Checking In…

…on the Missing Persons File

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Checking_in_on_the_missing_person_FLASH.jpg)

Amelia Earhart

America’s most famous woman pilot vanished on July 2, 1937, with navigator Fred Noonan, en route to Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean during an around-the-world flight in a Lockheed Electra 10E. Want the details? See Amelia Earhart by Doris Rich, Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved by Elgen and Marie Long, East to the Dawn: The Life of Amelia Earhart by Susan Butler, or some of the other 50 books about or by Earhart; the 2009 movie starring Hilary Swank, the 1994 one with Diane Keaton, or the 1943 Rosalind Russell version. But in a nutshell: She’s still missing.

Patricia Trenner

Charles Nungesser and François Coli

When this magazine last left our heroes—the two French pilots who got lost crossing the Atlantic in an attempt to win the $10,000 prize that Charles Lindbergh bagged 12 days later—their remains and their airplane were being sought in Maine’s inhospitable backcountry. That was in February 1987, when Air & Space sent a reporter along on a search for the aircraft, L’Oiseau Blanc—the White Bird.

Charles Nungesser and François Coli had left Paris for New York on the night of May 8, 1927. A woodsman near the Maine town of Machias reported hearing an airplane above the clouds on the afternoon of May 9, and his story circulated among the locals for years. Searches of the area in the 1980s turned up nothing, but launched The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (which later earned fame for claiming it had found a piece of Amelia Earhart’s shoe). Twenty expeditions and 23 years later, TIGHAR founder Ric Gillespie, citing testimony reported in a 1927 New York Times article, has moved his search from Maine to Newfoundland. The Times noted that New Yorkers were “ scanning the dripping skies and devouring eagerly false reports of [the aircraft’s] appearances along the Newfoundland and New England coasts.” Gillespie believes some of the reports weren’t false. “Several people along the [Newfoundland] coast went to the magistrate and swore what they saw on the morning of May 9 in affidavits,” he says. “The reports are 20 to 30 miles apart, and they line right up.” On Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula, residents have told of an airplane crashing in one of the area’s many lakes. Gillespie has traveled several times to an area, dotted with ponds, that he could reach only by helicopter. On his next trip he hopes to search with LIDAR—light detection and ranging technology. He says, “I would rather find the White Bird than Amelia Earhart.”

Linda Shiner

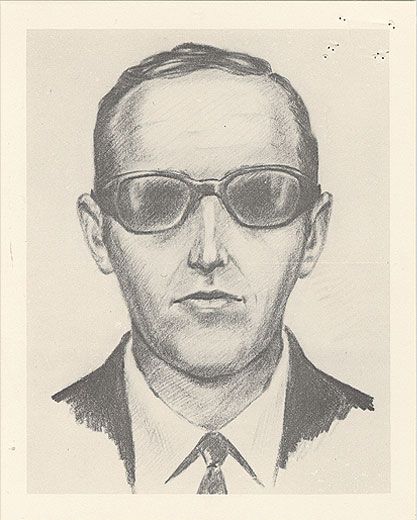

D.B. Cooper

On the evening of November 24, 1971, a 40-something man paid cash for a one-way ticket from Portland, Oregon, to Seattle, Washington, aboard Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305, a Boeing 727. He told the ticket agent his name was Dan Cooper.

During the flight, Cooper told a flight attendant he had a bomb in his briefcase, which he would detonate if $200,000 in cash and four parachutes weren’t waiting at the Seattle airport. They were. After landing, Cooper allowed all passengers to be released. He told the flight crew to fly to Mexico City. Somewhere over southwestern Washington, Cooper jumped from the rear exit into below-freezing temperatures and a driving rain. He had left behind a J.C. Penney tie, a tie clip, and two parachutes.

In the following days, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had interviewed a D.B. Cooper, according to a Portland, Oregon wire service reporter, and though the man was eventually cleared, the Northwest hijacker was forever after known by that name. The question of what happened to Cooper and his bag of loot has become one of the FBI’s best-known unsolved cases.

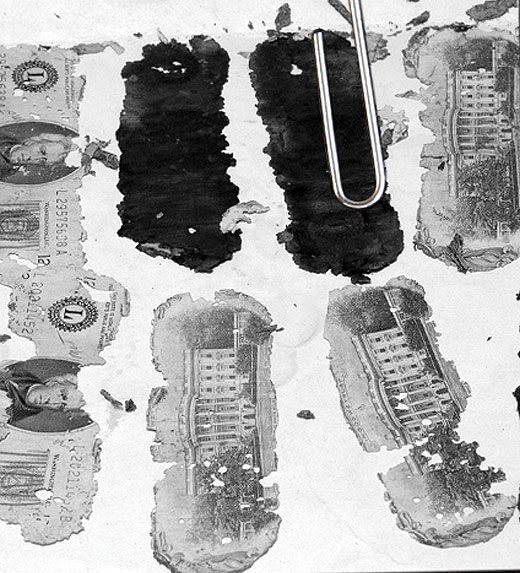

In 1980, eight-year-old Brian Ingram found a bundle of tattered $20 bills totalling $5,800 buried along the banks of Washington’s Columbia River. The serial numbers identified the bills as part of the money Cooper had demanded.

In 2007, the FBI released new information, including a photograph of Cooper’s black tie, from which a DNA sample was obtained. Last year, an FBI agent unveiled a possible profile of Cooper as a loner who might have worked as a cargo loader in the U.S. Air Force (hence the familiarity with parachutes) before taking, and later losing, a job in the civil aviation industry. After 39 years, the FBI is still searching.

Diane Tedeschi

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

In 1998, a bracelet bearing the name Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, along with the name of his wife, Consuelo, was fished out of the Mediterranean Sea. The French aviator and author had disappeared on July 31, 1944, while flying an F-5B, a reconnaissance version of a Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Two years after the bracelet was recovered, a diver located parts from an F-5B off Marseille. In April 2004, French authorities announced that the parts were indeed from Saint-Exupéry’s aircraft. But what had brought it down? Enemy fire? Though the fragments retrieved from the sea had no bullet holes, there were too few pieces to rule out a hit. German pilot Horst Rippert believes he likely shot down the F-5B, but his claim has not been verified. Was it suicide? Or simply an accident caused by the sometimes careless Saint-Exupéry?

Patricia Trenner