80,000 Ways to Search the Archive

Plumbing the secrets of the Museum’s Tech Files.

:focal(767x362:768x363)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/41/8a411b3a-196f-45f1-bc13-cd1c88901720/16a_fm2018_t8a4764_live.jpg)

The information explosion came early to the National Air and Space Museum, which houses more than 17,000 cubic feet of material documenting its collection of artifacts. But until recently, a major portion of the archive was available only to those who could visit in person.

If a researcher wanted information about the flamboyant, flying-obsessed 1920s socialite Mabel Boll, aka the Queen of Diamonds, she would look at the bound index in the archives and hope to find a typed listing under “Biographies; Individuals.” Someone looking for details about the Cactus Kitten, a monoplane-turned-triplane, would have to already know the aircraft was a Curtiss-Cox racer before asking to see the “Aircraft, Curtiss” file. And if you were interested in popular theories on how space travel would affect humans as a species? You’d need an archivist to direct you to the “Social Impact; Space History” files, where you could read Waldemar Kaempffert’s ideas about transforming bipedal humanity into quadrupeds to better scamper around Venus.

Welcome to the Technical Reference Files.

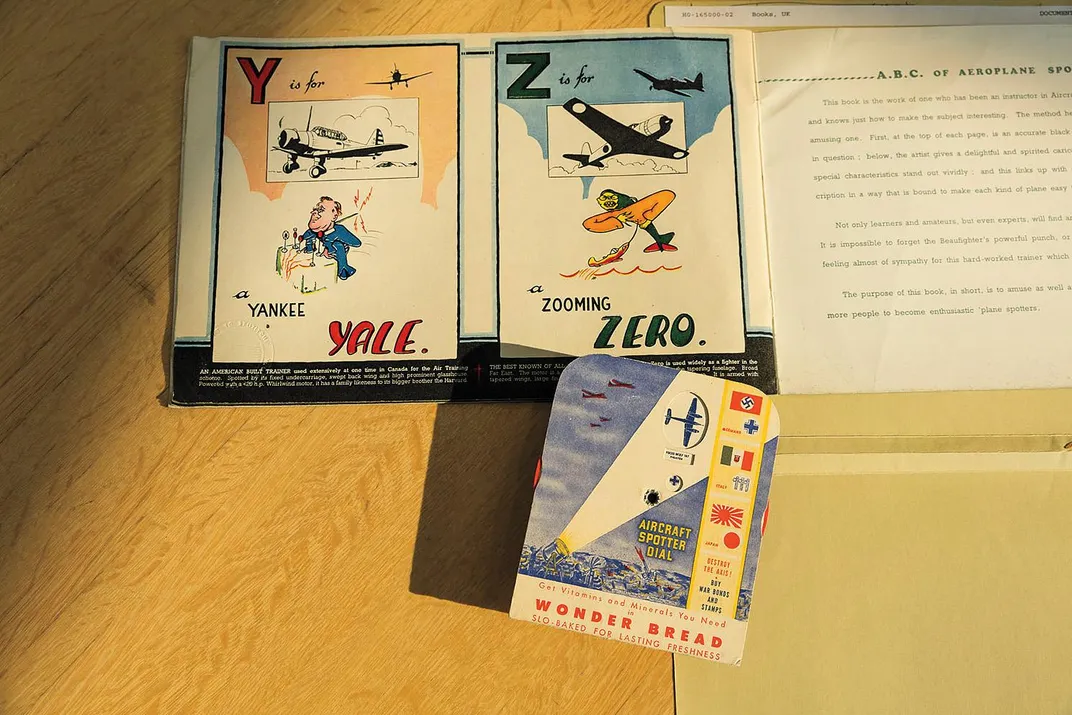

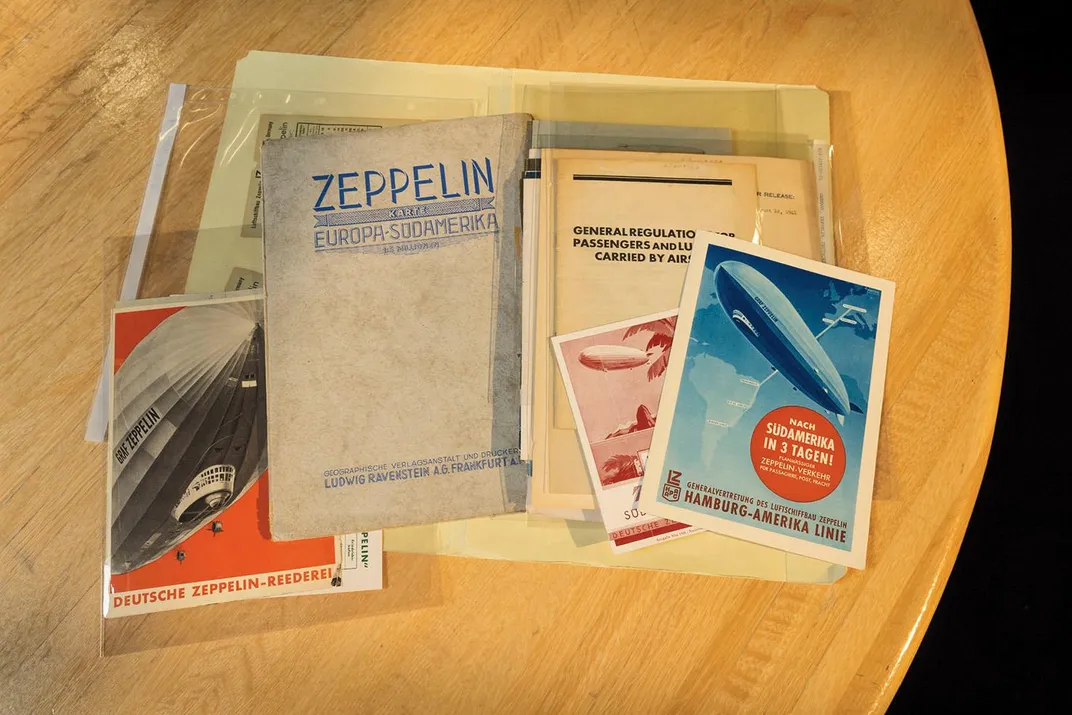

The Tech Files, as they’re known, are much like vertical, or information, files you’d find in a library, folders maintained alphabetically by subject. But in addition to the traditional newspaper clippings, the Museum’s Tech Files include photographs, correspondence, manufacturer brochures, timetables—all sorts of ephemera. “The Tech Files were first organized in the 1940s,” says supervisory archivist Patti Williams, “and placed together as soon as the Museum was established in 1948. But individual curators had been collecting archival material to support aeronautical artifacts since Samuel Langley was Secretary of the Smithsonian.” (The aviation pioneer was Secretary of the Institution from 1887 to 1906.)

Last May, the archives posted an online finding aid to the Tech Files, a project that took three years to complete.

The archives receives more than 2,500 reference requests from the public each year, and most of those queries can be answered with information in the Tech Files. Information on more than 80,000 topics, organized under 22 broad subject headings, is now available online.

To demonstrate the breadth of the collection, Williams enters the search term “Boeing,” which pulls up the archive’s 682 separate files relating to Boeing aircraft. “We don’t just have one file for the B-17,” says Williams. “We have one for the B-17A, the -17B, -17C, -17D, -17E, and -17F. We have one for the B-17F Flying Fortress, which is slightly different than the Boeing XB-17F.”

The finding aid provides file title information, and indicates whether the materials within the files are documents or photographs. But even the title information is a boon to researchers, says Williams, and will allow them to search the database before they visit. “They can see that we may have a lot of things on a specific topic or not much, and perhaps they should schedule a second visit to someplace like the National Archives while they’re here.”

Major aerospace companies have many files—for Lockheed, there are 801. Smaller aviation companies, some no longer in business, may have only one.

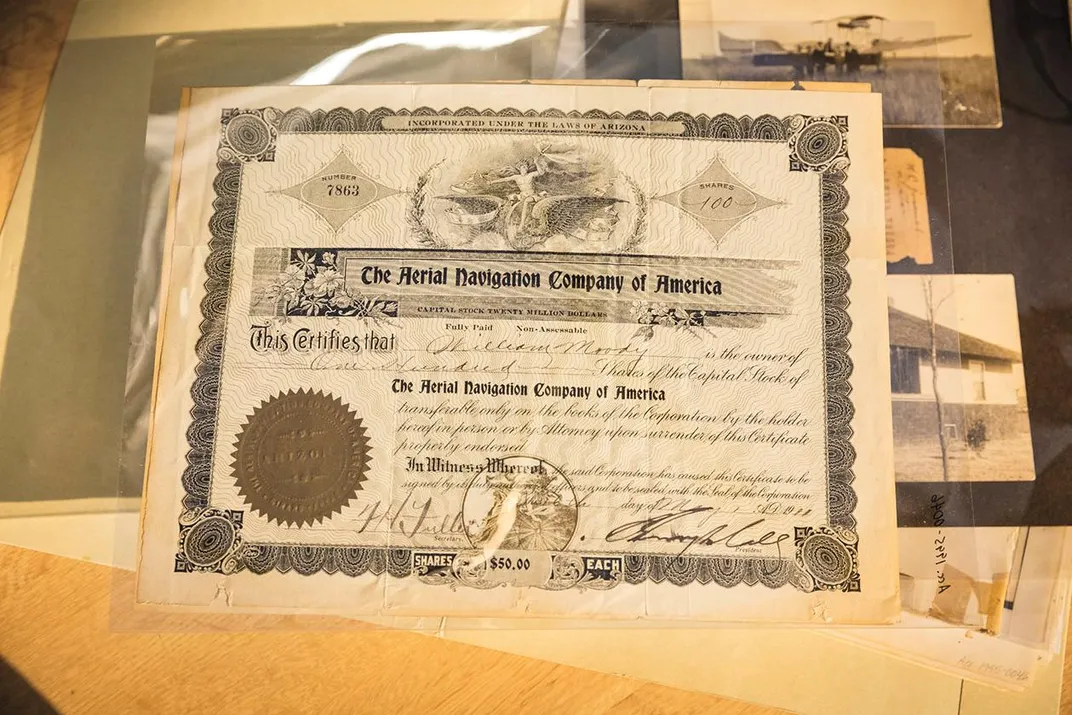

Consider the Aerial Navigation Company of Girard, Kansas. The company was founded in 1908 by lawyer Henry Laurens Call, who wanted to build a huge airplane to transport a delegation of socialists to their party’s convention in Chicago that May. His ungainly aircraft—which looked like the lovechild of a Conestoga covered wagon and several lines of flapping laundry—never became airborne. Although the company went bankrupt in 1912 and isn’t well known, fragments of it exist in the Tech Files: stock certificates, orginal photographs of Call’s machine shop and his 1912 Monoplane, and newspaper clippings quoting chief mechanic William Moody: “[We] would take a new plane along the flag-draped streets of Girard, marching to the music of the town band, to the flying field where the ship would be put through its maiden flight. But the return trip to the shop frequently was made in an entirely different manner. More than once [we] sneaked back into town through side streets and dark alleys with the remains of the new ship in wheelbarrows.”

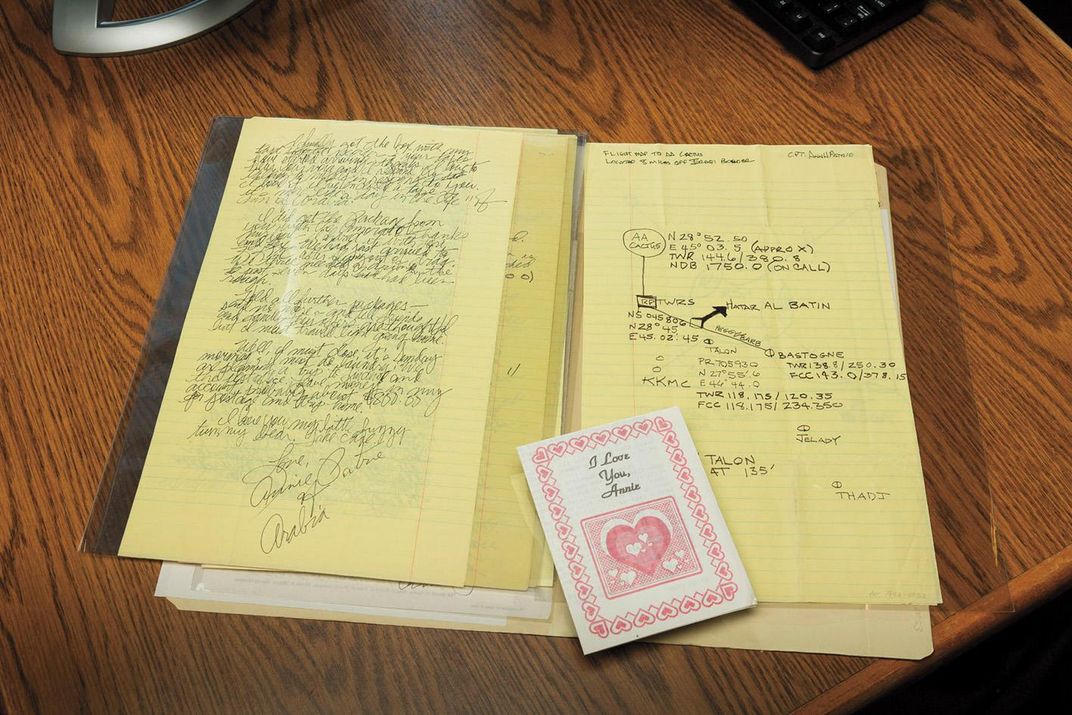

If the quaintness of this record leads you to believe that the Tech Files feature only items collected decades ago, that’s wrong: The Museum adds to the collection regularly. Williams’ most recent acquisition is information relating to Lieutenant Esteban Hotesse, the first known Dominican to serve with the Tuskegee Airmen, who died in 1945 in a B-25 crash. The material was donated by the Dominican Studies Institute at the City University of New York.

The archives staff hopes to obtain more information about minorities and women in aviation, as well as personal experiences from Korean and Vietnam war veterans. “These are important stories,” says Williams. “You can find a lot of the ‘what’ on the internet; for the ‘why,’ you come here to look at our collections.”