years. We expect that there are, and that they will go out to about 300 or so million years after the Big Bang." By that measure, the JWST will push our observing power about another 200 million years into the past.

The crucial tool for dating the universe was the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, launched by NASA in 2001. "The WMAP mission and have very convincingly shown us—very independently—that the universe is really 13.7 billion years old," said Illingworth. "And so the first stars and galaxies must have occurred just 200-300 million years previously from this observation."

Illingworth feels confident that the 13.7-billion-year age won't budge as a result of the JWST. "I would be prepared to bet that astronomers' and physicists' current estimate of the age of the universe is really good. We know that better than we know about how galaxies formed in the early universe. So JWST may tell us lots more about dark energy and dark matter, but the age of the universe is already very well determined."

Meanwhile, the universe continues to expand at an accelerating rate, something discovered only at the end of the 1990s. So at some future point, the new (old) little galaxy will be 13.3 billion light-years away, and later, 13.4, and so on. "To see the first galaxies we will have to look ever farther back at later times," said Illingworth, "but 10, 20, 50, 100, or 1000 years doesn't make much of a difference. For humanity, it's effectively fixed."