For a few magical years, it looked like every family would own an airplane.

Buy Your Plane at Penney’s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Buy-Your-Plane-at-Penneys-631.jpg)

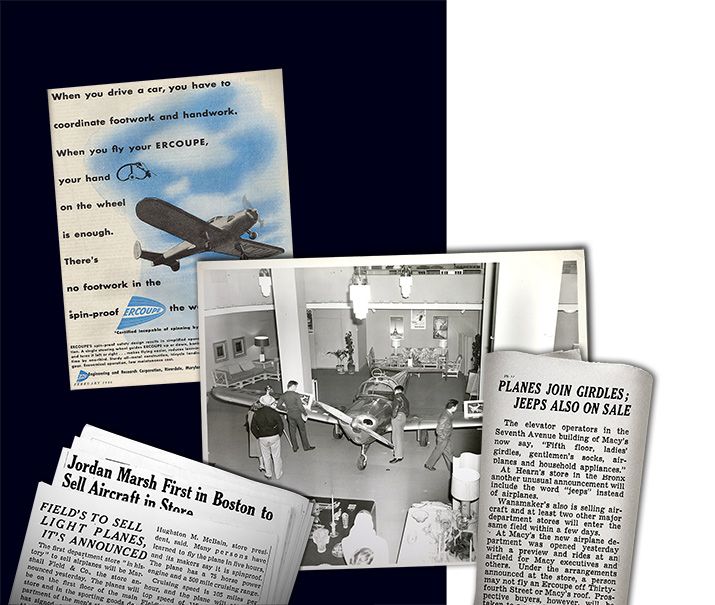

When Macy’s department store opened its doors one October morning in 1945, its customers were treated to a vision of the future. In the center of a showroom display called “The Flight Deck” sat a gleaming ERCO Ercoupe airplane, resting on a patch of artificial turf. Salesmen Alec LaJole and Harold Chaplin were waiting. The two men were pilots, recently finished with military service, and ready to welcome their customers to the world of aviation, with conveniences that were arrayed around the airplane. There was a quasi-simulator that featured an Ercoupe cabin and windshield, through which one could see color footage of the view from the air and overhear conversations between the pilot, passenger, and air traffic controllers. There was a model “Esso Airpark,” a futuristic residential airport that featured hangars, airplanes, showrooms, runways, service stations, and working beacon lights.

Crowds were drawn to Macy’s new offering by a full-page ad in the September 26 New York Times, which read “Macy’s makes news again! Within less than two months after V-J Day, you will be able to walk into Macy’s and buy—an airplane! And not only a plane, an Ercoupe… Macy’s chose Ercoupe for you [b]ecause it’s safe; and as easy to handle as your family car.”

With the crowds came journalists, from national magazines to local newspapers. Earle Griffith was an eager early customer, a 1945 article in the New York Post reported. Considering the travel time from his farm in Massachusetts, he said, “It takes me four and one-half hours to commute by train. With this baby I could make it in an hour and one half.” Elmer Ruark, a postal worker from Salisbury, Maryland, was more cautious. He told the salesmen he was just looking, but mentioned to his wife that with the post office’s flat roof available for landings and takeoffs, he “sure could use one of them [Ercoupes].” One Marine sergeant tried to trip Chaplin up, possibly thinking a mere showroom salesman wouldn’t understand how the Ercoupe could be spin-proof. But Chaplin, a veteran of 32 combat missions who came to Macy’s “via Saipan in a B-29,” calmly showed off the Ercoupe’s leading edge spoilers, which helped the airplane avoid the dreaded spin.

The salesmen had a mission, summed up in a published essay by R.E. “Duke” Iden of the aircraft manufacturer Taylorcraft: “In every successful sale, he is doing more than merely selling a plane or making a little cash for himself; he is helping build a better world, he is adding another man or woman to the growing army of air travelers; he is a missionary spreading a gospel for the progress of civilization.” The department store airplane was a bold experiment in retail: an exuberant leap into the postwar world, with private aviation leading the way. In a department store, anybody could check out the airplane as easily as he might try on a shirt.

Department stores all over the country dove into the market. At Bamberger’s in Newark, New Jersey, elevator operators hollered, “Sixth floor, airplanes!” Farmer J.W. Geer was one of the first to make a down payment, purchasing an Ercoupe as a surprise for his son, due home at any moment from duty with the Eighth Air Force. So did two mothers from Newark, each buying one for her military pilot son. Ernest Hawkins, an East Coast salesman for an Illinois company, bought one for his regular commute to the Midwest.

Over-the-counter airplane shoppers even had a small variety from which to choose. Piper Aircraft signed up with Mandel’s in Chicago and Wanamaker’s in New York, and had one-, two-, and three-seater models, retailing from around $1,000 to $3,000.

A major enticement was that getting your new airplane out of the store and into the air didn’t take much. A customer buying an Ercoupe at Macy’s, for example, paid a $998 deposit and put the balance on the store’s “Cash-Time” payment plan. Then arrangements were made for delivery of the airplane to a nearby airport. There, the customer got his first flying lesson from a contracted instructor, who would coach him through to the first solo. This is where the Ercoupe could sell itself: It actually performed as advertised.

Doyle Getter was a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal who in August 1945 made his way out to the Anderson Air Activities facilities at Malden Air Base, Missouri. Waiting for him was Gwen Landry, who gave him a quick ground tour of an Ercoupe. “In less than an hour I was flying, taking off and landing unassisted: [Landry] just sat beside me,” Getter wrote. “After three hours and 50 minutes of instruction, I soloed. ‘Just me and the birds,’ I thought to myself, up there so soon all alone. But it was a grand feeling. And a new world had opened up, a thrilling, exciting world, and the transition had come swiftly and easily. It was even simpler, it seemed, than learning to drive a car.”

The new retail flying experience—placing an order in the store, then taking delivery and soloing at the airport—was carefully developed well before the war ended, and in the Ercoupe’s case, brought together three brilliant pioneers of modern civilian aviation: Fred Weick, the designer; Henry Berliner, the manufacturer; and Oliver Parks, the salesman.

Weick, who was the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ authority on propellers, met Berliner at Langley Field in 1926, where they collaborated on a NACA project to improve propellers for the U.S. Navy airship USS Akron. Berliner, who founded his own airplane company that year, had been experimenting with balsa wood rotors in his helicopter flights at College Park, Maryland. The Berliner Aircraft Company was one of the first to adopt NACA’s cowling—a metal shroud that cooled the radial engine and reduced drag—an award-winning project Weick had led.

As an extracurricular project with his NACA colleagues in the mid-1930s, Weick developed the Ercoupe’s direct ancestor, the W-1. The wing was mounted high on the fuselage and had its propeller on the rear to push, rather than at the front to pull. The W-1 had two seats, steerable landing gear, and simplified controls, and it was nearly impossible to stall. Soon after Weick’s innovations with the W-1 proved successful, Berliner enticed his friend to partner with his new Engineering and Research Company—ERCO. With the goal of a safe, easy-to-fly, consumer-friendly aircraft, Weick built upon the W-1’s innovations, and the Ercoupe was born. The first production model rolled off the line in 1938, with a prized designation from the Civil Aeronautics Administration (the Federal Aviation Administration’s predecessor). The agency decreed the Ercoupe “characteristically incapable of spinning.” Just over 100 airplanes were sold before World War II halted production, and Berliner converted ERCO to work for the war effort.

Oliver Parks was an entire industry on his own. He started off selling candy bars, then moved on to Chevrolets. In 1926, he learned to fly. The following year, a few months after Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic success, and wary after his own close calls in the air, he entered the flight instruction business, opening Parks Air College in St. Louis, which was selected during World War II as one of eight civilian schools to help train Army Air Forces pilots. When the program was phased out in 1944, Parks—now a recognized authority not just on sales but also on safe flight operations and pilot instruction—joined ERCO. Berliner was planning ERCO’s postwar business, and the Ercoupe was first in line.

In 1944, Berliner held a sales strategy conference with all the Ercoupe’s soon-to-be distributors. As Weick recalled in the book From the Ground Up, which he co-wrote in 1988: “The real sales push was made by Oliver Parks, a very dynamic man, who was to be the airplane’s distributor in eight Midwestern states. Most everyone expected a big postwar boom, so spirits were high.” The innovation in Parks’ plan: department stores.

Wanamaker’s stores in Philadelphia and New York displayed Glenn Curtiss’ Rheims racer and a Blériot monoplane as far back as 1909. But Parks had in mind something far more ambitious. “Salesmen for refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, radios, houses, automobiles—to name only a few—are preparing to go after the postwar market with intensive campaigns,” he wrote in Flying magazine in 1944. “None [of the competition] that I have heard plan to sit on their fixed bases and wait for Joe to come and see them. And if aviation continues the pre-war, come-and-get-it attitude, aviation—not Joe—is going to suffer. We must go after him with the most intensive, streamlined, ultra-modern sales program in the nation’s history.”

His plan was extensive. Starting with the newly formed Parks Aircraft Sales and Service headquarters in East St. Louis, there would be four regional headquarters, supporting 32 dealerships. Each dealership, based at local airports, would place a single product line, the Ercoupe, in local department stores.

Park executed his plan in June 1945, signing his first deal with Marshall Field & Co. Ercoupes went on display in October at the flagship store in downtown Chicago: one on the main floor, and one on the fifth floor in the “Store for Men.” ERCO soon signed similar deals with Macy’s, Bamberger’s, and department stores throughout the Midwest.

The initial response was everything Parks could have hoped for. Mandel’s in Chicago displayed both the Ercoupe and the Piper Cub, and reported crowds waiting when the doors opened. There were nine orders, 12 customers took introductory flights at a nearby airport, and the store anticipated 75,000 visitors over the next two weeks. Before the Ercoupe even went on display, Macy’s reportedly sold two by phone. It also had 284 inquiries (of which 82 said they planned to buy), and on the first day sold 20.

By May 1945, ERCO had taken 203 orders, and Parks’ plan continued to unfold in the Midwest. The William H. Block store in Indianapolis and St. Louis’ Famous-Barr store each reported more than 100,000 guests in attendance at a preview event. In November, the J.C. Penney in Denver became the first store in the west to offer the Ercoupe. The store sold nine the first week—one to a frozen foods businessman and another to an oilman, both seeking to ease their considerable travel time. Indeed, the retailers reported most sales were to businessmen between 40 and 50 years old, half of whom expected to use the airplane for pleasure, half for work.

The department store airplane spread to retailers all over the country and even to Canada: Gimbel’s in Philadelphia, Davison’s in Atlanta, May’s in Baltimore, Gambel’s in Ottawa, Joske’s in San Antonio, Miller & Rhodes in Richmond, Leh’s in Allentown. The boom was on and the future was bright. In late 1945, Parks filed common stock registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission to expand his operations; he was expecting sales of 1,800 Ercoupes per year. Berliner, aggressively optimistic, predicted orders of 10,000 Ercoupes for 1946. In late 1945, four Ercoupes were coming off the line every day. Berliner kept increasing the number of shifts, and by the spring of 1946, ERCO was producing 30 to 35 airplanes every day.

While newspapers covered the novelty of the department store sales, aviation journals sought out the pilots’ experiences, often coming up with amusing anecdotes about the novice flier. The Secretary of the Interior, Henry Wallace, soloed in an Ercoupe and mistakenly flew it to Baltimore instead of Washington, D.C. Entertainers Edgar Bergen and Dick Powell each purchased one, giving the Ercoupe cachet. Although not yet a celebrity, William F. Buckley Jr. bought one with his college friends (against his parents’ wishes), later landing on the lawn of his sister’s prep school and then nosing it over into a ditch.

The Ercoupe seemed to be reaching everybody. Magazine and newspaper features highlighted women pilots, usually as novelties, beneath headlines like “Any Woman Can Learn to Fly” and “A Missouri Miss Gets Her Wings.” Because ERCO could substitute another means of yaw control, legless veterans and civilians were getting checked out in Ercoupes without rudder pedals. There were heroic stories about non-pilot passengers successfully landing Ercoupes after the pilot became ill, passed out, or in one case died. Other stories were comic—Ercoupes flying Santa Clauses, wingless Ercoupes in street parades, Ercoupes getting parking tickets after being driven into town (once by a department store owner as a publicity stunt). There was even a criminal flying the Ercoupe: a 19-year-old student pilot who stole one, paying for it and a series of repairs with bad checks, with authorities chasing him all the way. His name: Charles Cessna, though no relation to the airplane maker.

Not everybody was happy about the demographics targeted for the postwar light airplane, and the department store sales tactic in particular. Many were concerned flying was being sold as far simpler than it really was. Civil Air Patrol cadet Bette Parks wrote to Skyways magazine in September 1945, “If you make it sound like a simple cinch, John Q [Public] is going to be so disgusted with all the complications—CAA rules, navigation, meteorology, etc., etc., that he won’t even go near an airplane.” A January 1946 article in Flying reported that “irate airport operators complain bitterly” about department store purchasers getting free instruction—up until they solo—and then being turned loose without any knowledge of the responsibilities that come with aircraft ownership. One purchaser didn’t even know he’d need a license.

Aviation writer Claude O. Witze darkened more clouds in his fictional conversations with a curmudgeonly character called Willie Wingflap, whom he featured in a Rhode Island newspaper, the Providence Journal. Through Willie, Witze expressed the concern that the new postwar airplanes were just pre-war designs being recycled as innovations, and although there were many veterans learning to fly on the GI Bill, few would be able to afford an airplane’s maintenance.

In the end, the killjoys called it: As rapidly as the light-airplane market boomed, it began to bust. In August 1946, ERCO was preparing for vastly increased volume projections, with Berliner estimating demand at 50 Ercoupes a day. “Then suddenly, during a single week in September, the airplanes on the field built up from 100 to 300,” Weick wrote in his book. “The dealer’s pipelines had filled up and they just could not handle any more volume.”

Berliner had to move quickly. His three shifts were cut to one, part-time. Then he shut down the Riverdale, Maryland plant for a month. The aviation press began reporting a “seasonal slump” in the light-airplane market, as had happened during the fall and winter before the war. Willie Wingflap knew better: “It looks to me,” he said, “as if the boom was only a pop.”

It was true. The manufacturers’ supply outpaced an over-predicted demand. The full-page newspaper ads and the department store showrooms disappeared. As for the light-airplane industry, Piper, Cessna, and Beech survived, but many others went under. In 1947, Berliner sold all of Ercoupe—rights, tooling, and materials—to Bob Sanders, the first of many manufacturers who would try to make the Ercoupe profitable. Ultimately, only about 5,500 were built.

Although the Ercoupe was never really successful as a commercial product, the Ercoupe Owners Club estimates more than 2,000 are flying today—a testament to Weick’s design and vision. Weick went on to make many great contributions to agricultural and civilian flying. Oliver Parks never slowed down, but donated his beloved air college to Saint Louis University, and left aviation for the business of prefabricated housing.

Just two years after the giant Macy’s New York Times ad helped launched the department store airplane experiment, another ad was published to end it. It took up no more than an inch in the classified section of the October 1947 issue of Flying magazine: Ercoupe 46. Display model with special paint job, starter, generator, and battery. 2 hours total time. $2100. Also Ercoupe 46, 25 hours total time, never damaged. $2000. Airadio—2 way, never used, $100. R.H. Macy & Co., Dept. 270, Herald Sq., NY.

Paul Glenshaw is a writer from Silver Spring, Maryland.