Brooklyn’s Jewel

A National Park Service project reclaims aviation history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Brooklyns_Jewel_FALSH.jpg)

Linc Hallowell remembers driving past Floyd Bennett Field, New York City’s first municipal airport, as a young boy on his way to Rockaway Beach in the late 1960s. Back then, the field was an active U.S. Navy base, and it sparked his interest in aviation history. “I just thought, That is so cool,” says Hallowell, 46. “Seeing the aircraft got me started building model airplanes and then researching the aircraft and getting their stories. But it was an active air station, so you couldn’t go in.”

Ten years ago, Hallowell, a ranger with the National Park Service, got the opportunity to transfer from Ellis Island to the Gateway National Recreation Area, a group of historic sites in New York Harbor that includes Floyd Bennett Field. He leapt at it. “Now I’ve got the run of the place,” he says, pointing out that Gateway’s attractions range from the natural (pristine beaches and a wildlife refuge) to the human histories of a Colonial-era lighthouse and a 19th century military fort. The problem, however, is that the human element at Floyd Bennett Field—its hangars and terminal building, dating to 1931—has been left to crumble. Finally, though, after fits and starts, a period-faithful restoration of the now-down-at-the-heels terminal building has begun.

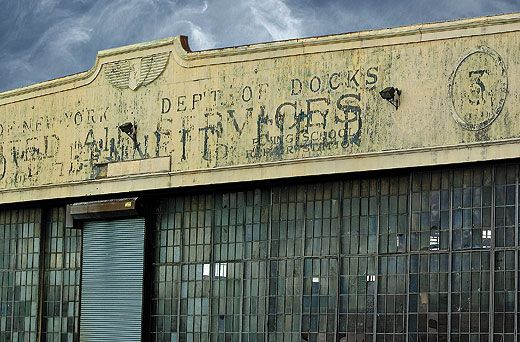

The restoration has been in the works since 2007, when Anthony Weiner, a U.S. representative from New York’s 9th district, secured a $4.8 million grant to pay for the renovation of the terminal, now known as the Ryan Visitors’ Center. Hallowell has long pined for the restoration, lamenting daily the state of the red-brick, municipal-style building with Art Deco fixtures and flourishes, some of which are still in place. Patches of elaborate stencil work are faintly visible beneath layers of paint. But now, with a new roof completed, the various building permits affixed to the front doors, and the building evacuated of park employees, Hallowell believes the transformation is finally under way. Urban archeologists hired by the park service have begun to chip away the paint to determine the original colors. “It’s not like redoing the kitchen at your mom’s house,” says Hallowell.

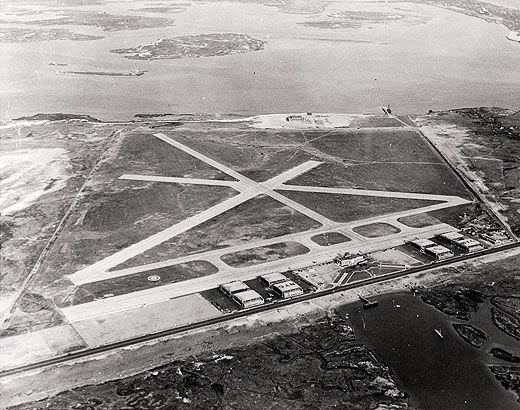

Floyd Bennett Field was named after the pilot who flew American explorer Richard E. Byrd on an attempted trip to the North Pole in 1926 in a Fokker F-VII. The field’s nine buildings—most of them hangars, all but one in disrepair—were dedicated in 1931 beneath a flyover by hundreds of airplanes, which the New York Times described as “soaring like a swarm of insects over the sea.” During the next eight years, pilots chose the field as the departure point or destination for dozens of record-setting speed and distance flights. Its location along the eastern seaboard made it a good jumping-off point for transatlantic and transcontinental adventures. Aviators such as Jimmy Doolittle, Jacqueline Cochran, and Howard Hughes were attracted by the airport’s long, paved runways—ideal for takeoffs by fuel-laden aircraft.

Inside the terminal building, Hallowell points out the amenities available when air travel was a more luxurious experience: A newsstand, a lounge for passengers and pilots, a restaurant with French doors, a telephone room, a barbershop, a Western Union office, a press room, and a stained-glass ceiling. All will be restored.

The work will be done in stages, says Gateway unit coordinator Dave Taft, who is overseeing the project. Besides the roof, the first phase will consist mainly of restoring and reopening the ground floor of the terminal, which will be stocked with kid-friendly exhibits with lots of interactive, moving parts (these have the added benefit of being less costly to maintain than electronic exhibits). Taft estimates that the building will be open to visitors by next summer at the latest. During the second phase, the basement and upstairs wings of the building will be restored and used as office and meeting space for park employees. After that, the park hopes to restore a tile-lined underground tunnel, which once served as a passage between the terminal and outdoor boarding area to keep passengers from wandering into the path of taxiing airplanes. The tunnel resembles a New York City subway station. Finally, the control tower will get a makeover.

Hallowell has contributed to the project by conducting archival research. Crucial have been the archives of Rudy Arnold, Floyd Bennett Field’s resident photographer, many of whose photographs will hang in the terminal. “This was the center of the aviation universe for about 10 years,” says Hallowell. “Every time you go through a news archive, you find something you didn’t know. There’s a great picture of Wiley Post, Amelia Earhart, and Laura Ingalls in the restaurant, sitting there eating lunch. There they were, eating soup in a room I’m in and out of every single day.”

Some of the buildings at Floyd Bennett have their own ecosystems. “If you neglect the structures, they will go back to the natural,” says Taft. “Birds will nest in the cracks. But they really knew how to build things back then. The runways are three feet thick with concrete.”

Taft is quick to point out that as a commercial airport, Floyd Bennett Field was not successful. Newark Airport in New Jersey was—and still is—more accessible from Manhattan, and as such got more commercial aviation business. “Floyd Bennett was an airfield in the middle of nowhere,” says Taft. “The nowhere just grew up around it.”

In 1941, the field was granted to the federal government for wartime use, and it remained an active naval air station until 1971, when it was brought into the Gateway fold. The restoration, however, will focus on the airfield’s municipal era. “We have a pretty compelling aviation history,” says Hallowell, “but if you think of aviation sites within the park service, you’re going to think of the Wright brothers, Kitty Hawk, and Dayton aviation. Unless you are an aviation history buff, Floyd Bennett is probably not going to be on the top of your list. So we’re really looking forward to being able to have this terminal building where somebody like me can say, ‘Hey, come on in. Let me tell you the story of the field.’ ”

After listening to a briefing from a park ranger in a lovingly restored terminal building, visitors can walk out to the tarmac and see things much as they were in the 1930s—the field surrounded by wetlands, no skyline in sight. The only things that could possibly disrupt the reverie are the low-flying jumbo jets on their approach to John F. Kennedy International Airport and a nagging anxiety about the traffic that awaits on the Belt Parkway, heading back to the city.

David Shaftel, a writer from New York City, is now stationed in Mumbai, India, as a correspondent for the New Delhi-based Tehelka group of publications.