Flying the Mail in Remote Idaho

Neither tight canyons, nor wildlife on runways…The postman’s creed is slightly different for pilots delivering mail in the mountains.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/e8/8fe805dc-6d18-493b-a12e-c821d9466907/12a_sep2017_badleyranchhillyrunway_live.jpg)

When we approached the first mail stop, Ray Arnold rolled his Cessna 206 up on its left wing and spiraled down inside the narrow canyon that funnels Big Creek past Taylor Ranch. Bare ground the color of a cougar’s hide filled the front window. The airspeed was slow, the bank was steep, and my senses were on high alert: One bad turn and we could hit the mountain, or fall into the creek. But Arnold’s hand was steady and he rolled out just above the rushing water. Another turn revealed a smaller creek and the twisted grass strip of the University of Idaho’s Taylor Wilderness Research Station.

Arnold touched down and rolled toward the bend in the runway where caretakers Meg and Peter Gag waited for us by their mailbox with their six-year-old daughter Tehya, their dog Bitsy, and a pile of cargo: the recyclables they were sending back; a cooler, for transporting perishables from the grocery store; and a few pieces of luggage for their day trip to Boise, where Tehya had a doctor’s appointment.

Arnold and the Gags off-loaded the bright orange mailbag, a stack of eight-foot lumber, a furnace, a week’s groceries, and other supplies. Gag strapped his daughter’s car seat into the Cessna as she rooted through the mailbag for birthday cards and presents from grandma.

To reach Taylor Ranch from Cascade, we flew 70 miles above central Idaho’s nine- and ten-thousand-foot peaks, snow-covered national forests, and fire-ravaged slopes. Arnold pointed out backcountry landing spots as we passed; some snowy white stripes in a sea of evergreens, others no more than dirt scratches on the face of bare hills.

Each time he indicated a landing site, he recounted a close call some pilot had experienced there: a ski plane upended in deep snow, a nosewheel grabbed by a gopher hole. But the mail must go through.

The U.S. Postal Service contracts with Arnold Aviation to deliver to U.S. Forest Service outposts and some two dozen ranches in the Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness Area of south-central Idaho. The USPS has negotiated with contractors since before the stagecoach days, and it operates like a restaurant owner who knows that waiters can live off their tips. A mail pilot survives not on what the postal service pays him but by using the mail run to also carry passengers, cargo, and weekly deliveries.

**********

Arnold’s route is unique in the United States. Alaskan bush pilots also fly the mail to remote villages, but they give it to postal representatives or lock it in sheds for pickup. They do not deliver to individual homes or boxes.

The Idaho route is run by the U.S. Postal Service. “These deliveries are part of the postal service’s universal service obligation to cover the nation, ensuring that all users of the mail receive a minimal level of postal services at affordable prices,” says John Friess, a USPS spokesperson. “Arnold Aviation delivers mail twice a week—once a week in the winter—to ranches scattered across more than two million acres of wilderness. The area is designated a primitive area, and no vehicles can be driven on it.”

Arnold has been flying this mail route for 40 years and has taken off and landed at each strip more than 2,000 times. At the Taylor Wilderness Research Station, where he flies in and out with scientists, students, and, sometimes, specimens of the wild wolves and mountain lions that they study, his arrivals and departures have numbered closer to 4,000.

On one of those flights he had a close call with a departing caretaker who insisted that a planeload of her books had to fly out with her. “Before Taylor Ranch had a snow blower to clear off the runway, they used to just pack the snow down,” Arnold said, “and that day it was slushy. I took off in the Cessna 185 on wheels with a load too heavy for the conditions. Before I had flying speed I flew right off the bank and put the nose down to accelerate. I felt the tailwheel hit the water. Big Creek is not that wide, and there was a tree across the river. I could not get over it, so I stayed low. When I got to it, I had to lift my wing to get past it.”

Ranch owners and caretakers who live on private land in the remote region count on Arnold’s weekly mail delivery. He picks it up from the Cascade post office and delivers it to individual mailboxes on a rural route much like ones along country roads elsewhere in the United States. Except here there are few roads. For much of the year, flying is the only reliable way in or out.

Mail has been flown into backcountry Idaho since 1928, but in the 1950s two mail routes developed to serve isolated Idaho ranches, hunting camps, U.S. Forest Service stations, and mining locations. In 1975, Arnold Aviation consolidated the two routes into one and assumed responsibility.

He and his then-wife Carol started Arnold Aviation in 1972. Before that, Carol had taught home economics at Cascade High School until their daughter Rhonda was born; Ray taught math and science there. But he traded the classroom for the cockpit, where lift vectors, crosswind components, density altitude, and weight and balance calculations were not just variables in theoretical problems but matters of life and death.

During the days I spent at Arnold Aviation in February 2015, parcels arrived from FedEx and UPS. Meat and groceries piled up in the cooler and walk-in freezer. Carol Arnold, now divorced from Ray, manages the office, makes appointments for folks who come in off the river, and takes orders for things they want delivered. Carolyn Smith, the company’s shopper, runs errands and fills the orders. Everything is weighed and marked with initials for the various ranches: Yellow Pine Bar, Mackay Bar, Badley Ranch, Shepp Ranch. At daybreak Arnold collects a large bin full of mango-colored mailbags at the Cascade post office, and everything is carefully distributed in the airplane for balance and convenience.

In the spring, summer, and fall, when the ranches are humming with guests, the loads are full and the hours long. Passengers fly in and out with the mail, and everyone is too busy to chat. There are 20 stops along the two flying routes, flown on alternating days; 13 stops the first day and seven stops the second.

The winter run is more leisurely, a one-day, five-stop trip to the few caretakers and owners who live along the rivers all year long. Approaching our stop at Yellow Pine Bar, we flew down low and followed the S-turns of the Main Salmon River. The airstrip was a snowy blaze among tall pine trees at a bend in the river midway along the section most popular for river rafters, a swift-moving 80-mile stretch with rapids from Corn Creek to Vinegar Creek. The strip was slushy and icy.

Yellow Pine Bar is a private ranch that’s been owned by the same family for more than 60 years. In the summer, it’s a stop for rafters and jet boaters, who buy drinks and snacks and sometimes knives or tools from caretaker Greg Metz’s blacksmith shop.

Sue Anderson, who has worked at Yellow Pine Bar as a caretaker since the 1980s, rode up on a four-wheeler, its tires wrapped in chains. She gave Arnold a hug, a kiss, and homemade fudge. Jim Mozingo, from nearby Allison Ranch, was visiting. After they unloaded mail, groceries, water jugs, and garden mulch, Arnold sat between the Cessna’s open cargo doors, eating fudge and chatting.

As we headed back down the snowy runway, Arnold said, “This is where a deer jumped out of the woods, onto the runway and through my propeller one day on takeoff.” In a split second the deer was sliced to pieces and a propeller blade was knocked loose. Arnold shut down, then sent for a mechanic, and a new propeller. “That was a $12,000 deer.” He took off, turned upriver, and flew over the snowy strip at Allison Ranch. “Another deer ran out here and hit me when I was already in the air,” he said. “That was a $700 deer.”

In summer Arnold picks up the mail at 6 a.m. and gets going right after breakfast. In winter he takes off when it gets light, but fog kept us grounded that day until nearly one o’clock. It was well into the afternoon before we got to the last three stops. Mackay Bar, like other river ranches, thrives on guiding and outfitting hunters, fishermen, trail riders, and ranch guests. Its caretaker, Buck Dewey, apologized for having turned off the coffee pot as the hour grew late. “Next time there’ll be coffee and cookies,” he promised.

Our next stop was the Badley Ranch airstrip, on the side of a hill that climbs from a 10-degree slope to a 17-degree one. At the top, Arnold pulled off onto a semi-level rocky spot, and Luke Badley rode up on a four-wheeler, chased by his black and tan coonhound Danner. The dog sniffed my legs while the men unloaded. Badley opened his groceries and handed a Fat Boy ice cream bar to Arnold, who accepted it and ate it as if it were the reason we landed there.

“All these strips are private,” Arnold said. “You can’t land on any of them without permission.” I looked down at faint tire tracks sweeping up the hill and imagined learning to land on a slope like this. Arnold made it look easy, but I’ve landed on a few, much more gradual up-slope strips, and I knew it was difficult.

Once we were airborne again, we stayed just off the water. At Shepp Ranch, horses scrambled over the end of the runway. We circled and waited for them to clear off.

“One day a backhoe was in the middle of the runway and the driver never budged,” Arnold told me as we circled. “So I landed short and rolled right up behind him, put on the brakes, and ran the engine all the way up. The backhoe driver nearly jumped out of his seat.”

While Mike Demeres rounded up the horses, Arnold explained that the postal service calculates his pay by a flat-map rate. They are unmoved by complaints about extra miles flown around fog banks, the added cost to climb out of valleys, minutes tacked on waiting for heavy construction equipment, dogs, or horses to clear the runway.

When I flew with Arnold two years ago, he was 78, but when he spoke of retiring it did not sound imminent. He loves flying in these mountains, seeing sunsets, lakes, snow-covered peaks, elk, bighorn sheep, and the rivers. Mostly he loves the people.

Mike Dorris, whose father Bill was one of Arnold’s airmail-flying instructors, is one of the pilots who sometimes flies mail for Arnold. He lives in McCall, where he has his own delivery route, usually driven by truck. But in the winter months, when the highest mountain passes are snowed under, he takes to the air.

One morning Dorris took me on his mail route in his polished silver Cessna 170, landing atop two feet of snow. To get the landing skis down prior to takeoff, he’d pumped a broom-like lever up and down 53 times. You only use them when absolutely necessary—the skis have no brakes.

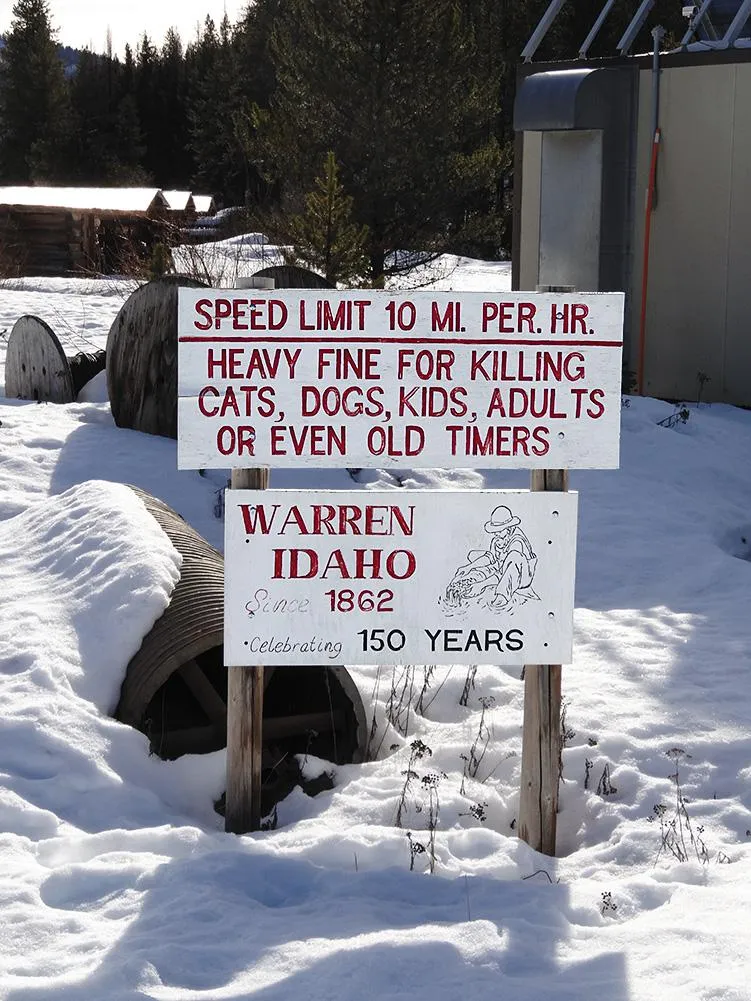

In Warren, the elevation is nearly 6,000 feet, and the snow there lingers. From the air, most of the 20 or so buildings looked tidy and well kept, but next to the airport, rusted roofs and missing boards gave Warren the look of a ghost town. Postmistress Jan Munsen rode over from the town’s tiny post office with mail cartons strapped to the front of her four-wheeler, followed by a tall, thin man looking for groceries we did not have.

Dorris grew up in a family of 13 kids, flying and skiing. In the 1970s he was a two-time member of the U.S. Ski Team. He raced in Europe, coached, went pro, then came back to start a flying company with his father. Now he and his wife Leslee own Sawtooth Aviation in McCall.

“My dad always cussed the mail route,” Dorris recalled. “Planes slide off the hill, the ski plane especially. You can retract the skis, but it’s time-consuming. So you start out visiting with someone and the next thing you know your airplane’s slid backwards into the bushes.”

His father taught him and three of his brothers to fly, often reminding them that his own 10 worst flying experiences were on skis and sometimes urging them not to use them. Still, every pilot learns the hard way.

Using skis on the steep Badley Ranch strip one day, Dorris turned around at the top of the hill. “Then the nose got pointed downhill and started tracking toward a yellow pine,” he said. “I blasted the tail up, turned it left, went through tree branches, got going downhill, missed a big rock, hit a pile of backpacks and ski equipment, and tore up a guest’s skis, but got airborne.”

At the South Fork Ranch, we dropped off supplies, mail, and a case of beer that caretakers Tim and Judy Hall had won in a Super Bowl bet from their fellow caretakers at Yellow Pine Bar. Dorris and the Hulls swapped local lore, including the tale of an old-timer who ordered whiskey jugs every week until he went blind and shot himself—in the heart instead of the head, to leave less mess for the friend whom he knew would likely be the one to find his body.

At the McClain Ranch we chatted with Tom Roberts, whose grandmother Sylvia McClain bought the ranch in 1946. Roberts moved there with his mother when he was nine and recalled the long-ago day Arnold landed with a strong wind on his tail and hit two lodgepole pines off the end of the strip. The airplane stopped so suddenly that the engine flew off. Nobody was hurt, but a man in the back seat panicked, climbed over Arnold, and jumped out the window. The trees were later removed and the runway extended.

Before we flew back to McCall, Dorris landed at Willey Ranch, the steepest runway in Idaho—550 feet long at a 23-degree incline. One day his wheels got stuck in snow there, halfway up the runway. He and his passenger took turns holding the brakes to prevent the aircraft from sliding backward while the other man dug a path through the snow for the wheels.

Dorris used to deliver mail to Willey Ranch until someone burned the house down smoking in bed. He’d taken me there just to share the thrill. Imagine flying toward a mountain, then instead of turning, crashing, or climbing, you pitch the nose up just enough to land on it.

Dorris was a teen when Arnold took flying lessons with his father. When Arnold had to step down for a year and a half for medical reasons, Dorris flew his route for him.

Dorris told me how you need strict rules for yourself flying in the mountains. “You have to be 110 percent sure before you turn up a canyon. If you get complacent and lose track of which drainage you are in, all of a sudden the ground climbs real steep and goes up into an overcast. The river you were following turned a different way back behind you and now there’s no room to turn around.”

I thought of the first, dramatic turn in that canyon with Arnold the day before, and the skill it took to make it, and the sacrifices these pilots have made throughout their lives to see that the mail gets through. Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds, reads the U.S. Postal Service creed. Arnold and Dorris don’t fly when it’s snowing, but they live up to the sentiment.