How Perry Young Broke Aviation’s Color Barrier

A black pilot and a small helicopter airline moved faster than the speed of law.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/20/e020122a-f8ee-4b18-af29-64f8ba86e280/08i_fm2019_img820_live.jpg)

For many years, Perry Young could be identified by his Chevy Blazer, which prominently displayed the words malgré tout on the bumper. The phrase means “in spite of it all” in French, a language Young learned while flying small aircraft in Haiti during a time when no scheduled American passenger carrier would hire a black pilot. And in spite of it all, Young broke that barrier.

He was born in 1919 in Orangeburg, South Carolina. His father Perry Senior and mother Edith were both university-educated, but the family lived on the elder Perry’s salary as a tailor. In 1929 they moved to Oberlin, Ohio, because Perry’s parents thought living in a college town would mean better educations for the family’s four children.

Perry Jr. graduated in the top quarter of Oberlin High School’s class of 1937. He enrolled at Oberlin College, intent on becoming a medical doctor, but between finishing high school and starting college, he went for a ride in an airplane and decided, hard and fast, that nothing on earth compared to soaring above it. “No matter how hard I tried doing other things, I kept drifting back to airplanes,” Young later told a New York Mirror reporter. While a college freshman, he worked odd jobs for $9 a week and spent the proceeds at the airport, where $5.25 bought a 20-minute flight lesson. Young soloed after just three hours and 20 minutes of instruction, and on August 14, 1939, at barely 20 years of age, earned his private pilot’s license.

In Young’s sophomore year, his father moved to clarify priorities. As Shakeh Young, Perry Jr.’s widow, recalled, “His father said, ‘You have to [continue to] go to college or leave.’ So he left.” Young moved to Chicago, where the Coffey School of Aeronautics had in 1938 been founded as the country’s first flight school owned and operated by blacks—and one of the only places in the country guaranteed to accept black students. At Coffey, Young earned his commercial pilot’s license. The following year, faced with imminent global conflict, Congress passed the Civilian Pilot Training Act, which required that African-Americans be included in civilian pilot training, and Public Law 18, which eventually resulted in an African-American military flying unit. The Army, which held the official view that black people were incapable of learning to fly as well as whites, had bent only slightly: Black pilots would be trained to fly and sent to combat but only in segregated units ultimately commanded by white officers.

The decision to allow African-Americans to fly gave birth to the famed Tuskegee Airmen, named for their main training base at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. Perry Young joined the Airmen as one of 40 black flight instructors. Then-trainee Lee Archer later recalled, “Very few of us knew anything about flying—few blacks did—and we thought our instructors were going to be white. When I saw men like Perry Young, I was surprised and proud. They were like minor gods to me.” Young, despite his new deity status, was younger than most of those he instructed.

In all, 992 pilots trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field; 150 took instruction from Perry Young, including George “Spanky” Roberts, who became first commander of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first black aviation unit to see combat. The Tuskegee flyers went on to set an enviable standard: More than 100 members were awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses. In 2007, the Tuskegee Airmen collectively received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

But Perry Young received no such decorations during his lifetime. As authors Lynn Holman and Thomas Reilly wrote in Black Knights: The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen, “The black civilian flight instructors were obviously the lifeblood of the program” and were considered too valuable to risk in combat. Maury Reid, a 1944 Tuskegee graduate, recalled seeing “one of the saddest things. I had graduated, and a couple of these flight instructors came down to watch me climb into that P-40 and take off. They wanted to be [in combat] so badly.” For Young, being denied a combat role was a long-running grievance. “He didn’t want to be an instructor who trained cadets,” says Shakeh Young. “He wanted to be a cadet. He wanted to fly.”

Other disappointments followed. Post war, bolstered by a flood of demilitarized transport airplanes and a soaring economy, many ex-military pilots found jobs in civilian aviation. Not Young. He sent out stacks of applications but never got past the first interview when it became obvious that he was black. As Young later told a reporter, “I had come up with a different-colored skin, and there wasn’t much I could do about it.” Grounded at home, Young headed to the Caribbean. He and two friends set up a small airline in Haiti, but it foundered after two years. After several other short-term jobs fell through, he finally landed a position flying light aircraft for the Puerto Rico Water Resources Authority, which in 1954 sent him to Connecticut to qualify as a helicopter pilot.

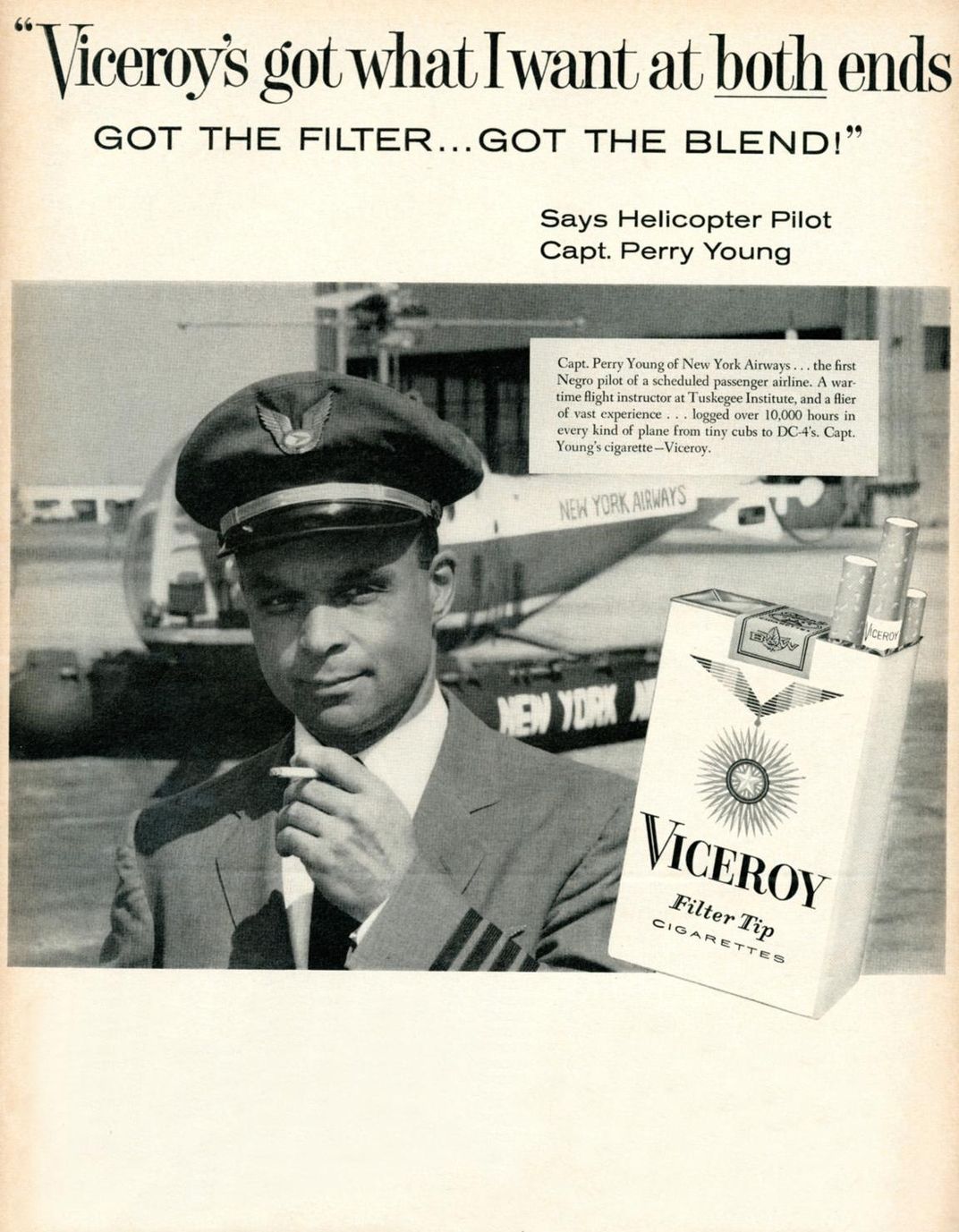

In 1955, Young once again applied to mainland carriers. One application went to New York Airways (NYA), a small helicopter company that shuttled passengers and luggage between New York’s LaGuardia and Idlewild (later Kennedy) airports and New Jersey’s Newark Metropolitan. By ground, Idlewild to La Guardia could be a two-hour slog; by helicopter, the journey took 10 minutes and offered a panoramic view of Manhattan. NYA’s managers decided to “break the color line” in aviation in the hope—according to one company official—that hiring aviation’s “Jackie Robinson” would bring good publicity to their little service.

Even so, NYA initially rejected Young. His 7,000 hours of flight time included only 200 on helicopters, well shy of the company’s 500-hour minimum. Young left Puerto Rico for remote Baffin Island, Canada, where he had secured work as a mechanic for a small airline contracted to fly personnel and supplies to even more remote radar installations. After seven months in the cold (and a mild case of frostbite), Young found work in the Virgin Islands.

As Young bounced around, NYA moved to replace its single-pilot Sikorsky S-55s with larger S-58s, which required co-pilots, and added service to Manhattan’s West 30th Street Heliport. New York Airways tracked Young to the Virgin Islands and offered him a contract, and on Monday, December 17, 1956, Young was officially hired as the first African-American pilot for a scheduled U.S. airline. Intense training followed.

Hiring Young created the publicity NYA desired. The New York Times gave the story 14 column-inches and a photo. Other press reports described Young, then 37, as good-looking, soft-spoken, and hesitant to talk about his achievements. Young told the papers that he had two goals: to open the door to other black pilots and to eventually become a pilot for a major carrier. Not until 1963, when ex-Air Force captain Marlon Green won a Supreme Court case against Continental Airlines, did major carriers reluctantly start hiring black pilots. And no major carrier ever hired Perry Young. Still, a wall had been breached. The New York Mirror’s February 5, 1957 edition reported:

With Perry Young as the co-pilot, the 12-passenger helicopter rose three feet from the ground, hovered gently for a moment, then, pointing its snub-nose down, soared straight up from LaGuardia Airport. In nine easy “bumpless” minutes we were at Idlewild…. Perry Young is unique because he is the first Negro pilot hired by any scheduled airline in America.

Young was not welcomed with entirely open arms, says former NYA pilot Frank Covie, who was then doing promotional work for NYA. Two white pilots initially refused to take Young as a copilot. That changed, Covie adds, not through any change of heart, but because NYA was too short-staffed to indulge the pilot’s prejudices. Within months of his hiring, Young moved to the captain’s seat.

Covie told me about Perry Young over cheeseburgers at the Falcon’s Nest, an airy pub in Fernandina Beach, Florida, that houses a museum dedicated to the airmen of World War II. The wall display includes both the New York Times story on Young’s hiring and the obituary that paper published upon Young’s death in 1998. Covie, now 86, still projects a sense of command from his time as a jetliner captain, a career he says he owes to Young.

Covie became smitten with flying during his youth in Queens, New York, but lacked the money for flight lessons. He wormed his way into aviation as a baggage handler and had worked his way up to doing promotional work at NYA when Young was hired. “He talked about life as adversarial,” Covie said. “You had to come through it the hard ways.”

Covie sought Young’s friendship, and the two gradually bonded. A year after they met, Perry Young started bringing Covie to Westchester County Airport and teaching him to fly, free of charge, as Covie hustled the money needed to obtain a commercial pilot’s license—which he then used to become a pilot for New York Airways. Covie eventually left to fly for American Airlines, then as now one of the biggest airlines in the world. “Do you know how that hurt?” asks Shakeh Young. “The one he trained for free got the job he couldn’t get. That was very hard.” Young and Covie remained lifelong friends, however, and it was Covie who delivered the eulogy at Young’s funeral.

Even when he wasn’t battling to realize his dreams, Young was rarely at rest. His daughter, Linda Young-Ribeiro recalled, “Every day when Papa would arrive home, he would ask his three children ‘What did you accomplish today?’ We had to have an answer.” Her father would then change his clothes and head either to his workshop, where every tool had its place, or to some backyard project. Aside from flying, his daughter says, Young enjoyed nothing more than working with his hands. He bought a junked Volkswagen Beetle, she said, and “transformed it into a glistening jet-black beauty.” He acquired a derelict Cessna, restored it to airworthiness, and sold it. Young, by universal recollection, did not expect the world to give him anything without working for it, and he passed that attitude of self-reliance on to his children. When a high school-age Linda asked for money to buy clothes, Young granted only enough for the material she needed to sew her own. Which she did.

Young had ambitions beyond puddle-jumping between New York airports, although his dreams of flying for a major airline never came to fruition. In 1957, he returned to Puerto Rico with Covie and to the idea of establishing an air taxi service. On the way home, staff at a Miami hotel insulted Young with a racial slur and refused him accommodations. Covie started to make a scene, then Young put a hand on his shoulder, “It’s okay. Let’s go.” It was, for Young, just one more insult to shrug off.

In the meantime, New York Airways was expanding. In 1958 the airline added 15-passenger Boeing Vertol 44 helicopters and began service to White Plains, Long Island, and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Passenger demand climbed quickly.

Helicopter flying was tough on the nerves and tough on the back, and Perry Young was not the only NYA pilot who eventually required back surgery. The flying was repetitive: a short jump from one airport to another, followed by a short wait for passengers to disembark and others to board, then back into the air; repeat up to 20 times over a six-hour shift. When the weather turned bad, some flights had to put down wherever was safe. “We did a landing in Flushing Meadows,” former NYA pilot James Brundige recalled, referring to the park in Queens that today is the site of the U.S. Open tennis tournament. “Passengers weren’t concerned about their safety but about missing their flight.”

NYA pilots were a small fraternity from which Young kept somewhat aloof, sometimes wryly so. One day, he and staff members returning from lunch stopped at a pharmacy. One woman purchased a tube of “ManTan,” a then-popular skin-tanning agent, then casually asked Young if he had tried it. Equally casually, Young replied, “The Good Lord supplied me with his own.”

NYA’s major expansion came in 1962, when the company acquired 25-passenger Vertol 107 helicopters. The larger and faster helicopters allowed NYA to start flying to Morristown, Princeton, and Trenton, New Jersey; New Haven, Connecticut; and more points on Long Island. Within six months, the new helicopters had carried 200,000 passengers. NYA officials talked optimistically of million-passenger years in the future. In 1965, New York City gave NYA permission to establish a rooftop heliport atop the 59-story Pan Am building, directly above Grand Central Station in midtown Manhattan. The New York Times crowed that “the city’s first skyscraper heliport—a half-acre concrete pad 800 feet above the Grand Central Terminal district—has become a resounding hit with travelers.” The selling point was unmatched convenience: Passengers could check in at the heliport just 45 minutes before their scheduled departure from Idlewild and easily make the connection. But NYA’s finances continued to flutter; federal subsidies ended, and even as service increased, a variety of makeshift financings followed.

Travelers may have enjoyed the convenience of landing on the Pan Am building’s roof, but NYA pilots did not. Pilot Deene Sanders recalled, “You had very little room for error. You’d start your approach at about 1,300 feet and gradually descend. If you didn’t have the right descent, you’d loop around the building and make a second approach.” A few pilots simply refused to land there at all.

But when NYA ran into safety problems, they had nothing to do with difficult landings. On May 16, 1977, a Sikorsky S-61 was taking on passengers at the Pan Am heliport when its right-hand strut collapsed and the helicopter fell on its side. The turning rotors slashed through waiting passengers; three died instantly, and a fourth died in the hospital. One blade plunged off the roof and claimed the life of a pedestrian on the sidewalk below.

Federal investigators attributed the snapped strut to metal fatigue, a finding that startled NYA. Checking for strut wear, they said, was not part of the manufacturer’s recommended maintenance. The heliport was immediately closed.

Disaster hit again less than two years later, on April 18, 1979, when another Sikorsky S-61 crashed while attempting an emergency return to Newark International Airport. Three passengers died, and 13 were injured. New York Airways suspended operations. Within days NYA filed suit against Sikorsky, furloughed every one of its 180 employees, and filed for bankruptcy.

Although he was not involved in either crash, Perry Young, at 60, was unemployed but not ready to retire. He was soon hired as chief pilot by Island Helicopter Corporation (of Long Island). He continued to fly until March 1986, when at age 67 he was grounded by the FAA’s mandatory age restrictions.

In retirement, Young continued to go his somewhat stubborn way. Shakeh Young recalled, “Whenever I said, ‘Let’s buy something new,’ he’d find something old and fix it.” The couple lived on a 6.5-acre plot in Pine Bush, New York. For Young, the tract was something of a refuge. He read regularly: aviation journals, history, T. Boone Pickens on investing, Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, and William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. He was more a listener than talker, his widow remembered: “If he knew something, particularly if it was aviation, he would say. If you said something he thought was stupid, he was not someone who would shame you by telling you so.”

Until his death in 1998, Young kept a busy retirement. He began the day by reading The New York Times, completing the crossword, then tackling various household chores. He tended an extensive garden, nurtured peach trees, poured the concrete for a patio, and spent years gathering stones to build a three-foot-high wall along the driveway. Chores complete, he would clean up and head out to the Orange County (New York) Airport. Young no longer owned an airplane of his own. Occasionally, he took a ride with another pilot. Mostly, he just watched what was going on, and talked to the other pilots there about the one thing that had held him in its thrall since he was 18 and got a ride in an airplane.