The Gold-Plated Cabin

There aren’t many companies that can make an airliner fit for a king.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Skilled_Flash_Today_FM10.jpg)

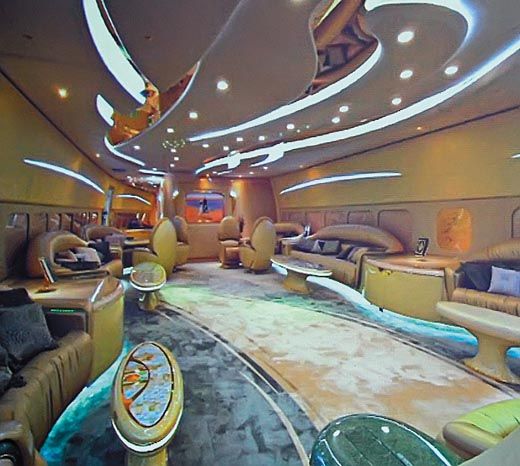

Engineers at Lufthansa Technik recently faced a tough problem: How do you install a 300-pound bronze racehorse in a large private jet? The client insisted that it be secured to the cabin floor by only one leg. Solving that type of problem can make a company’s reputation in the demanding business of creating aircraft interiors for the wealthiest individuals in the world.

Luxury completions, one of the services provided by aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul facilities, is a global business, and currently one of the healthiest sectors of the aircraft industry. In one particularly active center, at EuroAirport near Basel, Switzerland, three companies employ 3,000 workers to complete new aircraft or to refurbish gently used ones, a process that can last two years and add 10 tons of innards to a hull that either arrives hollow or is gutted after it lands.

EuroAirport is one of the more unusual airports in Europe. Though it is situated entirely on French soil, just inside France’s border with Switzerland, it is operated by both countries. Its location in the tri-national area of Alsace (the German border is not far away) is part of the marketing strategy for the three completions companies it hosts. They take advantage of the Swiss, French, and German reputations for precision and Old World craftsmanship to promote their abilities to install fine furnishings.

“In the French Alsace, and nearby in Germany, we have all of the talent we need in one area,” says Heinz Köhli, one of the founders and chief executive of AMAC Aerospace. “That makes Basel unique.”

The newcomer of the three firms, AMAC opened its completions center in November 2008 with 180 craftsmen. The company expects to double its workforce by this June, when it will have completed construction of a second hangar. The orders for completions that have compelled AMAC and its competitors—Jet Aviation Basel and Lufthansa Technik Switzerland—to hire more employees arrived one to three years ago, when profits in the oil, mineral, and metals markets peaked, and newly rich magnates and governments bought airplanes. Aircraft sales have since slowed or stopped, yet each company, with a backlog that will keep it busy for several years, has been hiring. “At the moment the market is at a standstill, but I see stable growth for completions,” says Köhli. “A year ago we would have said Russia has the most potential, but our main customer is now African governments, and we have some high-net-worth individuals. Some of them produce vodka, for example. But you cannot focus on a particular industry or region for growth.” Certainly most at EuroAirport expect little business from the United States, where the economic downturn hurt corporate aviation more than it did in Europe.

In an AMAC conference room last spring, Köhli and Ruedi Kurz, who oversees maintenance and production, looked at a graphic representation of their company’s work-in-progress. A box of flat, black, magnetic airplanes was mounted on the wall next to an illustration of an AMAC hangar floor. An airplane silhouette was placed on every patch of floor, and each silhouette was marked with a tail number. To the right of the graphic, a glossy panel bore a blueprint of a cavernous new hangar AMAC was building. A year before that hangar’s completion, its floor was also full.

“We did our build-out a year ago when the world was different,” said Köhli. “Thank God we already have our pipeline of orders, and that we are lean and flexible.” Kurz motioned to a real Airbus A320 in the hangar. “The customer signed the completions contract with us,” he said, “though at the time, this site was nothing but cornfields.”

The A320, which has since been delivered, had its registration number painted over, and when I got ready to take a photograph, I was directed to make sure that the tail number of its black miniature counterpart didn’t show. Companies in the global completions business protect their clients’ identities. Have your aircraft finished by any of these firms, and that’s between you, a production manager, and a mushrooming family of specialists that includes woodworkers, upholsterers, plumbers, leather craftsmen, and engineers.

Most craftsmen start in the more mundane area of the business—the maintenance, repair, and overhaul that keep aircraft flying. They often then move up to finish the interiors of new commercial airliners. The most skilled workers build out the cabins of luxuryliners for wealthy individual clients.

“Our commercial work is still high-quality of course, but it’s fitness for a particular purpose,” says Clark Goodison, a Scotsman who manages the master craftsmen in the production support shops for Lufthansa Technik Switzerland. “You get on and off an airliner within two hours. You have your sandwich and the seats are comfortable enough. But the Sultan of Brunei, who might fly his aircraft four times per year, wants everything to be perfect. The VIP completion is about the precision. It’s the quality, it’s the finish, and a lot of the feel is artistic. Our staff look three times at a task before they decide to do it.”

To ensure consistent trade skills and promote a company culture, Lufthansa Technik launched an apprentice program more than 50 years ago. This year, some 800 apprentices, ages 16 to 20, work in its German plants. Some, after completing internships subsidized by the German government, will work under a master for months to years before taking on a less supervised role in the company.

Karl Eikelmann is the senior director of production at Jet Aviation Basel. “We tell recruits that in cars you only do production, and it’s always the same work. Here, you don’t see the same work twice,” says Eikelmann. Most of the 60 specialists in the Jet Aviation upholstery shop came from automotive factories (a common recruiting ground for all three companies). The shop sews every stitch needed in the aircraft cabin, from the carpet to the sofa to the window shades to, for the very particular client, a fine fabric lining for dresser drawers.

Before any of the craftsmen begin work, however, interior designers determine the clients’ needs and desires. The consultation ordinarily takes months.

“Most customers know that they can’t bring their home designer and their yacht designer and directly translate that to their airplane,” says Bernd Schramm, AMAC’s chief operations officer. Every fabric or veneer, along with its adhesives, varnish, or paint, has to be certified by aviation authorities, who will subject the materials to burn tests. A material—leather, for example—is exposed to a flame for 12 seconds. In that period, it must not catch fire. If it ignites after that, it must extinguish itself without intervention in less than 15 seconds from the moment of ignition, or the material cannot be used on an aircraft. If leather is mated with adhesive and veneer to form a headboard or office chair, the combination of materials must remain non-flammable for a full minute of exposure to fire, and any flame that appears after that must also burn out within 15 seconds.

“The most difficult to pass a burn test is animal horn,” says Eikelmann at Jet Aviation. “And we have to burn-test every material, including stone veneer, which is the newest idea for vanity tops.” The veneer, made of minute flakes distilled from rare quarries, can be as thin as 3.2 millimeters, and is affixed to a featherweight metallic honeycomb. The stone veneer passed the burn tests.

Completions firms try to accommodate all requests. “Some customer may ask that all the controls on his main chair in the cabin for the entertainment system be transferred from the right to the left side, and that’s just fine with us,” says Lufthansa’s Goodison. “Maybe he wants to sip his champagne with the other hand.”

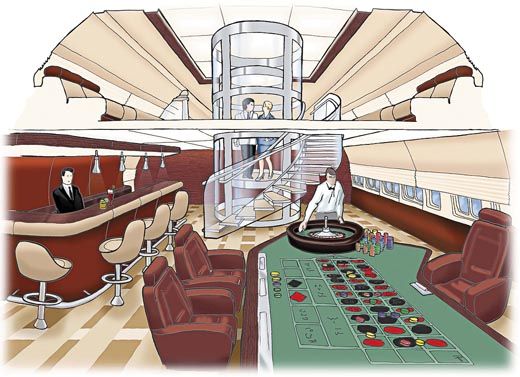

Part of the process may include constructing a full-size mock-up in white Styrofoam, right down to the king-size bed, conference room, and gourmet galley, to help the customer’s designer picture the floor plan. At Jet Aviation, such a mock-up costs $600,000 on average, and stays intact just long enough for a walk-through. Since most design is proprietary, and many furnishings unique, the mock-up is then destroyed.

Some requests just can’t fly. Lufthansa Technik had to reject a Middle Eastern client’s demand for an open flame in the cabin, reminiscent of a nomadic desert campfire. The company offered an alternative—an electrical appliance that created an artificial fire—but the project was abandoned. Jet Aviation worked exhaustively to craft a sofa designed like an immense seashell, but could not build it to meet weight and height requirements, or the regulation that such seats must withstand 9 to 16 Gs.

But Lufthansa was able to make one dream come true: a night sky rendered in tiny diodes, to imitate a constellation the customer had enjoyed one special evening.

Once the aviation safety requirements have been met, the craftsmen must meet a very high standard of quality. All work performed is checked, and checked again. Employees watch for the tiniest smudge on fabrics as they move from delivery dock to factory shops, and an elevator with a special speed for full loads prevents even a gentle bounce at the bottom to keep from damaging delicate furnishings.

Many of the finishes are exotic. Eikelmann holds out a patch of steel-gray skin from an ocean stingray, which an Asian customer wants on his chair.

“Bubinga wood seems to be the thing now,” says Clark Goodison, who as an amateur musician first saw the rare and costly grain on African drums. One project at Jet Aviation required a team of artists from Eastern Europe be flown in for six weeks. They hand-painted a decorative pattern on a roll of Alcantara (a suede-like material) running 45 feet along the cabin ceiling.

“The most expensive finish is gold plate, but any finish can be costly depending on how many curves,” says Eikelmann. Curved surfaces require more care to align with other layers as well as the underlying honeycomb of the furnishing and adjoining fixtures, and they take many more hours to seal and polish.

How much does it all cost?

Lufthansa Technik offers a completion for the Airbus Corporate Jet or the Boeing Business Jet, with a cabin starting at six million euros ($8.5 million). A high-end completion can add $30 million to a hull that costs $60 million empty, according to director of marketing and sales Thomas Foth.

“Of course this depends on the materials,” explains AMAC’s Ruedi Kurz. “One customer wants mother of pearl inlay on all of the cabinets. Another wanted all of the carpets to be silk, and that’s another half-million right there.”

“Smaller business jets can be completed in the lower eight-figure range,” says Wolfgang Reinert, a spokesman for Lufthansa Technik. “The bigger an aircraft is and the more individual a customer’s wishes are, the more expensive it will be.” Wide-body hulls, such as the Airbus A340 or the Boeing 747, “can reach the nine-figure range.”

No figures have been confirmed for the completion of the so-called “Flying Palace,” a $320 million Airbus A380 with an interior designed by British firm DesignQ for Saudi Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal. One aircraft interior design firm estimated that finishing the two-level, 6,000-square-foot interior will cost $150 million.

Such high-profile projects—Prince Al-Waleed made headlines by becoming the first individual to purchase the enormous Airbus—may be good for business, but AMAC’s Schramm says that word of mouth is the completions firm’s best marketing tool.

“The customers know each other, and they know each other’s pilots,” says Schramm. “They go to the Gulfstream operators’ conference and the other operator groups. They go to EBACE [a European trade show]. They know who is getting service at each of our competitors.”

“I have customers contacting me, I have never contacted or heard of them,” says Ruedi Kurz. “It’s a different kind of corporation than a typical U.S. one. In these regions, it’s more like a private family operation.”

Although all three companies at EuroAirport have a backlog, they compete vigorously for VIP customers. David Stewart, a partner with the forecasting company AeroStrategy Ltd, estimates that only five percent of worldwide maintenance, repair, and overhaul spending is for completing VIP aircraft. That means companies are chasing a piece of approximately $3.3 billion a year, and maybe another $1.5 billion for refurbishing and upgrades.

In a market where money appears to be no object, what makes a customer choose one company over another?

“We would not try to compete with others in this industry on price,” says Schramm. “We would go by our quality and by the guarantee of our on-time delivery. We have comments from our customers that they feel taken care of, like a concierge service in a good hotel. Especially people in the Middle East, they want to come during our Christmas or New Year holiday and you have to find a way to support them.”

Says Foth at Lufthansa Technik Switzerland: “We have an ambitious turnaround goal of four weeks for a VIP refurbishment. That’s 4,000 man-hours to remove all of the cabin, repair all of the components and re-install. There’s a dedicated team for each part. Even a base maintenance on a VIP cabin in this time is very ambitious. Generally [maintenance alone takes] six to eight weeks.”

How a company presents itself, says Lufthansa Technik’s Wolfgang Reinert, can also influence customers. When prospective clients visit the firms at EuroAirport, they see uniformed craftspeople at work. At Jet Aviation, the company uniform is an Old World-style French smock in navy blue. By contrast, the AMAC shop has a preppy J.Crew look: khaki shirts and gray trousers. At Lufthansa Technik, master craftsmen with special functions, like shift supervisor, wear white.

“You don’t want to brush against a soft hide in a dirty uniform, and dark colors hide that dirt,” says Lufthansa’s Goodison in a sly poke at the others.

Managers repeatedly emphasize that their company’s competitive edge is the quality of work, and quality depends on the skills of the engineers and craftsmen. Anja Reichardt, Lufthansa Technik manager of personnel marketing and recruiting, says that if her company can’t recruit enough workers for the demand from the aviation industry, it will hire workers from similar professions like yacht construction and completing. What she looks for in a worker is accuracy as well as creativity and a sense of responsibility.

In addition, the company is trying to recruit the best workers through cooperative exhibitions and activities with schools and universities and through media campaigns targeting a range of ages: Some seek to interest seven-year-olds in the basic concept of flight; others try to lure older students to start an engineering career with the company.

“We’re trying to make aviation sexy,” says Reichardt. “We put a lot of effort in the branding.”

Lufthansa Technik, for example, is assisting with the restoration of a 1950s-era Lockheed L-1649A Super Star. The aircraft is important to the company because in 1958, it became the first airliner operated by Lufthansa capable of crossing the Atlantic without refueling.

In Europe, the aviation industry competes for engineers and craftsmen with the automotive industry. In surveys in which engineering students have stated preferences for places where they’d like to work, Lufthansa Technik is in the top 10 choices, but still falls behind the German automobile companies BMW and Porsche.

AMAC executive Heinz Köhli picked up skilled workers from automaker Peugeot, which last year cut thousands of jobs from its plants. Cutbacks at air force bases in both France and Germany also sent a stream of talent, he says.

“Everyone is stealing engineers from everyone else,” says Bernhard Conrad, Lufthansa Technik’s chief technology officer. The main challenge for the aviation industry, he says, is that “aviation begins with a fence around it, while you can go with your dad to the car dealer and see the oil being changed.”

After the Berlin Wall came down and the Eastern bloc’s aviation industry fell idle, Lufthansa Technik took over the Berlin-based, 500-worker maintenance facility of the former East German airline, Interflug. Conrad was impressed by how quickly the workers became adept at repairing Western aircraft. “The massive insufficiency of spare parts in Eastern Europe,” he says, developed in the workers “excellent repair expertise and great flexibility.”

Ingenuity may be the most important qualification for workers in the luxury completions industry today. That 300-pound bronze racehorse? Lufthansa Technik engineers found a way to install it in the private jet and still meet all the safety requirements.

Roger A. Mola is an Air & Space researcher.