Case Closed

Mysteries solved, secrets revealed, and questions finally answered

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/case-closed-flash.jpg)

The Lady That Didn’t Come Home

Had it not been for some sharp-eyed British oil exploration engineers in Libya in May 1958, a B-24D Liberator named Lady Be Good might have joined the ranks of other military aircraft that went permanently MIA during World War II. Instead, the aerial survey team from D’Arcy Oil Company (later British Petroleum) inadvertently found the Lady after a 15-year disappearance, making it one of the most famous aircraft to ever lose its way home in that war.

In the early hours of April 5, 1943, the airplane was returning from a night bombing run over Italy when it overshot its base at Soluch, on the Libyan coast, and ran out of fuel. The crew parachuted into impossible odds: Eight men (a ninth was killed when his parachute failed to open) and half a canteen of water in the Libyan desert, where temperatures reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit. But the wreckage, first examined in 1959, showed the men could have survived had they not made a fatal mistake.

When ground teams first inspected the Lady, they discovered its radio still worked, as did one of its .50 caliber machine guns. The airplane lay just 16 miles south of where the crew had landed. Had they trekked south, instead of northwest, they would have found life-saving water, food, and communications equipment aboard the Lady. (They had no way of knowing their base was actually 440 miles away; the last man made it an astounding 111 miles before collapsing.)

The discovery of the bomber and crew triggered worldwide media coverage. At least two books were written, along with numerous newspaper and magazine articles, and a 1960 episode of “The Twilight Zone” (“King Nine Will Not Return”) was loosely based on the incident. Over the years, the B-24 was stripped of most of its parts and the crew’s belongings; some items went to various U.S. Air Force and Army museums. What remained of the airplane, the Libyan government removed from the desert in 1994 and stored at the El Adem military airfield in Tobruk.

Why did the Lady get lost? The official investigation report blames the rookie navigator, saying he misinterpreted a directional reading sent from Benina airfield in Libya. But Mario Martinez, author of Lady’s Men: The Story of World War II’s Mystery Bomber and Her Crew, points to a different reason: failure by another radio operator at nearby Benghazi to respond to the bomber pilot’s plea for a position report, believing the airplane to be German. “Failure to acknowledge this call was probably the reason the Lady Be Good flew on and disappeared,” Martinez writes on his Web site, ladybegood.com.

Bombers from World War II still turn up today, mostly in the Pacific. “There are hundreds of crash sites in places like Papua New Guinea, with full skeletal aircraft remains plus crew remains, because culturally they [Papuans] do not touch sites like that, [mindful of] the aura of death,” says Larry Greer, a spokesman for the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office in Arlington, Virginia.

Paul Hoversten

Roswell: A Hotbed of Conspiracy Theories

Which incident of the 20th century is responsible for more analysis, rehashings, and conspiracy theories: the Kennedy assassination or the Roswell incident? Each left in its wake copious details that are difficult to interpret. Decades later, amateur scholars pore over them with a level of attention that is almost molecular.

On June 14, 1947, rancher Mac Brazel found scraps of rubber, paper, tin foil, and sticks in a field north of Roswell, New Mexico. On July 8, the Roswell Army Air Field issued a press release announcing that military personnel had discovered the remains of a “flying disc.” But later that day: Recall. The debris hadn’t come from a flying saucer, said Eighth Air Force Commanding General Roger Ramey, but from a weather balloon. It wasn’t enough. Over the decades, the story grew to include aliens in the saucer, secret autopsies of the aliens, autopsy witnesses disappearing....

In 1994, Congressman Steven Schiff of New Mexico, after repeated inquiries from his constituents, commissioned a General Accounting Office study to try to hash it all out. The conclusion: The culprit was Project Mogul, a then-secret program in which balloons sent up to 40,000 feet used sonobuoys to listen for evidence of Soviet nuclear tests. The explanation got a boost in 1997 from the book UFO Crash at Roswell: Genesis of a Modern Myth (Smithsonian Institution Press); in it, Mogul scientist Charles Moore lays out detailed weather data he says shows how one balloon could have left the debris.

The Mogul explanation isn’t universally satisfying. Saucerologist David Rudiak claims Moore cooked his meteorology. (Moore, who died in March, would not debate Rudiak’s challenges.) Rudiak also examined a photograph of General Ramey taken the day he issued his saucer denial: Ramey holds a piece of paper, and Rudiak, having blown the picture up, insists the paper bears the words “victims of the wreck.” The GAO counters that a “national level organization” examining the photo found nothing of the kind, and that Roswell is, and always has been, a saucer-free zone.

Perry Turner

One Giant Oops for Mankind

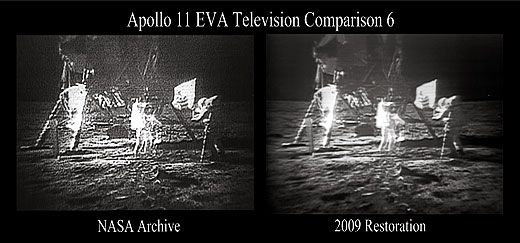

In 1999, John Sarkissian, a scientist at the Parkes Radio Observatory in Australia, began hunting for original Apollo 11 recordings of the TV signal beamed from the moon during Neil Armstrong’s historic “step” on July 20, 1969. Sarkissian, who worked as a technical advisor on The Dish, a movie about Parkes’ role in the mission, knew that the ghostly black-and-white film seen by hundreds of millions on that momentous day wasn’t what was transmitted from the moon. Only a handful of people at Parkes and two other tracking stations, Goldstone in California and Honeysuckle Creek in Australia, saw that. The rest of us saw a degraded picture that had been converted to a format commonly used by broadcasters of the day.

So what happened to the original, clear TV pictures? They were recorded on one-inch magnetic tapes and sent to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. But after more than a decade of searching by Sarkissian, Richard Nafzger of Goddard, and half a dozen others at various U.S. and Australian institutions, nobody has been able to put their hands on the tapes.

The most likely conclusion, NASA determined last July, is that it recorded over them in 1981, when a shortage of one-inch magnetic tapes led the space agency to reuse old ones in storage.

More than once, the search team thought they had located dubs of the original TV recordings. In one case, it was a tape stored for 36 years in the garage of a retired employee of the Australian Honeysuckle tracking station. All that time he had thought it was the Apollo 11 moonwalk, but it turned out to be simulation data from 1967.

There are no villains in this story. What looks in hindsight like a colossal blunder has a simple human explanation: No one in the 1970s, when the tapes were being stored at various archives, flagged them as being especially valuable. After all, the viewing public had seen the broadcast signals as the government had planned, and there was no digital technology yet to convert the original telemetry tapes to usable pictures. Still, NASA last year arranged for the broadcast-quality tapes to be digitally enhanced to improve the scenes we saw all those years ago. The space agency released the tapes as the nation marked the 40th anniversary of the moonwalk.

Tony Reichhardt

Who’s Afraid of the Bermuda Triangle?

Not long after World War II, a heavily trafficked patch of the Atlantic Ocean began gaining a reputation as a place to avoid: A number of airplanes and ships had vanished after entering a triangular area, its three points in Miami, Puerto Rico, and Bermuda.

One of the more famous disappearances happened on December 5, 1945, when five U.S. Navy TBM Avengers on a training mission were lost. The compass of the lead airplane malfunctioned, and all the airplanes probably ran out of fuel. One of the search-and-rescue aircraft, a PBM-5 Mariner, also disappeared; the Navy chalked it up to a mid-air explosion. In the late 1940s, several commercial flights, including a Douglas DC-3 and an Avro Tudor IV, vanished as well, causing the public to wonder what was going on in the area that became known later as the Bermuda Triangle. (The term was coined in a 1964 article in a U.S. pulp magazine.)

“People were scared in that whole cold war era. They didn’t expect airplanes to go missing,” says Dorothy Cochrane, an aeronautics curator at the National Air and Space Museum. “You had a lack of communications technology, and meteorological science wasn’t all that great. So it gave rise to all these theories.”

It wasn’t long before magazines like Fate and Argosy put a supernatural spin on the disappearances, and the Triangle became topic A for fans of the paranormal.

For serious thinkers, the case of the spooky Triangle has been closed since Larry Kusche wrote his landmark 1975 book The Bermuda Triangle Mystery: Solved. Today, hurricanes, human error, and compass variations and deviations are only a few of the culprits that cause the Navy and the Coast Guard to conclude that no more airplanes and ships are lost there than in other regions of the world with similar climate and shipping or air traffic. Oh, and the purported releases of methane from the sea floor that turn the surface into a ship-swallowing froth? Some people believe it. The Skeptic’s Dictionary Web site (skepdic.com) calls it “oceanic flatulence.”

Michael Klesius