Bring the Fallen Airmen Home

A volunteer group helps fund searches for the missing by selling rides in the types of aircraft they once flew.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/eb/b8eb69fc-f7d9-488d-aec8-b79fad6b2d40/dosti_mark_kent_over_creater_live.jpg)

On a cold day in April 2012, a team of historians, archaeologists, surveyors, forensic technicians, and police stood on a hillside near Allmuthen, Belgium. One of the team members was a handler for Buster, a Labrador retriever trained to detect the scent of cadavers. A U.S. Army Air Forces B-26 had crashed on the hill 68 years ago, and the team had begun excavating the site in the hope that Buster could detect the remains of the World War II bomber’s airmen.

The Department of Defense estimates that 79,000 U.S. personnel who served during World War II remain missing today. “Everybody flies MIA flags, but hardly anyone knows or appreciates these numbers,” says Mark Noah, who led the team working at Allmuthen. Today, despite advances in casualty accounting, unanswered questions still torment many families of MIAs. Their predicament has a name—“ambiguous loss”—and the grief can linger across generations. As one widow expressed it: “No, missing isn’t dead. It’s worse than dead.”

Noah, who flies Boeing 767s as a captain for UPS, also operates History Flight, a nonprofit foundation based in Marathon, Florida, that is committed to finding missing U.S. service members. To help underwrite its research activities as well as raise awareness of its mission, History Flight offers paid rides aboard three restored aircraft: a North American B-25H Mitchell medium bomber, a North American AT-6 Texan advanced trainer, and an N2S Stearman primary trainer.

Since 2003, History Flight volunteers and consultants have joined forces with other volunteer groups and coordinated with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) to locate lost servicemen. History Flight has spent over $2 million, most of it from private donors, to find and document the remains of American MIAs. The idea, says Noah, “took root as we worked on the vintage planes. We were restoring aircraft when we should really be recovering the missing crews. We started by just investigating air crashes, but now we look for GIs too.”

Noah has assembled a diverse team. There is Agamemnon Gus Pantel, an expert in pre-Columbian archaeology who lives in Puerto Rico. Kent Schneider is a retired U.S. Forest Service geologist. Paul Schwimmer is a land surveyor and former U.S. Army reservist who self-describes as “driven.” “My office is the field,” he says. “My real skill is finding things, and I’m good at it.”

Perhaps the most intriguing contributors are the interspecies collaboration of Paul Dostie and Buster. Dostie, a retired California law enforcement officer, adopted Buster as a puppy. (His wife insisted, he says.) Buster, now 11, has a robust sense of smell, developed initially for recovery missions after avalanches and refined through successive experience in detecting different forms of human remains: soft tissue, blood, bones, cremation ashes, and bone decomposition after 50-plus years. For History Flight expeditions, Buster travels in airliner passenger cabins; on overseas trips, he is accompanied by a veterinarian.

Because the foundation’s focus is on locating men who fought in all theaters of World War II, its reach is global. Trips to European countries—France, Belgium, and Germany—are balanced by earlier and ongoing missions to remote Pacific locales with memory-evoking names like Palau, Tarawa, and Truk. During a trip to Mili Atoll in the Marshall Islands in 2007, “we really went off the grid,” says Noah. “We flew Air Marshall Islands to a former Japanese airstrip, camped in a beachfront grass hut, and returned by fishing boat. The entire island was just interlocking bomb craters with pieces from hundreds of Japanese aircraft everywhere. We found a B-25 intact on the lagoon floor, plus the wreck of an A-24 Banshee, the Army Air Forces version of the SBD Dauntless.”

History Flight’s visit to the hillside in Allmuthen had its origins in 1990s research by German aviation historians Horst Weber and Manfred Klein. The two were trying to learn more about the loss of 10 Martin B-26 Marauders from the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 397th Bombardment Group during a December 23, 1944 attack on a railroad bridge near Eller, Germany.

Weber and Klein eventually found nine of the 10 crash sites, one of which was in Allmuthen, Belgium. Fieldwork determined that the Allmuthen crash site contained the wreckage of the forward fuselage of the B-26 Bank Nite Betty (the tail section likely fell nearby).

The crash site for Hunconscious, another 397th B-26 reported lost over Belgium, remained a mystery—as did the fate of its six-man crew.

While working in a spruce plantation near the Bank Nite Betty site in the fall of 2006, a German forester affiliated with the Air War History Working Group Rhine-Moselle (another volunteer entity) found an impact crater and a leather fragment from what turned out to be the collar of an American B-3 flying jacket. The fragment bore a laundry mark, H-7489. Such marks incorporate flight crew service numbers, but H-7489 matched no one on Bank Nite Betty’s roster. Records showed instead that it belonged to Sergeant Eric M. Honeyman (service no. 39037489), a crewman on Hunconscious.

But the promising lead never gained traction. When representatives of the Rhine-Moselle group uncovered two long bone fragments, they alerted U.S. Army Memorial Affairs Activity–Europe, whose representatives took possession of the bones and referred the case to DPAA. Though two DPAA historians who visited the site in early 2007 concluded there was enough evidence “to warrant further investigation,” interest flagged, other projects intervened, and years passed.

DPAA, based in Hawaii, spearheads the mission to account for U.S. MIAs. The agency operates globally, and its approximately 400 military and civilian personnel are stretched thin. According to Johnie E. Webb Jr., DPAA’s deputy to the commander for legislative affairs and external relations, DPAA is limited to dispatching 10 interdisciplinary teams of 10 to 14 military personnel and civilian specialists at any one time. Considering DPAA’s resource constraints and formidable recovery goals, prioritizing which airplane crash sites to investigate is challenging. Says Noah: “Ninety-five percent of [DPAA] resources go to Vietnam MIA recovery, which is just five percent of the problem.”

Noah’s interest in the Hunconscious MIAs was partially triggered by reading The Dead of Winter, a 2005 book by Bill Warnock. A U.S. Air Force veteran who served in Germany, Warnock co-founded the 99th Division MIA Project to search for 99th Infantry Division MIAs from the Battle of the Bulge. The Dead of Winter details how Division veterans and their families teamed with forensic scientists and amateur historians to recover the remains of 12 fallen comrades. The 99th MIA Project seemed a likely European partner for History Flight, so Noah reached out to Warnock.

Warnock in turn introduced Noah to two World War II historians, Jean-Louis Seel and Jean-Philippe Speder, both Belgian army veterans. Seel, now a railroad stationmaster, and Speder, a water treatment electro-mechanic, had collaborated since their school days by scouring World War II battlefields within driving distance of their homes. They were instrumental in recovering all of the 12 99th Infantry Division MIAs and knew the region well.

In May 2011, ahead of a June reconnaissance trip to Belgium, the History Flight team, joined by Seel, Speder, and Warnock, convened at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, to research a dozen potential cases, including Hunconscious. “I call it ‘micro-history’—connecting with veterans groups, and then going through archives,” says Noah. “This collective research yielded after-action reports, deceased personnel files, squadron diaries, missing air crew reports, and aircraft-in-distress reports.”

History Flight’s two weeks of on-site reconnoitering in June revealed that the debris field discovered five years before by the German forester had since been clear-cut and was now overgrown with vegetation. The impact crater was clogged with 10 to 12 feet of logging detritus and five feet of standing water. Still, the site held promise, and they decided to return.

After History Flight’s departure, Seel and Speder continued working the Allmuthen site throughout the summer. Careful visual inspection soon yielded more artifacts, including an E6B “whiz wheel,” a circular slide rule, complete with leather case.

When the History Flight crew returned to Allmuthen the following April, their new objective was to determine if human remains from Hunconscious were present. Speder and Seel were on site for the expedition, and they were impressed by History Flight’s search protocols. It was Speder’s first collaboration with on-site archaeologists. “Searching infantry sites is different than air crash sites,” he says. Once an infantry site is finally identified, “you don’t have to search that widely for remains.” Air crash remains, Seel and Speder soon learned, could be extensively scattered and fragmented.

The team’s first step was to sweep the entire site with hand-held metal detectors. Then Buster was let loose to begin his scent-detection work. The debris field, sprinkled by fallout from the detonation of one or more of the bombs carried by Hunconscious, proved extensive, nearly a fifth of a square mile. Paul Schwimmer, History Flight’s land surveyor, laid out a survey grid so that the locations of any findings could be precisely documented. Next, a backhoe cleared vines, nettles, and crater debris.

The investigation was accomplished in the harsh weather for which the Ardennes region is known. “We encountered rain, fog, ice pellets, and snow,” says Noah. “The guys wet-screening the debris wore heavy-duty rain gear. I thought wearing a leather bomber jacket would do, but I ended up contracting pneumonia.”

The team did its most labor-intensive work in four promising patches of ground. The third patch was the spot where the laundry mark fragment had been found, but field workers felt greater anticipation in searching the fourth patch: the impact crater made by the wreckage of Hunconscious. To enable excavation of the crater, drainage ditches were built to empty it of water. Once the crater was dry, Buster alerted numerous times on its center. (The dog signals his detection of a target scent by lying down and barking.)

Prolonged and methodical archaeological digging and sifting can be trying, especially when weather conditions are awful or results nil. Schwimmer recalls being part of a team searching Palau for the remains of B-24 airmen. “Stress and frustration nearly caused my brain to flip,” he says.

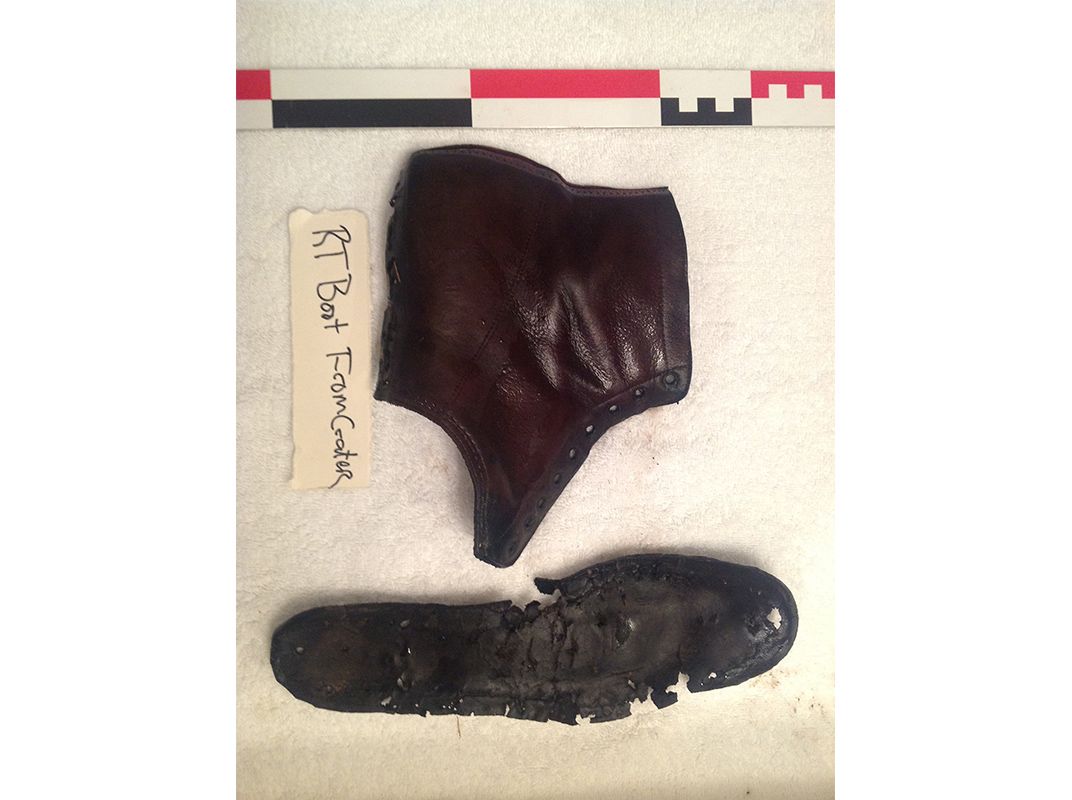

At Allmuthen, though, neither impatience nor frustration interfered with History Flight’s work. After the impact crater was drained, the archaeologists found U.S. Army Air Forces boots and boot fragments. The first 10 inches of excavation yielded something even more compelling: a bone fragment subsequently identified as part of a human right tibia. It was enough to signal a halt to the excavation. In a gesture of cooperation, Noah pulled out his cellphone to call DPAA’s Johnie Webb in Hawaii.

Noah’s once-contentious relationship with DPAA has become mutually productive. “[DPAA] once saw History Flight as intrusive, bothersome, and antagonistic,” says Gus Pantel. “They now realize we’re a bona fide, genuine effort.”

“Mark has gone beyond what many other groups do in terms of research, analysis, and fieldwork,” says DPAA’s Webb. “He has people with expertise in various disciplines. They’re well-rounded, and Mark has come to realize the difficulties [DPAA faces].”

Within days, DPAA representatives arrived at Allmuthen.

After History Flight departed for other case recovery sites, several DPAA teams worked the Allmuthen hill for more than 100 days, from late May until mid-September. Webb assessed the overall effort as “very productive. Remains were scattered over a very large area.”

In fact, site work was particularly successful. In July 2014, DPAA confirmed the identification of remains for all six Hunconscious crewmen and notified their families. Remains for pilot First Lieutenant William Cook and crewman Staff Sergeant Maurice J. Fevold were buried with full military honors that year. Burial ceremonies for the remains of three more—Honeyman, Arthur LeFavre, and Ward Swalwel—were scheduled for Arlington National Cemetery last August.

Seel and Speder assisted two of the DPAA teams during that eventful summer. “The impression that followed me was the extent of the destruction,” says Speder. “Every bit of that B-26 was torn, ripped, twisted or bent.”

Three hundred yards from the Allmuthen impact crater, Seel unearthed a portion of a flak helmet sometimes worn above the leather flying helmet during combat. The helmet fragment had been bent and had in turn squeezed a portion of leather helmet. Inside were two pieces of human skull. “When you came across such items,” says Speder, “where death had been frozen in time, you are overwhelmed by a feeling of deep humility and respect.”

History Flight continues its search for World War II’s missing. They’ve led numerous expeditions to Europe in the last three years. And since 2013, in a massive ongoing excavation project on the Pacific atoll of Tarawa, the team has recovered the remains of at least 120 U.S. Marines.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David31_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David31_copy.jpg)