The Seabee Keepers

With a devoted international following, an exceptional amphibian still creates buzz.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/72/bd726c12-090c-4fa5-b5ff-74cbffaa5cc5/10t_am2017_seabeec-film_0159_live.jpg)

It was a special day. I was 10 years old, and my father had arranged for me to take my first ride in an airplane. My dad had a friend—a big, smiling ex-U.S. Army aviator—who owned a Republic RC-3 Seabee. It was a summer afternoon in 1958, and I can still remember the moment the chubby little seaplane lifted off from the local airport. I was sitting behind the pilot, and I peered through the Seabee’s large passenger window and watched the houses below grow smaller. After flying around for about an hour, we landed on a nearby lake.

More than 50 years after my memorable flight in Republic Aviation’s versatile amphibian, Seabees staged a special flyby at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s annual fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. At the 2015 event, 17 Seabees showed up. “They came from all over the U.S. and Canada, the most I’ve ever seen in one place,” says Steve Mestler, a Seabee enthusiast who helped organize the gathering. “We were supposed to do two passes, but because Seabees are so slow, they limited us to one. It was still great.”

Harry Marchant, the big-hearted man who took me up in his Seabee, had flown Piper L-4 spotter planes in Europe during World War II. Like thousands of returning G.I. pilots, he had found a way to continue flying after the war. An avid outdoorsman, Marchant saw Seabees as the ideal sportplane, tough enough to operate from primitive grass strips and rough water. By the mid-1950s, he was finally able to afford one.

Home-ported at Maine’s Auburn-Lewiston Airport, Marchant’s Seabee was situated for quick hops to remote lakes and good fishing. My father, a machinist, helped him maintain the airplane. Having grown up during the Depression, my dad never dreamed that someday he and his blue-collar friends would be flying off on fishing trips. “We’re living like Rockefellers,” he liked to say.

**********

In 1944, Republic Aviation's president, Alfred Marchev, was a worried man. Formerly known as Seversky Aircraft, Republic had struggled financially prior to World War II, but boomed during the war years by manufacturing thousands of P-47 Thunderbolts. With the war’s end nearing, Marchev felt it essential that Republic diversify; he wanted to end its reliance on military contracts and get into commercial aviation.

Banking that returning airmen would want to fly as civilians, Republic foresaw a market for a family airplane—a go-anywhere, low-cost amphibian versatile enough to whisk folks to cities for business or to a vacation spot on a quiet lake. For any chance of success, however, the company needed to produce an airplane selling for around $3,500—something just above the price of a deluxe family car. Former P-47 test pilot Percival Spencer thought he had just the thing Republic was looking for.

Spencer came from a family of inventors (his father, Christopher, had invented the Spencer repeating rifle). In 1914, after salvaging, rebuilding, and then soloing in a Curtiss-style flying boat soon after his 17th birthday, he began to dream of perfecting an affordable amphibian. Many years of hard work later, he had a flying prototype, the Spencer S-12 Air Car, which he sold—along with the manufacturing rights—to Republic.

Republic’s engineers transformed Spencer’s wood S-12 into an all-metal pusher plane called the RC-1 (Republic Commercial) Thunderbolt Amphibian. Spencer first test-flew the prototype in November 1944. The U.S. Army was impressed with its rugged utility and ordered a dozen, designated OA-15s, for rescue work.

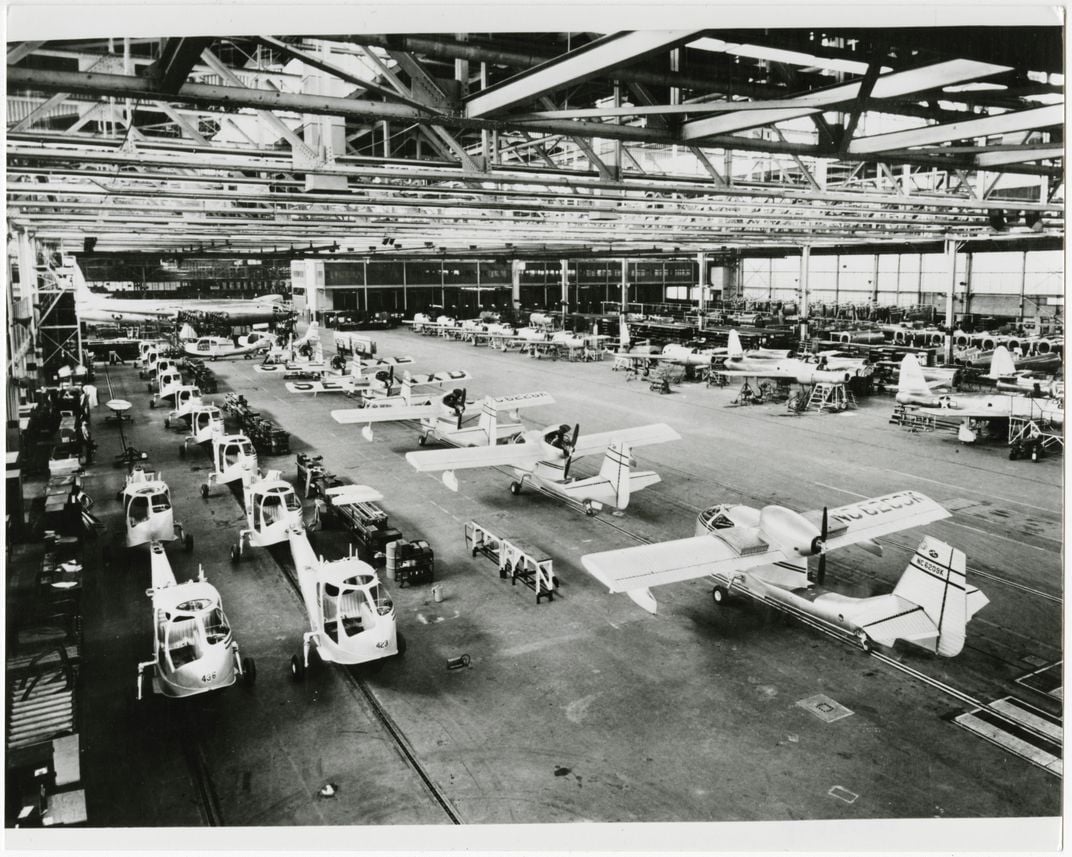

Marchev feared that using traditional aircraft construction methods would make the Thunderbolt Amphibian too costly for the postwar market. A production specialist, he wanted to incorporate automobile production methods and use common auto parts whenever possible to lower manufacturing costs. He established a team of engineers to redesign the Thunderbolt amphibian so it required fewer parts and could be manufactured faster. The re-engineered craft was now called the RC-3 Seabee.

Republic initially offered the Seabee for $3,995 ($52,995 in today’s dollars)—including a two-way radio. Stylish magazine ads trumpeted the airplane’s utility and proud fighter heritage. No less an authority than Wolfgang Langewiesche, the author of the legendary Stick and Rudder, evaluated the RC-3 in the February 1947 issue of Air Facts magazine and praised Seabees as “surely the most versatile airplane ever offered—at a price one can hope to afford.”

North American Aviation, manufacturer of P-51 Mustangs and other warplanes, had also built a personal aircraft for the postwar market. Called the Navion, it was a sleek, attractive four-placer that Popular Science magazine billed the “junior edition Mustang.” It was also speedier than the Seabee, but it wasn’t amphibious, and at $6,250 was more expensive.

Seabees were built for comfort, not speed—and not glamour. The bulbous fuselage tapers into a slender tail boom, giving them the look of tadpoles with wings. Some consider them ugly. Owners, however, appreciate spacious cabins that offer superb visibility. In addition to two side doors, the amphibian has a door in the nose, which enables a copilot to stand and snag a buoy and offers passengers easy egress to docks.

Stable in flight, Seabees also handle nimbly afloat, especially when equipped with an optional reversible-pitch propeller. Beaching is easy: Merely lower the gear after splash down, and power up a ramp or onto a suitable beach. Popular variety-show host Arthur Godfrey, an experienced light-airplane pilot, sang the Seabee’s praises on his radio programs. RC-3s sold the world over, and by mid-1946 deposits for the amphibian had soared. Republic couldn’t keep up with demand.

That first postwar year, 1946, was an exceptional one for America’s general aviation manufacturers: They delivered over 30,000 airplanes. Alas, for Republic, what should have been a banner year was marred by problems with its production line. To be profitable, Seabees had to be built in large numbers. At war’s end, however, the companies responsible for supplying machinery crucial to efficient Seabee production were behind schedule. Consequently, the first 175 Seabees had to be essentially hand-built, resulting in greatly increased labor costs. Prices were raised to $4,995, then $5,995. After each increase, demand waned.

By mid-1947, the specialized tooling was finally set up, and production increased. But it was too late. The postwar economy had softened, diminishing overall demand for light aircraft. Adding to Republic’s woes, after V-J Day, the Army canceled its contract for OA-15s. In 1947, with the company running out of cash, Republic executives made the decision to terminate Seabee production. Before production ended at Republic’s Farmingdale, New York factory, many of the approximately 1,060 amphibians built were exported. The airplane became a popular air-taxi workhorse, especially in Scandinavia, where there were relatively few airports but lots of water. One RC-3 was even pressed into service with the fledging Israeli air force; others flew with the French military in Vietnam.

**********

Raised on Long Island in the 1950s, Steve Mestler grew accustomed to Seabees buzzing constantly overhead. “They were plentiful then,” he says. While watching “Jungle Jim,” a 1950s TV show in which a Seabee made cameo appearances, he resolved that someday he would own one. To young Mestler, the peculiar airplane suggested adventure.

Today, Mestler, a retired United Airlines captain, not only owns a Seabee but runs a Seabee club website (republicseabee.com) from his lakeside home in South Carolina. The popular website supports an active international community of Seabee owners by providing announcements of upcoming events, maintenance tips, and sources for parts. “Parts can be a problem since the plane was last built in 1947,” says Mestler. “Good Seabee mechanics are few and far between, so if you own one, you better know how to turn a wrench.”

Retired commercial pilot Skip Neidhardt, 84, of Rye, New Hampshire, spent 20-plus years instructing in seaplanes. After owning and operating several Seabees, he is partial to the type’s rough-water capability. “Seabees can take a lot of punishment,” he says. He maintains there is nothing else like them on the market. Of today’s carbon-fiber amphibians, he says: “They’re expensive, and not built for commercial activity.”

The Seabee is tough enough to survive a wheels-up landing on a runway, which usually causes little damage. A wheels-down water landing, on the other hand, can be disastrous, with the airplane capsizing instantly as the wheels dig in, forcing occupants to struggle free of a flooding cabin. Neidhardt thinks most amphibians have been lost this way, making them among the costliest of light aircraft to insure.

“There’s a certain breed of pilot attracted to Seabees,” says Bruce Hinds, another retired airline pilot and longtime Seabee owner. “Fact that it’s a taildragger and a boat is a big draw.” And Hinds likes the solid feel of the airplane: “It’s stable, fun to fly, with all-around visibility nearly as good as a helicopter.” What makes a Seabee especially controllable on water—the reversing propeller—is also handy at airports, where Hinds delights in dazzling onlookers. “I like the looks I get when I back into my parking spot,” he says. “Gives everyone ‘reverse envy!’ ”

While shopping for an airplane, Hinds had checked out the latest amphibian designs, but after watching a promotional video for another amphibian, his wife had declared that airplane “too delicate.” Then, after flying in a Seabee, she proclaimed: “I want one of these.”

Based in Port Orchard, Washington, Hinds says most of his destinations are airports, but both he and his wife value the freedom offered by the Seabee’s water capability. They like flying into remote Idaho grass strips with friends and camping under the wing. “We swap campfire lies and do some hangar flying,” says Hinds. “Next day, we’ll fly to a nearby lake and run her up on the sand for a picnic.” Although some lakes don’t allow seaplanes, most do, and a general rule of thumb is: If a lake is open to powerboats, it’s open to seaplanes.

Tommy Bartlett, a 1950s-era Midwest entertainment personality and former Army instructor pilot, got to exploit the Seabee’s rough-water capability during a daring rescue on a cold September day in 1950. On a joyride over Chicago’s Lake Calumet, Bartlett and three friends were heading back to Meigs Field when they spotted four heads bobbing amid whitecaps near an overturned boat.

With 29-mph winds whipping up formidable waves, conditions for a rescue weren’t ideal. Knowing that the people in the frigid water below wouldn’t last much longer, Bartlett carefully set his craft down near the survivors. While maneuvering his sturdy flying boat within arm’s reach of the swimmers, his passengers pulled a pregnant woman aboard. As he tossed lifejackets to the remaining swimmers, passenger Stewart McDonald, a professional water skier, yelled out, “Help’s coming.”

Overloaded with five people aboard, and with water breaking over the bow during takeoff, Bartlett was relieved by how quickly his Seabee got off the lake. Back at Meigs Field, he dropped off two passengers and brought the young woman to a waiting ambulance. Bartlett returned to the lake for another difficult landing, after which McDonald hauled a now-unconscious man into the cabin for the trip back to Meigs. The U.S. Coast Guard rescued the remaining two men.

As reported in local newspapers and the June 1951 issue of Flying magazine, within an hour of sighting, all four boaters were recovering in a hospital.

Longtime Seabee mechanic and pilot Henry Ruzakowski notes that seaplane pilots respect the level of flying expertise and seamanship needed to operate a Seabee. “It’s a big airplane that requires real piloting skills,” he says. “It can be a handful to taxi in crosswinds.” Ruzakowski points out that the pilots drawn to the Seabee are those looking for a challenge.

Known informally as “Mr. Seabee,” Ruzakowski has made his living for 35 years repairing and restoring RC-3s. His father worked on the amphibian’s production line as a mechanic back in 1946, and would later fly his own Bee for 38 years. “I inherited a passion for Seabees from my dad,” he says. “It’s part of family history.”

Finding parts for a 70-year-old airplane—one whose manufacturer is no longer around—requires a Seabee mechanic to be well connected. “I know guys who have parts, and can still find pretty much everything we need,” says Ruzakowski.

With its original 215-horsepower Franklin engine, Seabees were reputed to be underpowered. However, Ruzakowski estimates that half of the remaining RC-3s have been retrofitted with more powerful Lycoming engines. He notes that although they greatly enhance a Bee’s takeoff and climb performance, they “don’t increase speed much because of airframe drag.”

“Fly at only 100 mph?” says Ruzakowski. “No problem. Seabee guys aren’t in a rush to get anywhere. It’s all about the fun.”

A Seabee in good shape with a Lycoming already installed runs about $65,000. But “to get the plane you want,” says Ruzakowski, with new avionics, paint, and upholstery, expect to spend another $40,000 to $50,000.

It was John Knapp’s idea to proclaim 2015 “The Year of the Seabee” at the seaplane base at Oshkosh. Knapp, an Experimental Aircraft Association rep and seaplane judge at the base, has never owned a Seabee, but thought something should be done to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the first flight of the “ugly duck.” “Guys who restore those old Seabees are a class act, and great to be around since they’re having so much fun flying their planes,” he says.

For years airline captain Edgar “E.T.” Tello has been flying his Seabee to Oshkosh from his home in a North Carolina airpark. Ever since seeing a Seabee in a James Bond movie as a young kid, Tello has been captivated by the “weird-looking planes,” and enjoys sharing the fun by giving rides to folks visiting the seaplane base. Among his favorite passengers at the 2015 fly-in were Women Airforce Service Pilots and their grandkids. “These women can still fly,” he says, after one made two water landings. “And they’re all in their 90s.”

Mestler, who named his ship the Ol’ Marty B, estimates there are 40 to 50 flyable RC-3s in the United States, with several others operating around the world. With their distinctive profile, they “are always popular at airshows,” he says. “Whenever I land at airports, I plan on an hour or two on the ground. Invariably someone walks up and says, ‘What the heck is it?’ ”

Although I had occasionally sighted Seabees stashed away at airports around the country, I hadn’t been aboard one since my first flight, in 1958. That is, until Seabee owner Bill Whitney kindly hosted a visit to his pristine Bee, based on New Hampshire’s Mendum’s Pond, in the summer of 2015.

Whitney, 82, lives the Seabee ideal: His airplane is parked on a ramp beside his lakeside home. Climbing aboard brought back memories of my first flight, and that long-ago thrill of landing on a lake.