In 1914, Photographing the Panama Canal From the Air Could Get You Arrested

How a sensational article about the defense of the Canal got its author, photographer, and editor in hot water.

:focal(3524x2046:3525x2047)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/61/8d6174dc-481d-4230-8e3f-316170244850/36k_dj2020_canal191x4a24805u_live.jpg)

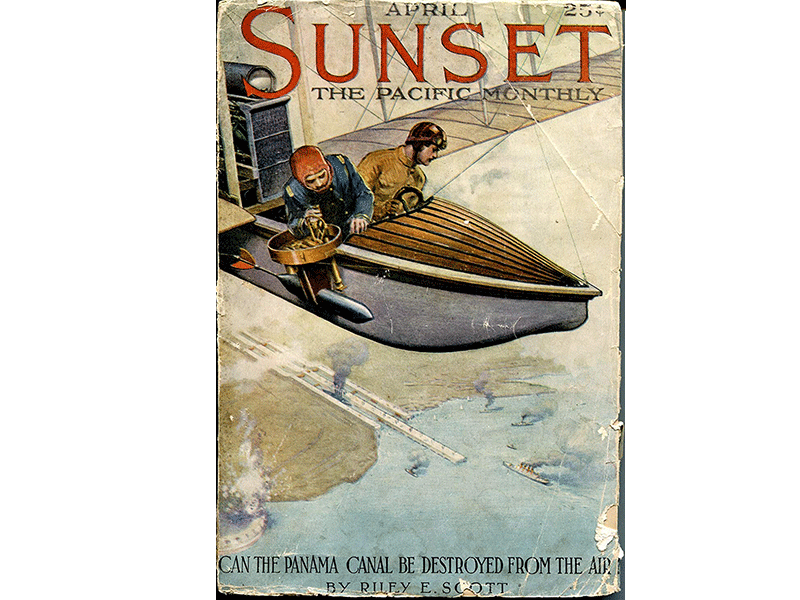

When the Panama Canal was nearly completed, in April 1914, Sunset magazine editor Charles Kellogg Field jeopardized the future of his magazine—and his personal liberty—by publishing photographs and a story about the canal’s military defenses. The article’s title alone ignited a national firestorm: Can the Panama Canal be destroyed from the air?

Three months later, John W. Preston, United States Attorney for the Northern District of California, at the War Department’s request, charged Field and three other men with spying: pilot Robert G. Fowler; Riley E. Scott, West Point graduate turned bomb-dropping expert; and Ray Duhem, San Francisco aerial movie-maker.

An 1895 graduate of Stanford University’s pioneer class, Field had built a successful career as a San Francisco insurance agent. But in 1908, his passion for journalism led him to join the Sunset staff full-time.

Field had been a Sunset contributor for years, although most of his submissions had been poetry or general commentaries on contemporary events. But the writer had also developed an interest in aviation and the increase of airship and airplane activities in California.

Although now known primarily as a lifestyle magazine, in its earliest days, Sunset often covered military activities that affected the western United States, including the Spanish-American War, the rebellion in the newly acquired Philippine Islands, and the increasing naval presence on the West Coast.

Field became Sunset’s editor-in-chief in 1914, and his opinions began to have an impact across the country. That same year, Field decided he would join with other aviation supporters to convince Congress that airplanes were more useful—and more dangerous—than believed.

Looking for other challenges, Fowler considered crossing the Panama isthmus; if successful, he would become the first to fly from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic.

When he decided to attempt the Panama crossing, Fowler designed a new aircraft with aeronautical engineer Jay Gage. The aircraft had wheels plus outriggers and pontoons and an 80-horsepower engine from Berkeley, California-based Hall-Scott.

Fowler’s proposed route followed the nearly complete Panama Canal, then crossed the soon-to-be-filled Gatun Lake, the engineering heart of what made the continental crossing possible for ships.

Knowing only the distance to be traveled, an uninformed observer might consider Fowler’s flight a casual undertaking: only 52 miles from takeoff in Panama Bay on the Pacific Coast to the Bay of Colon and Cristobal on the Atlantic shore—one hour and 30 minutes flying time. It was actually extraordinarily dangerous. Fowler would be forced down in the shallow waters at Cristobal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/6e/f36ebcf1-7075-462f-986c-bbecbb17c940/infamous-photo.jpg)

Field decided to publish the story along with Duhem’s pictures. In a foreword to Scott’s article, he pointed out “[A]lmost directly under the aeroplane can be seen the emplacement for the most powerful weapon ever constructed, the first 16-inch disappearing gun, which has an effective range of about twelve miles.” He noted in the introduction that an airplane carrying 500 or more pounds of explosives—instead of a camera—could easily eliminate such a gun. Field’s introduction continued, “Colonel Goethals [who supervised the construction of the U.S. Panama Canal] is reported as saying in February: ‘The Canal fortifications are entirely adequate and I do not think there is the slightest danger of the Canal being captured by any enemy.’ The great canal builder might have added, in a paraphrase of Paul Revere: ‘None, if by land, and none, if by sea.’ But how, if by air? [Riley Scott] believes that the United States, having fortified the Canal against attack by land and sea, must eventually protect it from attack by an aerial foe.”

The provocative cover and article caught the attention of the U.S. War and State Departments—and eventually President Woodrow Wilson.

Brigadier General E.H. Crowder, the U.S. Army’s Judge Advocate General, read Scott’s article and sent the issue of Sunset to U.S. Attorney General James C. McReynolds in Washington with a recommendation that some action be taken.

In late June, McReynolds ordered San Francisco-based attorney John W. Preston to issue arrest warrants for the four men.

All were charged as spies under the provisions of the Defense Secrets Act of 1911 for disclosing information regarding national defenses. The penalty, if convicted, was 10 years’ imprisonment should a foreign power be the recipient of the information, or a one-year imprisonment and a fine of $10,000 if the disclosure was made inside the United States.

On July 10, 1914, federal marshals arrested the men and took them before U.S. Commissioner Francis Krull at his office in the Post Office Building at the corner of Seventh and Mission streets in San Francisco. After their arraignment, Krull followed the recommendation of Preston and released the group on their own recognizance until 9:30 a.m. the next day.

The four men, especially Fowler and Duhem, were astonished by the charges. In 1911, Duhem’s movie company had made a film about the progress of Panama Canal construction that he released to theaters on January 1, 1912. The movie had been well received.

Fowler and Duhem had followed established procedure. The 1911 Act required that permissions be granted for any photos or entry into a restricted military area. And permission was granted prior to the flight by the chief engineer of the Isthmian Canal Commission, Colonel George W. Goethals.

Fowler and Duhem described their meeting with Goethals to Krull and to the press. District Attorney Preston took note, but said that considering the gravity of offenses, “I think this case has merit. It has always been an Army regulation with the force of law forbidding the taking [of] photographs or views of the permanent work-of-defence, whether course of construction is completed.”

Fowler and Duhem declared that they had no intention of violating any law; Field noted that the sole publication purpose was to “stimulate interest in a larger appropriation for aerial defense in the United States.”

At the July 11 preliminary hearing, Fowler and Duhem offered a formal statement: “Col. Goethals not only gave his permission, but he wished us the best of luck, and said he hoped the pictures would turn out well.” Field’s defense noted that the photograph in Sunset showed no actual fortifications or artillery but only the emplacement for a gun and the preliminary work for a fort.

At the hearing, U.S. Commissioner Krull set a trial date for August 10, 1914. It never happened. Initially a postponement allowed the government time to review a new point of law. U.S. statutes prohibited the taking of photographs of military installations, but the legal language clearly stipulated terrestrial photos.

Prior to the Fowler-Duhem flight, it had never been considered that the taking of photographs of a land-based object might not apply when taken from the air. President Wilson and Congress soon remedied this oversight.

On December 26, 1914, U.S. Attorney Preston received notice from Attorney General McReynolds that Scott had been given permission to travel to Europe for the U.S. War Department for the purpose of “learning for the United States War Department all he can of the methods of aviation fighting.”

Before Scott returned, a grand jury intervened, considered the facts of the proposed case, and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to continue. Federal officials agreed.

In 1938, on the 25th anniversary of the flight, Fowler made a second Panama Canal crossing—this time as a passenger in a Pan American Airways transport. The flight was escorted by six Army bombers and three Navy patrol planes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/c0/41c07214-4c5a-4a58-a96b-67fca58cd3f9/charles-field.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/80/f680fea3-3fdd-49d2-a249-85d8526798cc/36f_dj2020_fowlerafterflight_live.jpg)