School of Hard Rocks

Loni Habersetzer teaches pilots how to land on the harshest terrain.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/hardrocks-0308-631.jpg)

From a thousand feet, the Alaskan tundra is a verdant landscape broken only by rivers winding down to Bristol Bay. Loni Habersetzer banks his Piper Super Cub steeply over one of the rivers. He circles once, twice, then descends for a closer look.

What's the matter?

The airplane is now low over the water, the wingtips seeming to brush tall spruces nearby. Habersetzer turns to follow a sharp river bend. He's found a place to land, he tells me.

Ahead is a bar covered with pieces of driftwood and boulders the size of basketballs.

Land?

Habersetzer cuts back the power. The airplane's tires skim water, throwing up rooster tails of spray.

We're not landing, we're crashing.

The airplane bounces up onto the bar and jolts to a stop. Habersetzer turns to me. "Great, isn't it?" he asks, grinning.

Habersetzer specializes in landing on difficult places: narrow gravel bars, steep mountain slopes, rock-strewn glaciers, rough beaches, muddy bogs, stamp-size clearings. Depending on the conditions, he can land and take off in an area as small as 100 to 150 feet, a little more than five airplane lengths. Other bush pilots land and take off from challenging terrain, but they do it for practical reasons, to deliver cargo or carry passengers to and from remote areas. Habersetzer flies into unwelcoming places purely for sport, pushing the limits of his ability and the performance envelope of his airplane.

Habersetzer shuts down the engine. The only sound is that of the river rushing by. He gets out of the airplane and surveys the rock bar, pacing its length. It is barely longer than a railroad boxcar. Habersetzer knows within just a few feet the length he needs for takeoff. Here, he will run out of solid ground, but by that point he thinks he will have enough speed and enough lift under the wings for the airplane to safely hydroplane along the water until he can get it airborne.

Habersetzer clears a couple of large rocks and a log, then walks back to the airplane. After starting up the engine, he applies a careful combination of throttle and rudder to gently swing the airplane around. Then he again powers the engine to lift the tail before releasing the brakes. In a couple of bounces he's at the end of the bar. The airplane briefly skims along the water, then lifts into the air.

A man with a gentle, easygoing manner, Habersetzer does not appear to be bent on self-destruction. Lanky and tall and wearing wire-rim glasses, he looks almost bookish. Born in Vancouver, "Warshington," as he pronounces it, Habersetzer practically grew up in a Super Cub, and he has never flown any other type of airplane. He soloed in his father's as a teen. After high school, he supported himself working for his father's electrical contracting business; on weekends he built up his flying hours, and later he began spending summers flying for an Alaska hunting lodge and guide service.

Like most Cub pilots, Habersetzer learned the traditional method for landing a taildragger: Line up with the runway, cut the power, then glide until the airplane touches down softly to a three-point landing, in which the tailwheel and the main-gear wheels all touch at the same time. It is, says Habersetzer, a perfectly fine way to land, if one has the real estate. But he found that the traditional method has two big drawbacks. First, the wind and other conditions will make you land on a different spot every time, and sometimes, Habersetzer wanted more precision, especially when he saw a good spot for hunting or fishing. Second, once the tailwheel touches, you lose nearly all forward visibility, a dangerous situation when you're in close to objects like rocks and trees.

"I met a guy from Alaska who had quite a bit of bush flying experience," Habersetzer says. Instead of gliding, this pilot flew a power-on approach, slowing the airplane to the verge of a stall, then using the throttle to control the rate of descent and the elevator to control pitch and thus airspeed. By flying "behind the power curve," Habersetzer explains, he could drop his airplane on the exact spot he wanted.

Nothing special there. It's the same technique naval pilots use to land on carriers. The revelation to Habersetzer was that the technique doesn't just let him put the airplane right on the spot he wants, it also enables him to keep the tail up longer, which improves visibility.

Habersetzer honed his skills, hopscotching from one landing strip to another, sometimes making as many as 30 or 40 landings in just a couple of hours. Gradually, he added his own touches to the power-on method. He found that by putting 30 pounds of weight in the tail section, he can brake harder after touchdown without flipping the airplane on its back. He learned to use his GPS unit to determine groundspeed on touchdown so he can calculate his rollout distance. He discovered that during his takeoff roll, applying flaps in increments results in less drag than full-on flaps and thus enables a shorter takeoff run. And he figured out how to perform a "water-assisted" landing, in which he slows the airplane by skimming the tires along a stream or lake before rolling onto solid ground.

Habersetzer insists that he's no daredevil, that what looks crazy is in fact the result of careful planning and a lot of practice. "If there is any doubt [about being able to make a landing]," he says, "I'm just not interested in doing it."

When he finds a new place to land, the first thing Habersetzer does is double-check his position—that is, in which direction he will need to hike should he become stranded. He then checks out the airspace above the strip, descending in 300-foot intervals. During this survey, he determines the approach to the strip and checks for obstacles such as trees or power lines. In addition to the length and width of the strip, he pays attention to its surface. He may "drag" the strip, flying its length and letting the airplane's tires roll along the surface. Before deciding whether he will land, Habersetzer may overfly a strip as many as 15 times.

After we've been flying for a while, Habersetzer lands on the crest of a low ridgeline. It is a comparatively easy strip: mostly flat, unobstructed by trees, the ground free of large obstacles—perfect for practicing. Habersetzer places a set of caribou antlers off to the side to mark a touchdown point. We take off and Habersetzer sets up for approach. With constant manipulations of the throttle, he works to keep his speed over the ground at 43 to 45 mph. "A one-mile-per-hour difference in groundspeed can mean another 25 to 50 feet to stop," Habersetzer says.

Just as he is alongside the antlers, he cuts the power, dropping the airplane onto the surface. The wheels roll over the gravelly surface and he pumps the brakes to bring the airplane to an abrupt stop. Habersetzer checks his rollout distance: a little over 120 feet. Not satisfied, he decides to go around for another approach.

Much of what he does, Habersetzer explains, depends on the equipment he flies. The Super Cub, with its large wing, its high power-to-weight ratio, and its tough, simple design, is ideal for backcountry flying, a fact Cub drivers have known since the airplane's 1949 rollout. And "the airplane is so responsive you almost wear [it]," Habersetzer says. "You get a lot more feedback from the controls."

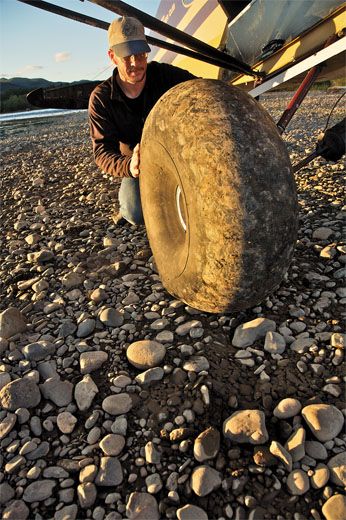

Just as important are the tundra tires (Habersetzer never flies with skis or floats). They are larger than normal tires, and kept at low air pressure, so they don't roll over obstacles as much as through them. Manufactured by Alaska Bushwheel at a tiny factory in Joseph, Oregon, the tires come in several sizes and sell for as much as $4,500 per pair. Once marketed primarily to commercial operators in Alaska or Canada, the tires are now sold to all kinds of pilots, around the world. As more recreational pilots discover the pleasures of off-airport flying, says Alaska Bushwheel president Bill Duncan, airplanes like the Super Cub are becoming "the new sport utility vehicle," and tundra tires as much a status symbol as a practical necessity.

Other necessities, says Habersetzer, are a shovel, a saw, and a good axe, in case the pilot finds himself needing to extend his runway. "At that point, you have all the time in the world," he says. When Habersetzer's airplane got bogged down in the mud once, he spent the afternoon cutting down spruce trees to lay down for an impromptu strip.

In 2003, having noticed that backcountry flying was becoming increasingly popular, Habersetzer decided to start teaching his techniques to other Super Cub pilots. He began his own business, Cubdriver749er (based on his airplane tail number, N82749). Not being certified by the Federal Aviation Administration as an instructor, he cannot offer dual instruction in his airplane, so students have to be licensed pilots and provide their own Super Cubs. Habersetzer offers courses in Alaska, in Washington state, or at a pilot's home, in packages starting at $1,500.

At the beginning of his course, he sits down with his student and describes his flying techniques. He then demonstrates them in his Cub while the student rides as a passenger. Finally, the student solos an approach in his own airplane, while Habersetzer talks to him via radio. At each step, Habersetzer ratchets up the challenge, advancing through the basics of landing on rough surfaces, steep slopes, and soft sand or mud.

Just as important, Habersetzer spends a lot of time telling students what not to do—for example, not being tempted by a spot that has enough room for landing but may not have enough for takeoff. By the end of the course, Habersetzer explains, students should have the ability and confidence to go out and learn on their own.

One Habersetzer alumni, Shaun Lunt, praises his instructor's example: "Loni's very consistent, very smooth," he says. Lunt, a 33-year-old anesthesiologist from Loma Linda, California, is a 12-year pilot who, after working his way up the ratings and endorsements—private, instrument, commercial, floatplane, aerobatics—decided he needed a new adventure. He co-owns a Cirrus SR-22, and last winter he bought a Super Cub with the intention of flying it to Alaska. "I have a passion for the outdoors, and bush flying was something I had been interested in doing," he says. Last May, he flew to Alaska to take the course. "I had flown on skis and floats, but nothing this demanding," he says. "It's a very aggressive way of flying, very precise."

The most valuable aspect of Habersetzer's instruction, Lunt says, "is that you get the benefit of a lot of experience that would have taken a lot of time and a lot of mistakes to learn otherwise…. It takes a lot of the 'school of hard knocks' out of it."

Early on in his instruction business, Habersetzer had thought about making a video, something that might entertain as well as get his service some exposure. He had seen some other backcountry flying videos; he thought he could do better. But knowing nothing about video production, he shelved the idea. Then in 2004, friend and flying partner Greg Miller asked Habersetzer for help making a short video for a line of custom tires Miller was going to promote at the annual Alaskan Airmen's Association convention. "I had Loni shoot me bumping around a few places," Miller recalls. "It was basically a seven-minute loop, something to draw a little attention to the product in the display booth." The video ended up being the talk of the show. "I had people lined up outside the tent," Miller says. "People who had been flying 30 or 40 years in Alaska who came up to me to say they had never seen anything like it—and these are people who you'd think would be blasé about the whole thing."

Thus inspired, the two spent a couple of months in 2004 shooting video of themselves flying in the mountains. "The production quality was pretty rough," Habersetzer admits, "with just some hand-held camera from the ground and some air-to-air shots, along with some shots [from a camera] mounted on the fuselage of the airplane." Watching it, I was reminded of TV footage of snowboarders careening down mountainsides and kayakers paddling over waterfalls. Released on DVD in 2005 with a title only Freud could love, Big Rocks and Long Props has sold nearly 5,000 copies—an impressive number, considering the filmmakers have done no advertising or promotion, and have sold copies almost solely via the Internet. A second DVD came out last year, and Habersetzer has recently finished a third, on glacier flying in Alaska.

"It's opened a lot of opportunities for me that I never would have expected," Habersetzer says. Since the videos came out, pilots in Kenya and Mexico have paid him to come teach them his techniques, and he will be traveling soon to Israel and New Zealand to instruct more pilots. His customers are, like him, in it for the challenge.

It's late now, and as the sun drops, long shadows stretch across the landscape. Habersetzer heads toward another low ridge of hills. The ground quickly rises toward the airplane, but he makes no attempt to climb. He adds a notch of flaps. Then he suddenly adds power and pulls the airplane up. The Cub is following the grade of the hillside, and as it loses speed, it nears the ground. With a gentle bump, it touches down, rolling to a stop just as the hill peaks.