Five Things You Didn’t Know About the RAF

A book of trivia to celebrate the centennial of the first air force.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/6b/b16bba6e-8191-4201-a47d-435bcff01fdd/f-35.jpg)

It was September 15, 1940, and the Battle of Britain had been raging for 67 days. It was midday, and No. 504 Squadron had just been scrambled from RAF Hendon to intercept enemy aircraft heading in the direction of Buckingham Palace.

As Sergeant Ray Holmes took his Hawker Hurricane aloft, he thought fast. He set off in pursuit of the German Dornier Do 17s, shooting one down. As he targeted a second Dornier, he realized he was out of ammunition. In a desperate attempt to destroy the enemy aircraft, Holmes decided he had no choice but to ram it. At a closing speed of more than 350 mph, the Hurricane’s wing sliced cleanly through the Dornier’s rear fuselage, detaching it completely. Both Holmes and the German pilot parachuted from their aircraft; the Dornier ploughed into Victoria Station while the Hurricane crashed into Buckingham Palace Road—at nearly 400 mph—punching an enormous hole in the road. Amazingly, no civilians were hurt by either crash.

Sixteen-year-old Jimmy Earley was playing football nearby and raced over to where Holmes had parachuted. “He was still smiling. What a bloody hero to smash into a plane all that way up. We shook his hand and there were crowds of women all holding him and kissing him,” Earley recalled for The Independent 64 years later. The Hurricane was buried so deeply that it was easier to pave over the hole; it wasn’t until 2004 that the aircraft’s remains were excavated. The aircraft fragments are now on display at the Imperial War Museum.

This is just one of the stories in Scott Addington’s new book Reaching for the Sky: One Hundred Defining Moments from the Royal Air Force 1918-2018 (Uniform Press, 2018). The pocket-sized book, filled with information and lore, is perfect for an afternoon’s browsing. Readers will learn, for instance, that the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), which was founded in 1939 and ferried military aircraft from factories to maintenance units, and freed thousands of RAF combat pilots for active duty, had a rather unflattering nickname. “The ATA recruited pilots who were considered to be unsuitable for either the Royal Air Force or the Fleet Air Arm by reason of age, fitness, or gender,” writes Addington. “As a result the ATA was often referred to as ‘Ancient and Tattered Airmen.’ ”

Take the example of the evolution of the RAF roundel, the insignia used to identify military aircraft. Many readers will be familiar with its origin: “The famous RAF Roundel was originally devised during WWI when it became apparent that markings of some kind were needed on aircraft in order to avoid confusion between enemy and friendly machines,” writes Addington. “To this end, orders were issued at the end of August 1914 for the Union Flag to be painted on the underside of the lower wings on all British aircraft. This indeed worked well when the aircraft were at low altitude, but as soon as they started to fly a bit higher the Union Flag was often mistaken for the German cross.” Because of this, the French identification style of concentric circles was adopted. But what readers may not know is that the Stealth roundel to be used on the new F-35B Lightning II won’t be painted on; instead, the roundel will be part of the actual manufactured aircraft itself.

Do you know the difference between an “arse-end Charlie” and a “tail-end Charlie”? Addington’s handy list of RAF slang explains that an “arse-end Charlie” is the man who weaves backwards and forwards above and behind the squadron to protect them from attack. A “tail-end Charlie” is the nickname given to the rear gunner.

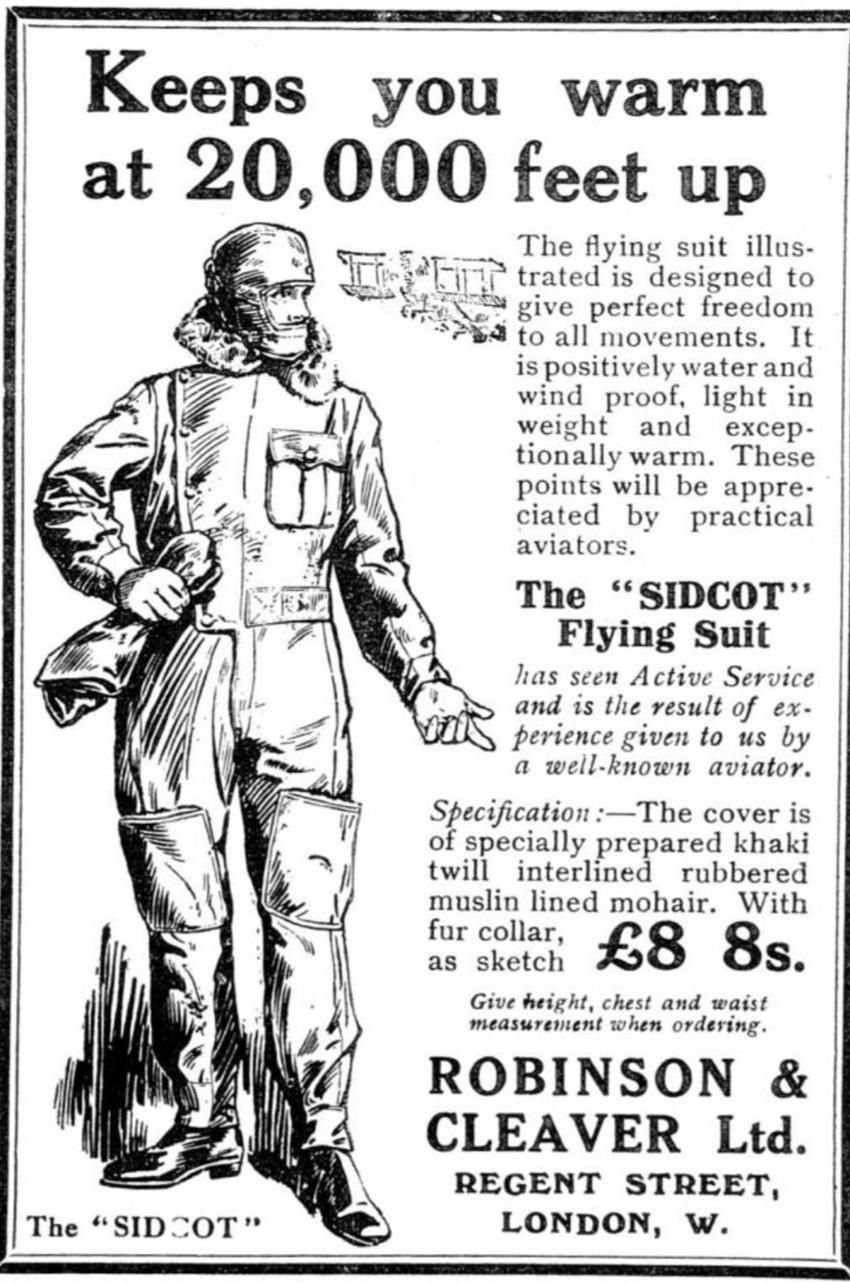

Our fifth and final item is the “Sidcot” suit, a flightsuit named for Australian pilot Sidney Cotton. In 1916, the Royal Navy Air Service pilot was scrambled after working on his aircraft. When he landed, he discovered that his oily overalls had kept him from feeling the cold, unlike all of the other pilots in his squadron. Cotton trekked over to the Robinson & Cleaver department store and commissioned a three-layer suit: a thin layer of fur; a layer of silk; and a waterproof outside layer. Within four weeks, the department store was making 1,000 Sidcot flightsuits a month. It was such a highly prized item, writes Addington, that it was the first item to be confiscated from British pilots when taken prisoner. The German ace, Baron von Richtofen, was wearing one when he was shot down.