What Happened to Pan Am Flight 7?

Sabotage? Negligence? Fraud? New clues surface in a 60-year-old aviation mystery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/4b/494bf3f8-4ce5-4576-90fd-3ee6a00b7acc/08u_fm2017_190234382_tmlcombo_live.jpg)

Editors’ Note: Because of their relationships with people on the crew of Pan American World Airways Flight 7, the authors have had an abiding interest in the mystery surrounding the crash. Ken Fortenberry’s father Bill was the navigator on the doomed flight, and Gregg Herken’s fourth grade teacher Marie McGrath, who for him was one of those teachers you always remember, was a flight attendant. Both Bill and Marie died in the accident.

Fortenberry, a veteran newspaper reporter and editor, and Herken, a history professor and former curator at the National Air and Space Museum, met through their mutual obsession with this tragic episode: “I was researching [Pan Am Flight 7] online when I kept running across Ken’s name,” Herken says. Herken visited Fortenberry in the latter’s North Carolina home, and the two began to work together to find the cause of the Pan Am Flight 7 crash. After working individually for decades and together for 13 years, they believe they have at last found the answer.

**********

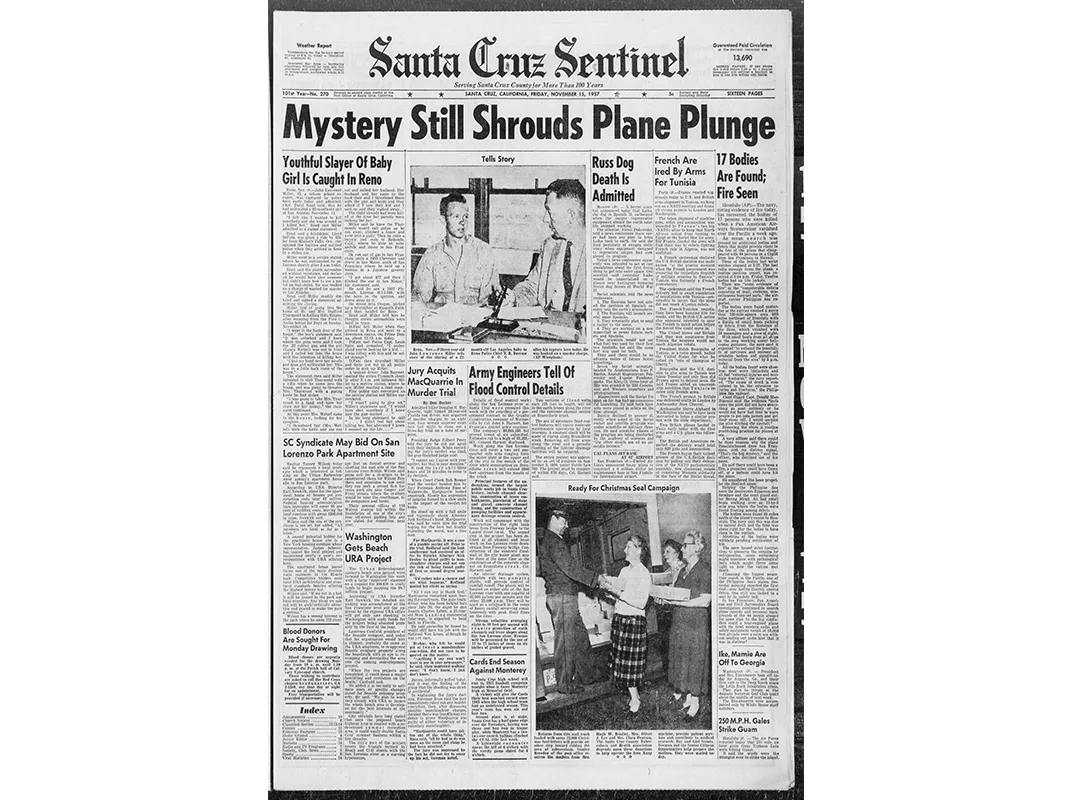

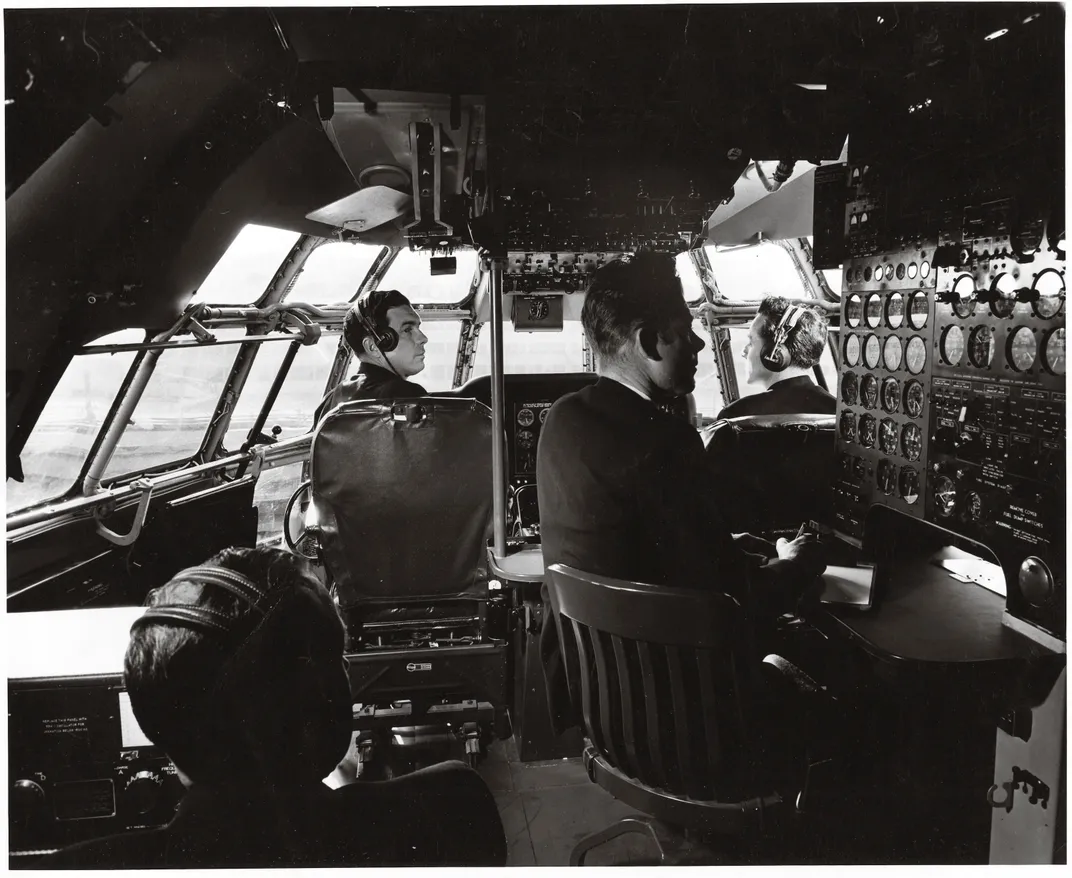

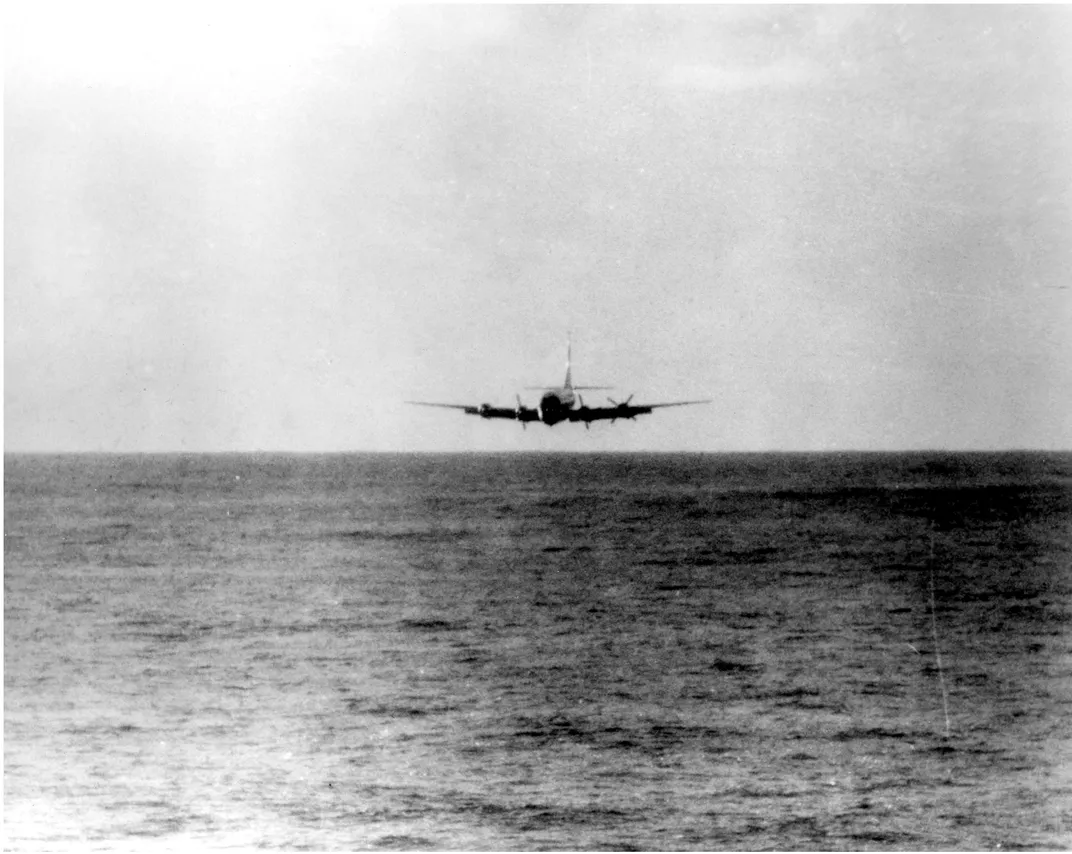

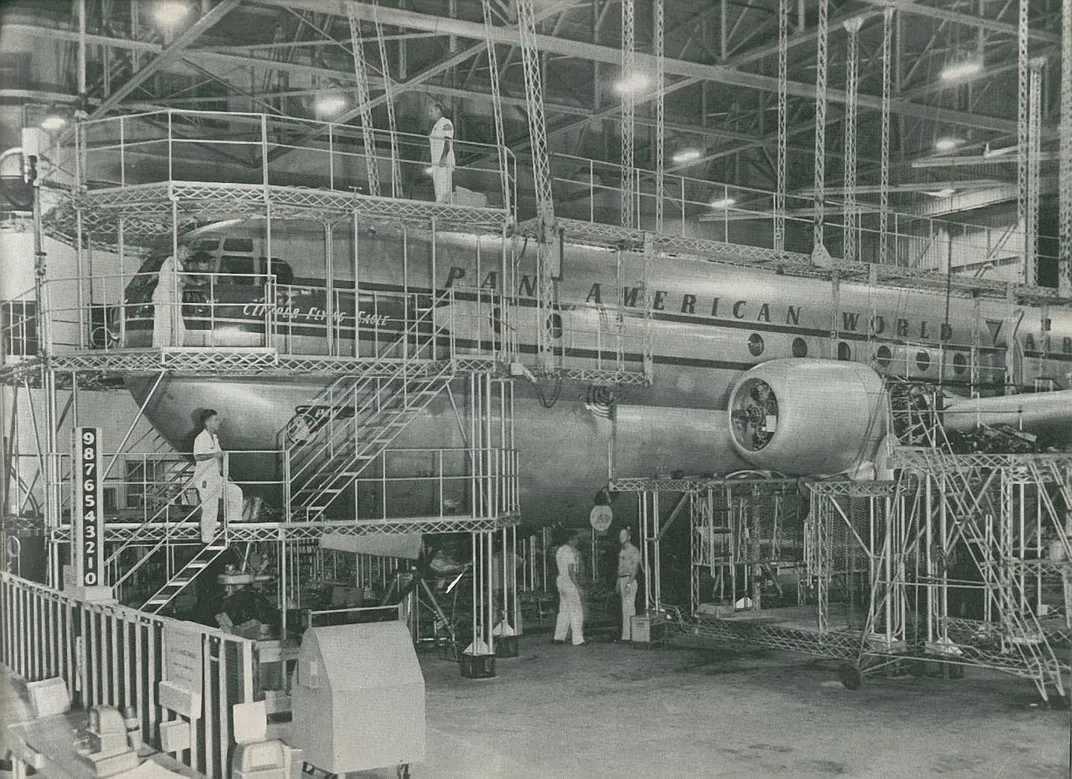

For almost 60 years, those of us connected to Pan American’s Flight 7 have had to accept the word of the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board: “insufficient tangible evidence at this time to determine the cause of the accident.” On November 8, 1957, PAA-944, Clipper Romance of the Skies vanished en route from San Francisco to Hawaii, the first leg of a round-the-world trip. The Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was a four-engine aircraft so big and luxurious it was called “the ocean liner of the sky.” On board were 38 passengers and six crew.

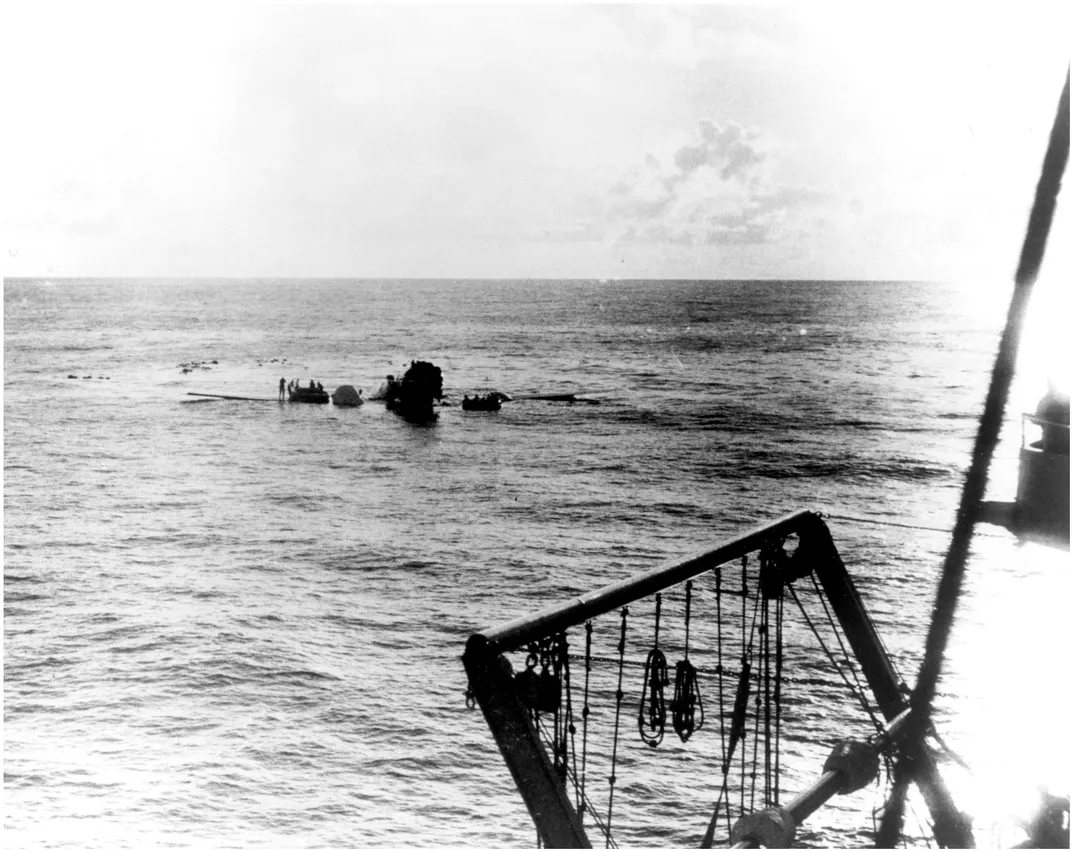

A few days after the airplane’s disappearance, floating debris and 19 bodies from PAA-944 were discovered in the Pacific Ocean. Several anomalies connected to the crash could not be explained: From the location of the wreckage, it appeared the Clipper had continued to fly for 23 minutes after its last routine position report, and the crew had sent no distress call. The aircraft had hit the water at high speed more than 90 miles north of its intended flight plan. Although there was no clear evidence of an onboard fire, several bodies, including the pilot’s, contained elevated levels of carbon monoxide.

As investigators probed, the mystery deepened. The purser on Romance of the Skies that day, Eugene Crosthwaite, had a grudge against the airline, and a few days earlier, had changed his will, leaving a copy in the glove box of the car he’d parked at the airport. A passenger on 944, William Harrison Payne, was a former Navy underwater demolitions expert, and shortly before the flight had purchased a one-way ticket to Hawaii and three insurance policies—including a policy that paid double in the event of accidental death. He’d claimed he was going to Hawaii to collect a debt. But the amount of money owed, according to family members, was less than the price of the one-way ticket, and no one in his family knew the name of the alleged debtors.

Pan Am suspected that Crosthwaite had brought down the airplane, but the FBI rebuffed the airline’s requests to investigate him. Meanwhile, the insurance company fingered Payne. The ex-Navy frogman had used dynamite to blow a hole in the road that crossed his property, which was being used as a short-cut by logging trucks. He’d also boasted to his neighbors that he knew how to make a bomb using two flashlight batteries and a length of wire.

Payne’s body was not among those recovered. A Pan American official conceded to the insurance investigator that it was possible Payne had never boarded the aircraft.

After an unusually lengthy investigation, the examiners from the Civil Aeronautics Board—the precursor to today’s National Transportation Safety Board—concluded they could not determine why Romance of the Skies had gone missing. Sensational newspaper accounts speculated that the Clipper had been hit by a meteor, or even shot down by a flying saucer. Eventually, public interest waned.

Ours did not.

As we noted in an earlier article for this magazine (“The Mystery of the Lost Clipper,” Oct./Nov. 2004), Pan Am employees who knew the crew of 944 told us of a tantalizing clue not mentioned by the CAB’s investigators: a tape recording said to contain a weak and garbled distress call, sent just after the airliner reached mid-Pacific—the point of no return.

In the days before cockpit voice recorders, radio transmissions between the cockpit crew and air traffic control were recorded by a company known as Aeronautical Radio Incorporated, or ARINC. The ARINC tapes of 944 became the missing piece we hoped would provide a solution. Using 21st century signals-processing technology, we believed we could decode the cryptic message that had eluded the CAB’s experts 50 years earlier. But at the time we were researching our 2004 Air & Space story, the Pan Am archives were still being processed and cataloged at the University of Miami. (The airline had gone out of business in 1991.) University archivists estimated that it would be three years before the papers became available to researchers.

In fact, it was not three years, but 10.

In 2014, courtesy of a grant from the Pan Am Historical Foundation, we spent three days at the company’s archives in Miami. In the sun-lit reading room of the University’s Special Collections library, we pored over cargo manifests, maintenance logs, and sworn testimonies. As we read, the final, terrifying minutes of the doomed Stratocruiser’s plunge to the sea nearly 60 years earlier came to life for us.

The transcript of the CAB hearings on the crash ran to 367 pages. While we did not find the missing ARINC tapes, we discovered the next best thing: an analysis of what was on the recordings, conducted after the hearings had closed. This was the overlooked evidence that we had been told about. But what we found was even more troubling: a tale of collusion, complicity, and cover-up in the government’s investigation of the tragedy.

The Hearings

The official CAB hearings into the crash of PAA-944 began the morning of January 15, 1958, in a packed conference room at San Francisco’s posh Sir Francis Drake Hotel. Over two days, five investigators from the CAB’s Bureau of Safety examined 90 exhibits, including personal effects salvaged from the wreck site. They questioned 19 witnesses, including maintenance personnel, cargo loaders, and other Pan Am employees. The bureau’s experts paid almost no attention to the possibility of sabotage, focusing instead on the likelihood of a mechanical failure.

Indeed, there was a long history of mechanical problems with the Stratocruisers, which were powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major engines, the largest piston engines ever used in commercial aircraft. The engine-propeller combination on the Strats was particularly vulnerable: Several B-377s had encountered trouble due to a runaway or “overspeeding” propeller, a potentially catastrophic situation in which the variable-pitch prop cannot be feathered, and centrifugal force wrenches the blades to the lowest pitch stop. The resulting drag makes the aircraft aerodynamically unstable.

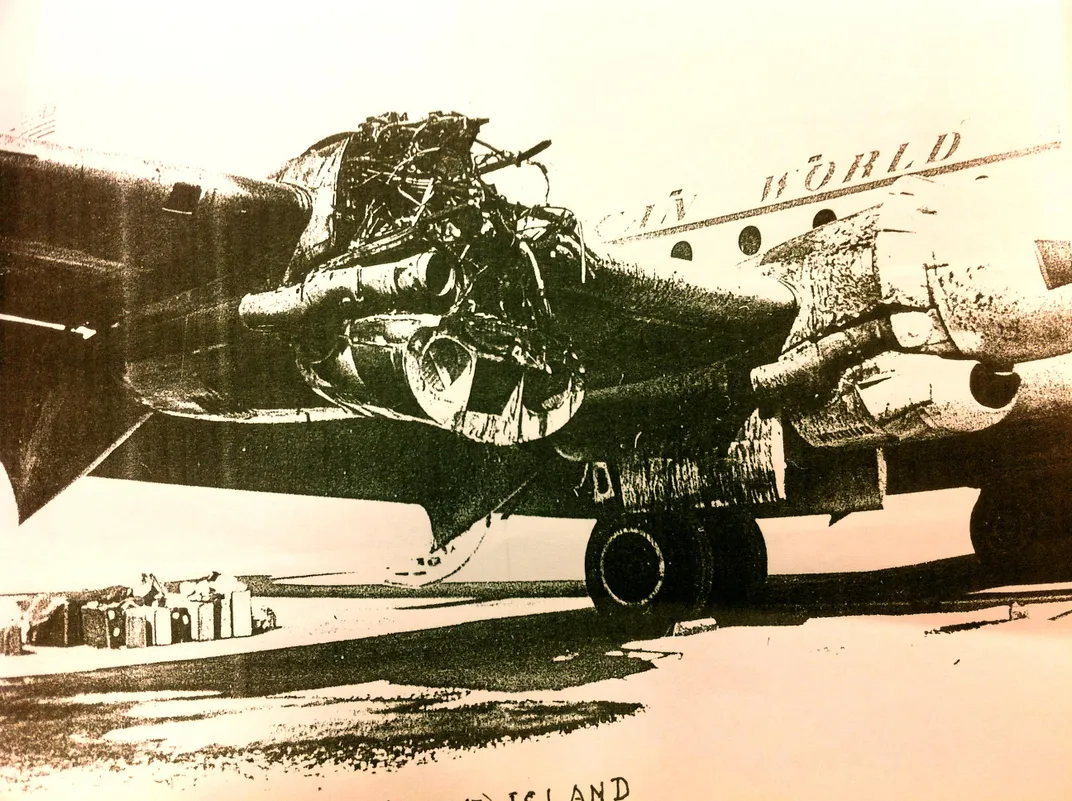

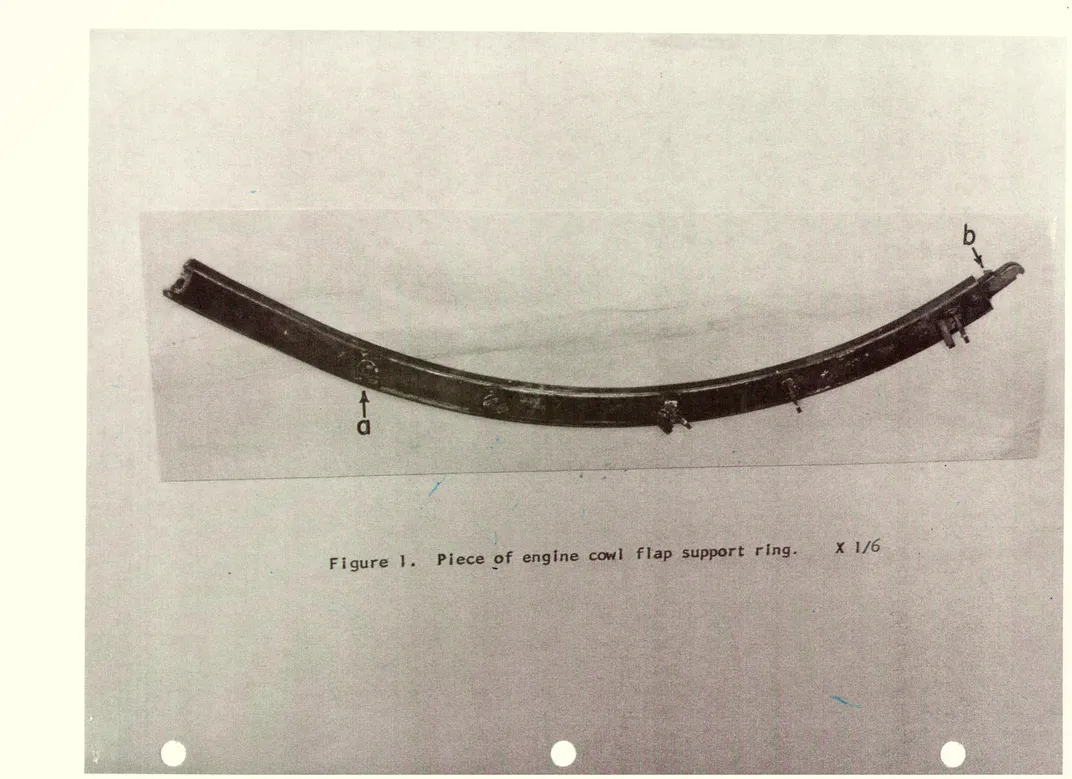

In 1952, an overspeeding propeller caused Pan Am Clipper Good Hope to shake itself to pieces over the Brazilian rain forest. An uncoupled overspeed—where a windmilling propeller breaks free of the shaft connecting it to the engine—was especially dangerous, since the prop could fly apart and pierce the fuselage, knocking out communications, injuring or killing passengers, starting a fire, or all of the above. One of the exhibits on display at the 944 hearings—a small section of an engine cowl ring, embedded in a scorched pillow found floating at the crash site—suggested just such an occurrence.

On the second day of the hearings, CAB investigators considered the possibility that the crew of 944 did send a distress call, but some unknown factor (a severed antenna, perhaps) had prevented it from being clearly heard. Radio transmissions made on the day of the crash had been recorded by ARINC receiving stations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle (the recording equipment at ARINC’s Honolulu station was out of order that day), and the board had collected the recordings and submitted them to audio experts at Bell Labs for analysis. Bell’s engineers were unable to find any message on the tapes, with one exception: 15 minutes after the Clipper’s last routine radio report, they heard a garbled transmission containing the words “four-four”—perhaps a reference to the airplane’s Pan Am designation, 944.

Independently, a group of Pan Am pilots who were personal friends of 944’s crew also listened to the tapes. They said the recordings did indeed contain a message, but the words were faint and either indecipherable or nonsensical. Ultimately, the pilots informed the CAB “that the majority of the words and phrases used in the message… are foreign to our radio telephone practices [and]…certain of the words are clearly not appropriate to the situation under investigation.” They deemed it “unlikely that the message as read in the report originated from [PAA-944].”

On January 16, 1958, the Bureau of Safety’s experts adjourned. More than 16 hours of testimony and hundreds of documents had produced no consensus on what had caused the crash. In their report, the CAB’s investigators expressed more certainty than the Pan Am pilots had on the question of a Mayday call from 944: “No radio message was received from the aircraft after the emergency situation began.”

Others at the hearings—including some of the CAB’s own experts—were not so sure.

On January 17, the day after the formal investigation concluded, audio engineers from the Dictaphone Corporation volunteered to give the ARINC recordings another try. After two weeks, using advanced equipment on loan from the Voice of America, Dictaphone claimed to have deciphered a weak transmission from Romance of the Skies, beginning approximately seven minutes and 30 seconds after the Clipper’s last position report. The annotated transcript that the company submitted to the CAB included not only a Mayday call but what seemed to be an urgent exchange among the crew, over an open microphone:

SO 292 Special Number and Flyer. [Also understood as “…number on fire.”]

Attention All Stations Pan American Air.

Verification Channel Bearing 11.

Still have one tank full. Am ditching flight.

CQ, CQ, Syracuse, New York.

J arm is missing, tail.

[Voice different than position report.]

Did you chart me? [Inaudible]… Special position.

[Same voice as position report.] Fuel control—3, 4, 5, 6,

Zero 2 fuel flow! Zero 2 fuel flow! Coordinate. [Two voices speaking excitedly.]What about 3 engine?

That question, the last thing on the tape, was heard clearly and confirmed independently by four listeners.

Evidence Withheld

The Dictaphone report—not sent to the CAB until April 8, 1958—cast the 944 investigation in an entirely new light. Or at least it should have. While some words or phrases were unintelligible—“J arm is missing, tail” for example—the distress call suggested that the cause of the crash was indeed mechanical, possibly an engine fire or explosion (“number on fire”), a problem with “fuel control” (“Still have one tank full… Zero 2 fuel flow!”), and, finally, trouble with the inboard engine on the right wing (“What about 3 engine?”). The Dictaphone discovery was tantalizing enough to persuade the CAB to send the ARINC tapes to additional audio experts for further analysis.

And here the crash investigation took a rather strange turn.

One of the most dramatic moments of the hearings had been the testimony of Phil Ice, president of the Transport Workers Union’s Local 505, whose members maintained Pan American’s fleet of aircraft in San Francisco. Ice bemoaned a “drastic curtailment of inspection personnel” by Pan Am, resulting in “dangerous deficiencies in inspection and maintenance.”

The airline’s real problem with the Stratocruisers was that they were too luxurious. During the nine-hour flight from the West Coast to Hawaii, first class passengers could stretch out in the roomy cabin, enjoy a drink in the airplane’s downstairs cocktail lounge, then sit down to a seven-course dinner. Travelers on overnight flights to Europe and Asia slept in Pullman-type berths. Pan Am was losing money on its Strats, and planned to replace them with faster, cheaper jets. Until then, the company had decided to economize by adopting some controversial maintenance shortcuts: having mechanics rather than their supervisors sign off on worksheets, for example, and running only every third engine and propeller on a test stand following an overhaul.

While Pan Am disputed Ice’s allegations, CAB inspectors took them seriously enough to pay an unannounced visit to the airline’s San Francisco maintenance shop after the hearings. They reported to their superiors: “Inspection and/or quality control in the engine overhaul is not adequate…. Maintenance practices are questionable.”

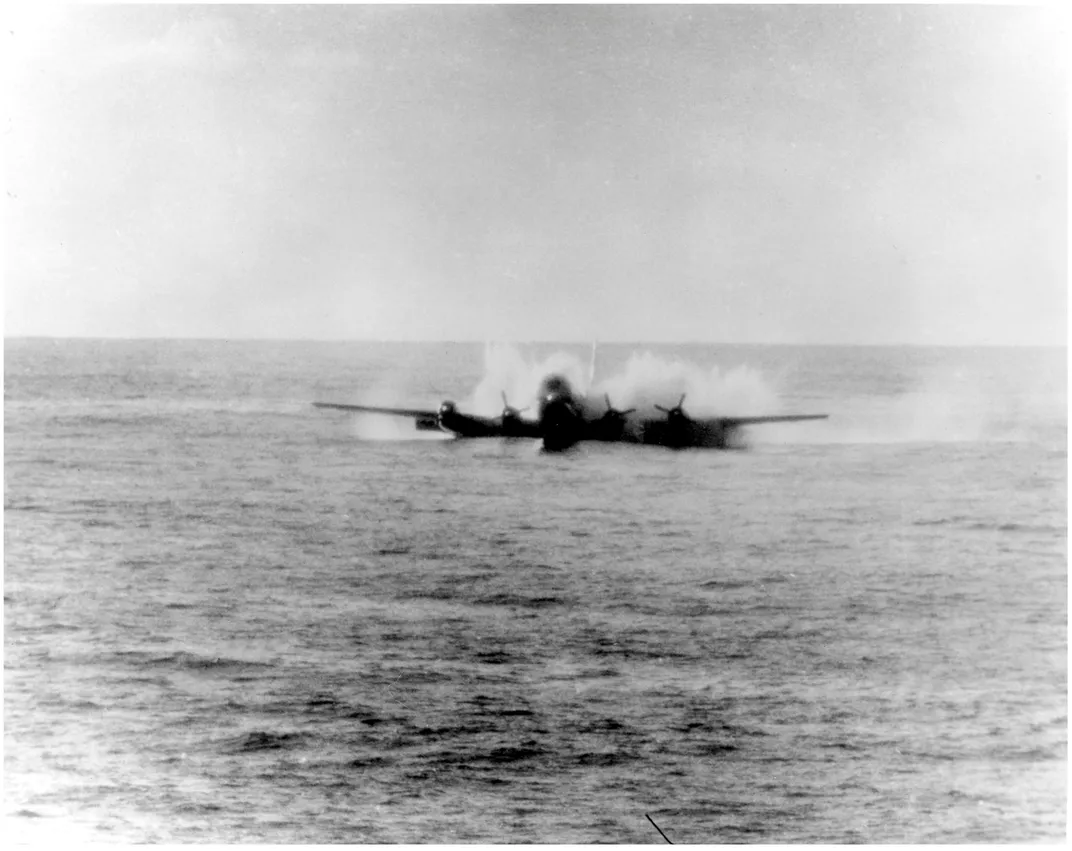

Even more alarmingly, the loss of 944 had not been an isolated incident. The airline that advertised itself as “the world’s most experienced” had recently suffered a series of Stratocruiser disasters. In a three-year period, three Pan Am B-377s had failed over the Pacific.

In 1955, the number 3 engine and propeller of Honolulu-bound Clipper United States had torn loose from the wing and fallen free, causing the aircraft to experience severe buffeting and an uncontrolled, descending turn to the right. Although the pilot eventually gained enough control to ditch the airplane off the coast of Oregon, two passengers and a pair of crew members died from exposure or drowning. The following year, 944’s sister ship, Clipper Sovereign of the Skies, PAA-943, had a propeller overspeed and subsequent engine failure, forcing the pilot to ditch in the Pacific. Although no lives had been lost, press accounts highlighted the big Boeings’ poor safety record. Influential journalist Drew Pearson used his nationally syndicated column to publicize these incidents, which seemed to confirm that Pan Am’s maintenance practices were derelict. Unknown to the public, the head of the Pan Am pilots union was threatening to ground the airline unless it replaced the trouble-prone propellers.

In the CAB’s hearings on PAA-944, the testimony related to the maintenance history of the airplane had been full of contradictions, inconsistencies, and even outright misrepresentations. One witness testified that Romance of the Skies had never experienced an overspeeding propeller, but others said that on June 4, 1957, five months before its fatal flight, the Clipper had survived a narrow brush with disaster. PAA-944 had taken off from San Francisco and was bound for Hawaii when an accelerating scream signaled a runaway propeller on number 3 engine. Although Captain Clancy Mead was able to turn the crippled airplane around, the drag from the unfeathered prop caused 944 to lose altitude. Mead recalled that on the way back to San Francisco, he had cleared the hills by no more than 500 feet before landing safely at the airport. (“It was a memorable evening,” he told us in a 2003 interview.)

The maintenance logs entered into evidence at the hearings told another troubling tale: In the weeks before the crash, 944’s engines had experienced a “constant fluctuation” in oil pressure, leaks from the turbochargers, and persistent cooling problems.

In May 1958, J.J. Cantwell, an attorney representing Pan Am, wrote to CAB official Robert Chrisp to protest Chrisp’s plan to cite Pan Am’s lax maintenance in the government’s report. In a separate letter to the airline’s legal department, Cantwell frankly admitted that he hoped to persuade Chrisp “to withhold the maintenance report from the public record.”

Pressure was building for a final resolution of the case. The underwriting company that had insured Payne, the ex-Navy demolitions expert, initially refused to pay his widow’s claim, pointing out that Payne’s body had not been recovered, and no witness had actually seen Payne board the airplane. (Tellingly, the FBI kept its file on PAA-944 open for several years after the crash. Following a rash of insurance-related aircraft bombings in the late 1950s, the bureau even listed Payne as a possible suspect in one, noting that it was “attempting to determine whether William Harrison Payne is still alive.”) Nonetheless, when Payne’s widow threatened to sue, the insurance company capitulated. At the time, audio analysis of the ARINC tapes by experts—including those at an unnamed “government agency”—continued. The Army pathologist who conducted the autopsies on 944’s victims refused to accept the CAB’s conclusion that the excess carbon monoxide found in some of the bodies had come from natural decomposition rather than from a fire or explosion prior to the crash.

Contents Under Pressure

By October 1958—nearly a year after 944 went down—Oscar Bakke, the director of the Bureau of Safety, informed his superiors that “because of the unusually large number of requests for the report [on 944] from the public, the next of kin, and from Members of Congress... further delay cannot be tolerated.”

Two months later, the government released its final report on the loss of Romance of the Skies. While the CAB conceded that it was “entirely possible” the crew had sent a distress call, “the Board could not definitely establish that any emergency transmissions came from Clipper 944.” Also unexplained was the mystery surrounding the carbon monoxide in some bodies. Although the CAB report acknowledged the board had found a “number of irregularities in maintenance procedures and/or practices” at the airline, the absence of a clear distress call and the dearth of physical evidence from the crash made it “obviously impossible to associate [those irregularities] with, or disassociate them from, the accident.” The report makes no mention of Phil Ice’s allegations of poor maintenance.

Nor would readers find any acknowledgment that within the bureau, the report’s conclusions had been hotly debated. We discovered the discord among its authors during a search of the board’s records at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Those documents showed that three weeks before the report’s release, the head of the Civil Aeronautics Board, James Durfee, dissented from the conclusions reached at the Bureau of Safety meeting that had approved the final report. “I am not satisfied with the language, the discussion, or the findings with respect to Pan Am’s maintenance practices,” he wrote. Durfee also noted that the CAB’s parent organization, the Civil Aeronautics Authority, had yet to reprimand Pan Am for its maintenance deficiencies—or to ensure “the deficiencies have been corrected.”

Durfee knew the CAA had a built-in conflict of interest: The agency responsible for investigating commercial aviation accidents was also charged with promoting flying to the public. CAA and CAB officials, including members of the Bureau of Safety, were routinely given free tickets by the major carriers, and were wined and dined by the companies they were supposed to be overseeing. (One mechanic at the 944 hearings testified that he’d overheard a CAB investigator and a Pan Am executive discussing where to go to dinner that night, and what time to play golf the next morning.) The CAA was subsequently abolished and replaced by the Federal Aviation Agency (later the Federal Aviation Administration), which had responsibility for investigating aircraft accidents, not for promoting air travel.

Durfee finally swallowed his misgivings and approved the draft CAB report. He even added a comment, one presumably requested by Pan Am and its attorney: “Irregularities of maintenance practices and/or procedures disclosed during the investigation could not be linked to the accident.”

The government never fully investigated the role that shoddy maintenance may have played in the loss of PAA-944. Nor did the CAB conclude that the cause was catastrophic mechanical failure, despite the evidence of the Dictaphone transcript.

Unsatisfied with those findings, we conducted an investigation of our own.

Our research showed that statistically, the B-377 was half as safe, per passenger-mile flown, as other aircraft used on the same routes by rival airlines at the time—United’s Douglas DC-6s and TWA’s Lockheed Constellations. Of the 56 B-377s built, 10 were lost in accidents. In five of those cases, the crash occurred after a propeller failed, causing that engine to be torn from the wing. The CAB’s account of one near-crash—the engine separation on PAA-947, Clipper Queen of the Pacific, in 1953—bears an eerie resemblance to what we believe may have happened on PAA-944: Following the loss of number 4 engine, PAA-947 “went out of control in a right descending turn accompanied by violent buffeting.” When the engine separated from the aircraft, the top portion of the cowl ring mount broke off and struck, but did not penetrate, the fuselage.

As we have reported, investigators at 944’s crash site collected the top section of an engine cowl ring, embedded in a scorched pillow. Four years earlier, the pilot of Queen of the Pacific had regained control of his Stratocruiser—after dropping 7,000 feet—by dumping fuel from the right wing tank.

Assuming an engine separation occurred on Romance of the Skies, did Captain Gordon Brown dump fuel before his attempted ditching? The burned items recovered from the debris field suggest that there was still plenty of fuel on board when 944 hit the water—and we think we know why. When 944 experienced overspeed in the June 1957 incident, Captain Clancy Mead had just begun a fuel dump when his flight engineer warned that the vapor streaming from the wings had caught fire. (Mead later suspected what the engineer saw was moonlight glinting off the fuel droplets.) Accordingly, Captain Brown may have feared that dumping fuel would start a fire on the aircraft. So the Stratocruiser, still heavily loaded, hit the ocean in a shallow dive at high speed—the conclusion of the CAB’s experts, based on the type and location on the aircraft of the recovered parts.

So is the mystery of the Lost Clipper finally solved? Unless robotic technology advances to the point where we can search the seabed for the remains of Romance—or evidence is found that proves William Payne was still alive after November 8, 1957—questions about the tragedy will persist. But our discovery of the transcript of 944’s Mayday call, and the cowl ring fragment, point to the conclusion that Romance of the Skies had crashed because of a catastrophic mechanical failure, not a bomb.

Ultimately, what brought down Romance of the Skies was human fallibility. A propulsion technology had reached its limits. A government agency had become cozy with the companies it was meant to police. And an airline, in its rush to enter the Jet Age, had decided to cut corners, ignoring the risk to passengers and crew.