The First Black Airmen to Fly Across America

They took off with $25 and a dream.

:focal(2942x828:2943x829)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/61/dc61d372-46e2-4bd5-9b46-42bc3130ea22/05b_fm2018_si-99-15420_live.jpg)

On an early June night at Woodlands High School in Hartsdale, New York, the cafeteria is jammed. A noisy crowd of at least 200 has shown up. They’re here to see a play called Fly With Banning.

A Louis Armstrong melody fills the big room, and the crowd falls quiet. Over the music a voice sings sweetly, “Taking to the sky. Taking to the sky,” over and over. An actor in a black leather coat with sheepskin trim, a fabric helmet, and aviation goggles steps in front of the crowd.

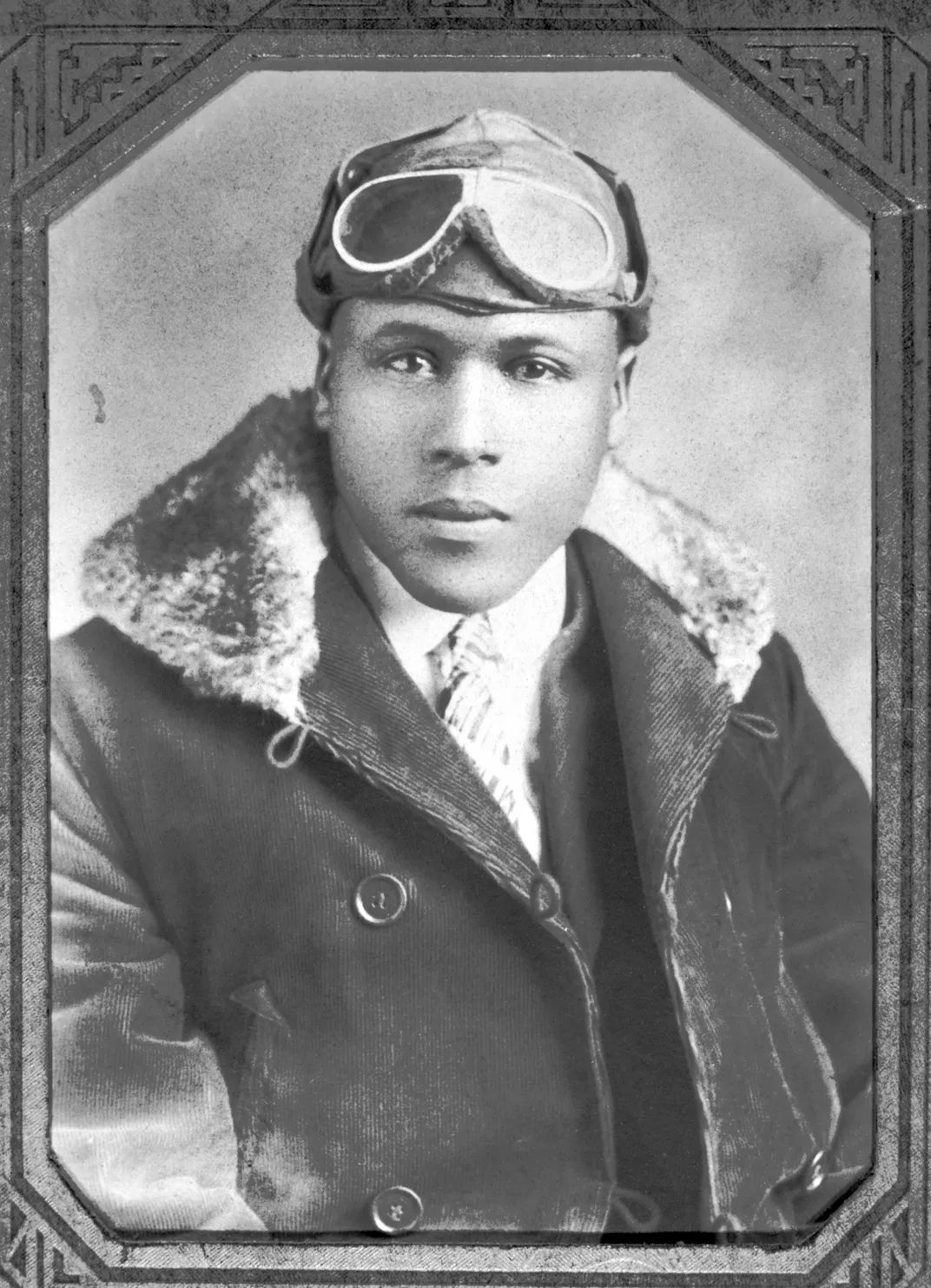

His name, he tells the audience, is James Herman Banning. It is 1932. He discovered his love for flying as a child and never let go of his dream. When no flight school in the country would admit a “colored” man, he found a white pilot willing to teach him, and in 1926, he became one of the first black pilots in America. Now, he tells the audience, he is about to do something no Negro has ever done before. He will fly an airplane “clear across the United States of America,” from Los Angeles to New York City.

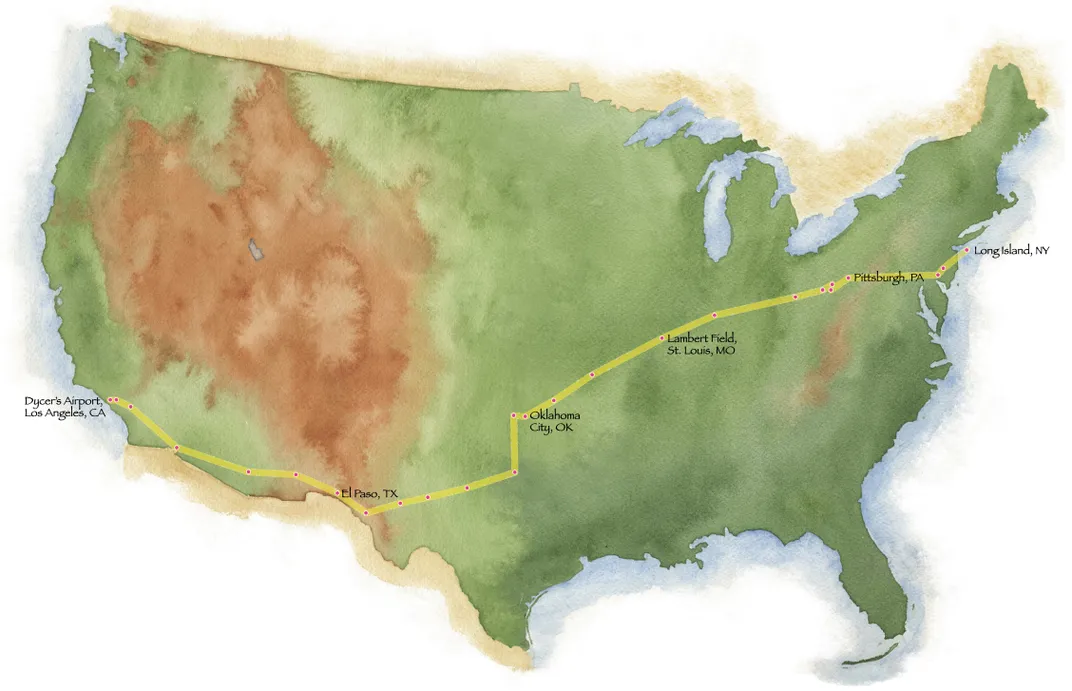

When the real Banning took off from Los Angeles’ Dycer Airport on September 19, 1932, just four people came out to watch, a small turnout for the start of an epic flight. As the orange and black Alexander Eaglerock biplane circled wide over the city and then nosed eastward, people on the ground very likely questioned whether the two aviators—James Banning and Thomas Allen—would make it over the looming mountains, let alone reach their destination, 3,000 miles away. Their chances appeared slim.

In an unpublished manuscript written by Thomas Allen and held in the Oklahoma Historical Society’s collection, Allen would later write that “this crate acted like it did not care whether it flew or not.” The two aviators had plenty of other reasons to worry. The Eaglerock featured a sputtering, 14-year-old Curtiss OXX-6 engine, and was badly underpowered; according to Banning (who later wrote a series of newspaper articles about the flight), the Eaglerock was “put together [with] various cracked-up airplane parts.” The instruments were also unreliable, including a compass that was off by 30 degrees. Their biggest worry, though, wasn’t the airworthiness of their crate. Although their final destination was a continent away, they’d taken off with just $25 between them. When they landed in Yuma, Arizona, their first major stop, they would be out of money. Allen, however, had a plan to keep them going: Everyone who contributed money, meals, or the like would be invited to sign the lower left wingtip of the aircraft. Allen called the wing “The Gold Book.”

The play performed in Hartsdale was written by white educator and author Louisa Jaggar, inspired by her multiracial grandson to create works about African-American role models. Hers is not the first effort to bring the story of Banning and Allen to a larger audience. In 1987, Philip Hart, a great-nephew of Banning, together with his wife Tanya, a television and radio personality, produced and directed a documentary titled Flyers in Search of a Dream, on the history of black aviation. Now 73 and living in Los Angeles, Hart recalls growing up in Denver in the 1940s and seeing family photo albums with pictures of Banning and Allen. His grandmother was Banning’s older sister. She, his aunt, and his mother told him about the flight. He recalls, “My grandmother was a couple of years older than her brother. She worried about his safety, she told me, but trusted his instincts.” Hart recalls “showing family photos of Banning and his airplane to teachers, and they didn’t necessarily believe it [had happened].” As a junior high school student, he went to the library to learn more about his great-uncle. He found, he says, “a tremendous amount about Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post, and nothing about Banning. Why couldn’t I read about him?” While working as a real estate developer and University of Massachusetts professor of sociology, he gathered historic documents, photographs, film, and other materials about early black aviators. He has since written a number of books for young readers and reading-challenged students about black aviation pioneers. He and his wife are also developing a feature film about Banning and Allen’s flight, which they hope to have in theaters in 2019.

Aviation pioneering apparently circulates in the Hart family blood. “My love of airplanes started from early childhood,” says Christopher, Philip’s younger brother by three years. “My mother once told me that the first picture she ever saw me draw was an airplane. But I didn’t learn of Banning’s achievement until I was in high school, when I became aware that Phil was exploring it.” Christopher is a licensed pilot with commercial, multi-engine, and instrument ratings and a noted transportation safety expert who has served two terms on the five-member National Transportation Safety Board. In 2015, he became the first African-American appointed chairman of the NTSB, completing his two-year term in March 2017. He remains an NTSB member. “James Herman Banning’s achievements led to my being where I am today,” he says. “He played a major role in starting the process of getting African-Americans more involved in aviation.”

**********

Banning and Allen had separately made their ways to Los Angeles at the invitation of William Powell. In 1929, Powell established the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, named for the late pioneering African-American stunt pilot. He developed a variety of programs to train blacks for employment in the region’s burgeoning aviation industry, and asked Banning to serve as the school’s chief pilot. In 1931, Powell staged the country’s first All-Negro Air Show. Fifteen thousand paying spectators turned out to watch the festive Colored Air Circus put on by the Five Blackbirds, African-American stunt fliers. That event’s success convinced Powell that aviation spectacle could help drum up interest in flying among African-Americans.

In 1932, when a rumor spread of a $1,000 prize for the first black fliers to complete a transcontinental flight, Powell and copilot Irvin Wells set out, but crashed in the mountains of New Mexico. Shortly after, Banning and Allen decided to make an attempt, with no fanfare, hoping to become the first African-Americans to make the flight. Flying across the country was first accomplished some 20 years earlier by Calbraith Perry Rodgers and had been repeated four times since.

Allen had originally considered making the flight solo; as he would later write, he was skeptical of some black pilots’ claims: “I was fed up [with] Negro aviators,” he wrote. “Most of their flying was done in the newspapers and very little on wings.” Instead, he headed for Los Angeles, apparently meeting Banning for the first time just four days before the two left on their transcontinental adventure.

As the Eaglerock took off, Allen plotted their route: They would zigzag from Los Angeles southwest through Arizona and across to Texas, then veer northeast into Oklahoma and through the Midwest, and finally turn due east toward their final destination, outside New York City. The flight plan took them through towns where the pilots knew someone. Allen would write in his manuscript, “I planned not to get any person or group of people in one town to give more money than just enough to put us into another town where we were known. I also told Banning we did not intend to pay for a night’s lodging on the way, but might have to pay for some of our meals.” In the depths of the Great Depression, that was asking a great deal of people who were often too poor to feed their own families. But the two men had no alternative; they would have to rely on the support of segregated black communities that lay along the course Allen had mapped. Allen said, according to William Powell’s 1934 book Black Wings, “Gee, we’ll be just like hobos, begging our way.”

Banning was inspired by the thought: “We’ll capitalize on our plight. We’ll call ourselves the ‘Flying Hobos.’ ” They decided not to christen their airplane with some catchy name or even alert the press, recalled Banning, fearing they might “make announcements and then fall down.” If they succeeded, he later told the Chicago Defender, they would “then let others herald it.”

As the Eaglerock headed toward Yuma, Arizona, Allen recalled, “It got so hot that I took off my overalls and unbuttoned my shirt. The water was boiling in the radiator and the slip stream from the propeller was blowing it through a hole in the cowling.” When the fliers reached Yuma, the airport attendant recognized Banning: “Aren’t you the same fellow who landed here two years ago and blew a tire?” Banning said he was. The man remembered that Banning made a three-point landing before he hit a pothole in the runway, damaging the airplane. The airport replaced the runway with a modern asphalt strip. “Your accident is the cause of us having a real airport now,” the man said.

Banning wasn’t shy: “That should be worth at least a tank of gasoline.” Soon, they were flying on to Tucson. They flew through the dusk, “from one beacon light to the next,” wrote Allen, landing just after dark.

Early the next day, as they prepared to take off, Allen noticed gas dripping from the carburetor. After fixing a leaky float, they flew into the already fierce desert heat. On a northerly heading, they flew low through the Apache Pass, then descended toward El Paso. Their fuel nearly gone, they set down in southwest New Mexico. They were broke and stuck in Lordsburg, a town where they knew nobody.

The population was mostly “Mexicans and Indians,” said Allen in a 1982 oral history conducted by Phil Hart, “and when we told them that we were trying to make a transcontinental flight, they said ‘We don’t care what Negroes are doing, we are having a hard enough time eating.’ ”

Desperate for a few gallons of gas to get them along to better pickings, Allen pawned a flying suit and his watch for $10 to a member of the community named Mr. R.C. Hightower. He then invited Mrs. Hightower to sign the Gold Book; she “was thrilled to have her name fly all the way to New York,” wrote Allen.

They flew by dead reckoning; in the high desert, thin air kept them close to the ground (“never more than two hundred feet from the top of the sagebrush,” wrote Allen) in their underpowered airplane. The engine was rated at 100 horsepower but, Banning joked, “Some of the horses are dead.” West of El Paso the Eaglerock faced its first major test: crossing over the 8,000-foot El Capitan, which rose up like a watch tower at the southern terminus of an enormous limestone castle wall. There was no way to fly around the range and still have enough gas to reach El Paso. Suddenly a squall brewed up in front of them. They had no choice but to head straight into the dark clouds. Driving rain battered them. Banning strained for a view of El Capitan’s rocky top. “Engulfed, flying blind,” Banning wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier. “We can’t see our own wing tips,” let alone the ground. Terrified, he realized too late, “We are fools to fly through this without proper equipment.”

His heart pounding, he thought, “A stall or spin here would be fatal!” They gradually descended until they finally found better visibility and, to their relief, not a rocky face to crash into.

Once on the ground in El Paso, they had to face their next hurdle. They were almost 1,000 miles into their journey and broke again. They sent a telegram to a friend in California, asking for $25.

Plotting a course toward Dallas, they flew along the railroad tracks between towns, sometimes landing in farm fields where farmers went slack-jawed at the sight of two black men descending from the sky. After the farmers got over their shock, they sometimes invited the men home for a meal. Banning and Allen managed to charm a few into siphoning gas from their tractors to speed them on their way.

After overnighting in the tiny west Texas oil patch town of Wink, they hopscotched to Wichita Falls, Texas, a town where Banning’s wife had relatives. When they landed at the airfield there shortly before dark, a local newspaper reporter happened to be on hand. The pair spent the night with Banning’s in-laws. When they returned to the airport the next morning, Allen said in his oral history, they were stunned to find that close to 1,000 people had gathered on the field. The local newspaper had run a story about their transcontinental project. Making their way through the crowd, they confessed to being broke. “Let’s give them a little help!” somebody called out. In a few minutes Banning and Allen were climbing back into their cockpits $125 richer.

They flew into Oklahoma, where both men had family. They stopped in El Reno, where Banning visited his brother; Allen reunited with his mother in Oklahoma City. The next day, the two began knocking on doors, asking people to help them achieve their personal goal and advance the race and an entire nation. Amazingly, people with barely enough to feed themselves took up collections. Families offered beds and meals. Signatures began to cover the doped canvas.

Word of their attempt to fly across the country made it to the black press, and radio stations and newspapers issued reports on their progress. Learning of Banning and Allen’s approach, people began to watch for their arrival.

When they landed in Tulsa, William Skelly, a wealthy white oilman, was waiting at the city airport. Though not a pilot, he owned a small airplane factory and flight school and had put together the syndicate that built the city airport. He offered to fund the two all the way to St. Louis. They stopped in Carthage, Missouri, then pushed on.

**********

Learning more about the flight and the struggles the aviators encountered, Jaggar and her research partner, Pat Smith, decided to pursue a multimedia project about the aviators’ lives, including an exhibit, a website, videos, and the play. They found actors for the roles of Banning and Allen, and raised funds to bring the play to schools and libraries in underserved communities. They reached out to aviation historians, including Von Hardesty, who co-curated the National Air and Space Museum’s seminal 1982 exhibit, “Black Wings: The American Black in Aviation,” and co-wrote an accompanying book with the same title.

Racial segregation “created a parallel world of flying,” notes Hardesty, “[resulting in] all-black flying clubs, airshows, and training programs. The main task for early black aviation pioneers was to break out of this pattern of segregation. One highly visible [way] was to establish new air records.”

Thousands of people were on hand in St. Louis to greet the Flying Hobos. One newspaper reported on their attempt at the transcontinental journey in the depths of the Great Depression: “What will come of this flight and this record remains to be seen. But it is certainly stimulating that we have heroes who come to light in this very worst of times.”

In St. Louis, though, the men realized their airplane’s overtaxed engine needed to be rebuilt. They did not have the money to buy the parts for it. Both men knew people in town, though, including a teacher at a trade school, who said that the school could completely rebuild the engine. The students soon had the OXX-6 running.

The two flew to Springfield, Illinois, on to Terre Haute, Indiana, and then, after a few days’ rest in Columbus, Ohio, they took off confident they could reach their goal. Within a few minutes, though, the engine began shaking so hard they thought the whole aircraft might fall apart. They had to set down. They were flying over rolling farmland and patchy forest. All Banning could see were “Trees, bushes, stumps!” He glided down, managing to pull the nose up enough to get over a fence before side-slipping into a rough landing on a plowed field.

Banning and Allen inspected their aircraft. “Not a scratch on the ship,” remarked a proud Banning. “You don’t die every time your motor does,” he noted later on. They were somewhere outside the town of Cambridge, Ohio. Allen spent the night beneath the wing while Banning made his way back to Columbus. Once there, he found an airplane parts supplier who told him to take whatever he needed, on the house.

“We [are] still flying,” the delighted Allen remarked. But the closer they got to their endpoint, New York, the more anxious they grew. They flew with the gnawing fear, said Allen, of “getting within a few miles of our destination and absolutely run[ning] out of the last drop of gasoline.”

Then came what he called “one of the greatest stops…of the whole flight.”

When Banning and Allen landed in Pittsburgh, they telephoned the offices of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the country’s leading black newspapers. Courier publisher Robert L. Vann drove out to the airport and brought the pair downtown, where they were heralded like conquering heroes. Election Day was approaching, so Vann took them to meet state Democratic Party officials in town. Seeing a chance to exploit the young men’s fame and airplane, party officials enlisted them to publicize Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidential campaign during their flight east over Pennsylvania. In return for dropping handbills supporting the Democratic ticket and writing first-person stories about their cross-country adventures, Vann and the Democratic Party promised to cover the men’s remaining expenses, handle publicity for them, and pay to put the Eaglerock back in shape for a return flight to California.

They took off with gunny sacks filled with some 15,000 leaflets. “We were more than happy to throw them out of the plane to save weight,” Allen recalled in his oral history. They watched as the papers fluttered down and “just about completely littered Pennsylvania.”

They flew to Bala Cynwyd, outside Philadelphia, then to West Trenton for their last night on the road. Around eight in the crisp and sunny fall morning of October 9, they cranked the OXX-6 engine one final time. “Old Sol seems to be smiling on our success,” Banning thought. A little over an hour later, the two aviators circled the towers of Manhattan. Not long after, they looked down upon what Banning called “the biggest thrill of our trip—our goal…. I feel like looping the loop!” he exclaimed.

**********

Christopher Hart hopes that Banning’s accomplishments “will continue inspiring people to be more accepting of the concept of African-Americans in significant positions in the aviation industry. My hope is that informing people about Banning’s will and determination will inspire people to have a similar will and determination no matter how daunting the challenge.”

After the play ended that June night at Woodlands High School, I approached A.J. Shikapwashya, a bright-eyed 11-year-old sixth grader from a nearby middle school, whose parents are immigrants from Zambia. He tells me that he hopes to become a veterinarian. “It was very inspiring how they achieved their dream,” he says. “They didn’t have the money to do it, but they did it anyway. I’d like to learn more about them.”

**********

The 3,300-mile flight lasted just 41 hours and 37 minutes but had taken 21 days to complete—not much of an improvement on the first cross-country flight, two decades earlier. But little matter. African-American pilots had crossed the continent in the air, beyond the reach of race, outside the bounds of discrimination, over the barriers of segregation.