Farewell, Rosetta

The comet mission ends with a last hurrah.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/f2/94f2fda8-2cb6-4905-8d1f-6fb2d38d5cb3/comet_from_155_km_wide-angle_camera.jpg)

Europe’s Rosetta mission finally came to an end last week with the planned collision of the spacecraft with the object it had been monitoring for the last two years: comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Rosetta was on its sixth orbit around the Sun since launching in 2004, a journey that included three Earth fly-bys, one Mars fly-by, and two asteroid encounters. It also endured 31 months in deep-space hibernation before waking up in January 2014 prior to its arrival at comet 67P in August of that year. There it deployed the Philae lander, which achieved the first ever soft-landing on a comet (although in a sub-optimal location that resulted in lost communication).

Among the mission’s noteworthy scientific results were the discovery and analyses of gases streaming from the comet’s nucleus, which included molecular oxygen, nitrogen, and water. The water, though, was found to be enriched in deuterium (the heavy isotope of hydrogen), which means it isn’t the same type of water that exists today in Earth’s oceans. That in turn suggests that not all the water on Earth comes from comets, as one earlier hypothesis had held, and that a large proportion of Earth’s water must have derived from volcanic exhalations and mantle degassing early in the planet’s lifetime.

Taken together, Rosetta’s scientific findings so far indicate that the comet formed in a cold region of the early solar system more than 4.5 billion years ago, at a time when the planets were still forming. Thus, it contains some of the oldest material we can find, including amino acids, the building blocks of life.

During much of the two-year mission, many of Rosetta’s instruments were still too far away from the comet to do a detailed compositional analysis of 67P.

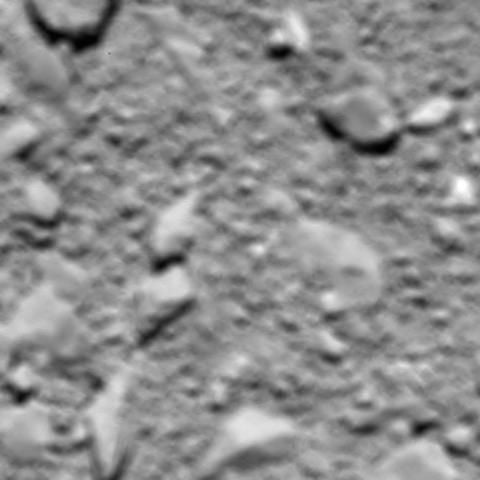

That changed when the spacecraft crashed into the comet last week, however; Rosetta’s last hours will most likely yield its most valuable scientific return. Not only are the final high-resolution images, some of them taken a few seconds before impact, stunning, the compositional analyses should be even more intriguing. We may have to wait years for the treasure trove of data to be fully harvested, however, and to gain a fuller picture of the organic content that comets likely delivered to early Earth, and their possible role in the origin of life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)