The Rocketbelt Caper

A true tale of invention, obsession, and murder.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rocketbelt-hero_blue.jpg)

In British author Paul Brown's book, Houston-based friends who scramble to raise the funds to design, build and fly their homebuilt jet backpack, which they call the Rocketbelt 2000. Before long, though, the friendships sour to the point of death threats. There are money troubles, thefts, assaults with a hammer, nights in jail, a kidnapping, and rascals on the run, Texas-style. When one of them becomes the victim of a horrific murder, an entertaining story becomes a shocking thriller. The Rocketbelt Caper was published in the U. K. in 2007, and will be rereleased this summer in the United States. The following excerpt is reprinted by permission of the author.

In British author Paul Brown's book, Houston-based friends who scramble to raise the funds to design, build and fly their homebuilt jet backpack, which they call the Rocketbelt 2000. Before long, though, the friendships sour to the point of death threats. There are money troubles, thefts, assaults with a hammer, nights in jail, a kidnapping, and rascals on the run, Texas-style. When one of them becomes the victim of a horrific murder, an entertaining story becomes a shocking thriller. The Rocketbelt Caper was published in the U. K. in 2007, and will be rereleased this summer in the United States. The following excerpt is reprinted by permission of the author.

It was just past midday on a January Sunday in 1995, and Brad Barker was getting nervous. It was warm and dry, but grey clouds were gathering overhead. A light breeze whipped at the long grass that ran along the edges of the runway. The water in the airport's sea-lane rippled and mirrored the dull sky. Barker strode out to the runway in white sneakers, jeans and a denim shirt, a cellphone clipped to his belt, and a pair of unnecessary sunglasses perched on his nose. Around him, a handful of colleagues busied themselves with preparations. This was supposed to be the beginning of the dream, but just one mistake could turn it into a nightmare. And what the hell would he do then?

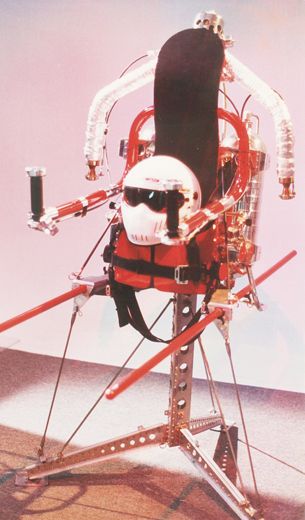

He'd tested it, of course, as much as you could without strapping a man into it and blasting him into the air. Now it was time to do just that. Barker looked at his pilot, bespectacled and slightly out of shape, wearing a white helmet and a jumpsuit. Barker was sure he had the right man for the job. Bill Suitor was nothing if not experienced. He'd flown these things hundreds of times before. Suitor wouldn't have agreed to do this unless he thought it would work. And there was no reason to think it wouldn't. That's what Barker told himself as he strapped Suitor into the Rocketbelt 2000.

It had taken five long years and several hundred thousand dollars to reach this point. Was it an obsession? You could say so, as the idea of building a rocketbelt had dominated Barker's thoughts ever since he first saw the amazing device, in a James Bond movie, as a nine-year-old boy. There had been sacrifices made, friendships lost, legal wrangles, and a bunch of other stuff he didn't want to think about right now. It had been quite an ordeal, but that was all in the past. Barker slapped Suitor on the back and retreated to a safe distance.

The pilot offered a thumbs-up, and there was a silent moment of anticipation. Barker studied his 'Pretty Bird' - its lovingly polished fuel tanks, curved exhaust pipes and control handlebars he'd worked so hard to put together. It was a unique device, but it looked oddly familiar, being as it was the realisation of a childhood fantasy. Then Suitor twisted open the throttle. The test flight began.

It was the noise that hit the small band of onlookers first. A high-pitched wail – an explosive scream of superheated steam, as loud as a jet engine. It was an assault on the eardrums, like having an aerosol fired into each ear. And this from a device not much bigger than a portable vacuum cleaner, strapped to the pilot's back like a hiking rucksack.

A white cloud of steam erupted from the exhausts, kicking up a swirl of dust around the pilot's feet. And then – in a defining moment for Barker – pilot and machine lifted into the air. There were no wings and no strings. This man was flying solely on the power of the rocketbelt.

Suitor hovered for a moment, a couple of feet from the runway, then maneuvered out over the sea-lane, blasting a spray of water into the air. He banked into a graceful circular flight path, increasing his altitude to ten, fifteen, thirty feet. Barker watched the figure of the rocketbelt pilot silhouetted against the sky, his shadow becoming increasingly longer on the runway below. It worked. It really worked. And all Barker could think was, when do I get a turn?

Fuel was limited, and the flight needed to be short. So Suitor arced back towards his starting point, and began his descent. The landing was feather-light and perfect. The pilot bounced on tiptoes, steadied his feet, then offered Barker a salute.

'Yeah!' whooped Barker. He rushed over to congratulate the grinning Suitor, and said, 'Let's fuel it up and go again.'

So they did, and the second test flight was just as successful as the first.

Then, on the third flight, things began to go wrong. In fact, if the truth were known, things had been going wrong for quite some time. They would get a lot worse before this whole sorry affair was over. And it was all because of one of the most sought after and revered machines in the history of flight. It was all because of the amazing rocketbelt.

Blame Buck Rogers, and James Bond, and Commando Cody, and the Jetsons. It was their fault that everybody wanted a rocketbelt. The iconic device was a ubiquitous feature in twentieth century science fiction. It became pivotal to the accepted vision of the future. Eminent science writers like Isaac Asimov confidently predicted that, by the year 2000, the citizens of Earth would be zipping about through the air using rocketbelts. That never quite came to pass. Brilliant inventors did build a small number of working rocketbelts, and a handful of pioneering pilots got to fly them through the sky. But, for most of those who coveted rocketbelts, the device remained tantalisingly out of reach, a technological holy grail.

Then Brad Barker and two of his friends got sick of waiting for science fiction to become reality. They formed a fractious partnership and set out on an ambitious quest to build their very own rocketbelt. Perhaps the least incredible thing about their story is that they actually succeeded in building and flying a working rocketbelt – in fact the very best rocketbelt that had ever been built. Then the incredible dream turned into an almost unbelievable nightmare.

For now, Barker was watching his rocketbelt fly through the air, grey skies closing in, wind brushing the back of his neck. Suitor circled over the sea-lane, and swung back around to the runway, but he came in too fast. Much too fast. His feet clipped the tarmac and flipped him around, hard onto the ground. The rocketbelt hit the runway at pace, too, with a sound like a car hitting a lamppost. The pilot cut the throttle and lay still on the tarmac. Miraculously, Suitor was unhurt, if a little shaken. Barker rushed onto the runway to check out the damage.

'The thing damn near killed me,' said Suitor, crawling to his knees and unstrapping himself from the device.

'You damn near killed my rocketbelt,' said Barker. He ran his hands along the dented stainless steel he'd spent so long polishing. Goddamn it, this would take months to repair. And it was not as if Barker didn't already have enough problems to deal with.

A few spots of rain began to land on the tarmac. Barker hoisted up the rocketbelt and loaded it into his trailer. He would have to put his plans for a public demonstration flight on hold for a while. Then, once the belt was repaired and public flights were arranged, the money would begin to roll in. Finally, he would be able to forget about his troubles. That's what Brad Barker reckoned. In fact, Brad Barker's troubles had barely even started.