Kepler’s First Planets

It’s nice when an expensive new machine works as advertised—nicer still when that machine has the ability to revolutionize a whole field of science.At this week’s meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, scientists couldn’t stop gushing about the exquisite performance of NASA’s K…

It's nice when an expensive new machine works as advertised—nicer still when that machine has the ability to revolutionize a whole field of science.

At this week's meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, scientists couldn't stop gushing about the exquisite performance of NASA's Kepler telescope, which was launched last March and is now staring at a field of 150,000 stars in the constellation Cygnus, looking for tiny (less than a hundredth of a percent) dips in brightness that signal the presence of an eclipsing planet.

"We are doing photometry at a level never seen before," said David Latham of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. And as the high quality of the data becomes apparent, "We're all burning the midnight oil seven days a week," to keep up, said planet hunter and Kepler team member Geoff Marcy of the University of California at Berkeley.

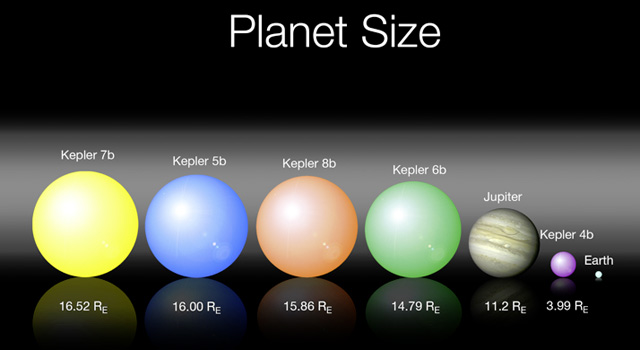

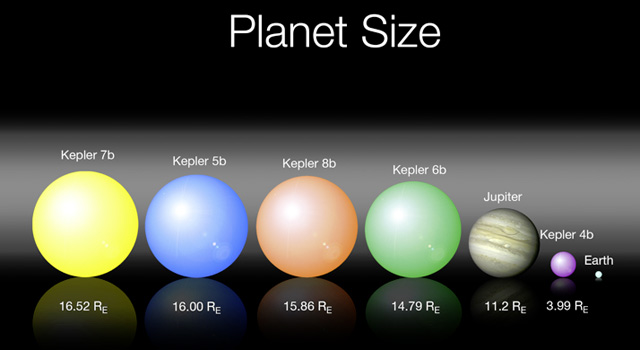

Kepler scientists announced the discovery of five new planets at the meeting, including one oddball with the density of Styrofoam. But perhaps more interesting were some of the objects that show unusual light curves but have yet to be identified. Until they're confirmed as planets or something else, the project simply calls these "Kepler Objects of Interest," or KOIs. KOI #74 and #81 are especially strange—only four times the size of Earth and the size of Jupiter respectively, they're both hotter than the stars they orbit. "Does anybody know what they are?" Latham asked an auditorium full of astronomers. Nobody ventured a confident answer.

It will take three years for Kepler scientists to confirm Earth-size planets circling stars at Earth-like distances (such orbits take a year, and astronomers need a couple of orbits before making a positive ID). But it's possible that small planets orbiting closer to their stars will turn up sooner in the data.

The real bottleneck will be follow-up observations from the ground. Just because a star's light dims periodically, it doesn't mean there's a planet. It might be another star in a binary system regularly crossing in front of its companion. The best way to tell the difference is with ground-based spectroscopy.

In the first 43 days of observing, Kepler turned up 175 KOIs—light curves that could indicate the presence of planets. Examination of the first 50 yielded 5 confirmed planets, but the other 125 in the queue are waiting to be followed up, and Kepler has been looking for several months since then.

We're going to have to be patient.

At this week's meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, scientists couldn't stop gushing about the exquisite performance of NASA's Kepler telescope, which was launched last March and is now staring at a field of 150,000 stars in the constellation Cygnus, looking for tiny (less than a hundredth of a percent) dips in brightness that signal the presence of an eclipsing planet.

"We are doing photometry at a level never seen before," said David Latham of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. And as the high quality of the data becomes apparent, "We're all burning the midnight oil seven days a week," to keep up, said planet hunter and Kepler team member Geoff Marcy of the University of California at Berkeley.

Kepler scientists announced the discovery of five new planets at the meeting, including one oddball with the density of Styrofoam. But perhaps more interesting were some of the objects that show unusual light curves but have yet to be identified. Until they're confirmed as planets or something else, the project simply calls these "Kepler Objects of Interest," or KOIs. KOI #74 and #81 are especially strange—only four times the size of Earth and the size of Jupiter respectively, they're both hotter than the stars they orbit. "Does anybody know what they are?" Latham asked an auditorium full of astronomers. Nobody ventured a confident answer.

It will take three years for Kepler scientists to confirm Earth-size planets circling stars at Earth-like distances (such orbits take a year, and astronomers need a couple of orbits before making a positive ID). But it's possible that small planets orbiting closer to their stars will turn up sooner in the data.

The real bottleneck will be follow-up observations from the ground. Just because a star's light dims periodically, it doesn't mean there's a planet. It might be another star in a binary system regularly crossing in front of its companion. The best way to tell the difference is with ground-based spectroscopy.

In the first 43 days of observing, Kepler turned up 175 KOIs—light curves that could indicate the presence of planets. Examination of the first 50 yielded 5 confirmed planets, but the other 125 in the queue are waiting to be followed up, and Kepler has been looking for several months since then.

We're going to have to be patient.