Pack Man

Charles Broadwick invented a new way of falling.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pack%20Man%20FL.jpg)

Parachute designs have been around since the 15th century, but in the 1880s, they were still a rare sight, so it’s hard to say what inspired 10-year-old John Murray, a poor boy in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to design his own parachute. According to a later account in the San Francisco Examiner, the boy took “a piece of tissue paper, some twine, and an exceedingly disgruntled cat, undesired in the neighborhood” and fashioned a parachute, then dropped the surly aeronaut off a high bridge. As the tissue canopy filled with air and the parachute glided off for half a mile, the boy could see his future.

At 13, Murray made his first ascent with a hot-air balloon. He planned to ride the balloon down as the air cooled. But once in the sky, he found the balloon was ablaze, most likely due to a spark from the wood fire that supplied the hot air. The boy climbed up the balloon and used his coat and a sand bag to put the fire out. He landed unharmed, but the close call must have reinforced his respect for a dedicated method that would bring someone down safely from a great height.

By age 16, he had taken the stage name Charles Broadwick, and was performing in venues like fairs and resorts, and entertaining crowds with an act in which he would ascend with a balloon and float back down with a parachute.

The preparation was as much a part of the show as the ascent and drop. A crowd watched as the 90-foot-high balloon, filled with hot smoke, fought to rise. A dozen or more strong men held down its tethers. Meanwhile, Broadwick inspected his parachute rig, stretched on the ground. The apparatus was simple, and weighed about 40 to 45 pounds. The canopy was made of heavy muslin strips that were stitched together lengthwise to form a dome.

The rim of the dome was connected by suspension lines to a trapeze, which the parachutist would grasp. The limp canopy was suspended from the bottom of the balloon by a rope, which ran through a mechanism with a blade embedded in it. When the aeronaut was ready to cut the parachute free, he would tug on a long cord attached to the blade, severing the rope and releasing the parachute from the balloon.

Once the parachute was inspected and the balloon filled, Broadwick would duck into his nearby tent and don his spangled tights. He would then ring a loud bell, dash out to the balloon-and-chute rig, grasp the trapeze bar, and shout, “Let go!” The men released the ropes and the balloon shot up, with Broadwick running briefly until the balloon pulled the parachute and him aloft. Upon reaching a height sufficient to ensure the parachute would fill with air as it dropped, Broadwick would cut himself and his parachute free.

Relieved of its weight, the balloon would twist over, belching out black smoke, and fall to the ground. Briefly, Broadwick would plummet—eliciting gasps from the pompadoured ladies and bowler-hatted men. But as the chute filled with air, his speed would slow, and the canopy would waft him—usually gently—to the ground.

Although aeronauts ballyhooed the risks, sometimes parachuting from a hot-air balloon really was “death-defying.” In fact, in 1905, Broadwick watched his beautiful companion, known as Maude Broadwick, fall to her death after getting caught up in the balloon’s tethers. Another common danger was ascending in a closed area. The aeronaut—suspended 30 or 40 feet beneath the balloon—could be slammed against nearby buildings or trees, and seriously injured or killed.

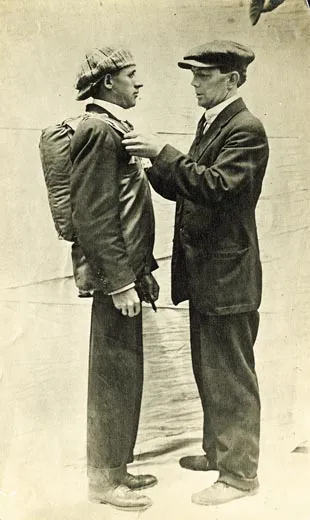

In 1906, Broadwick demonstrated an ingenious solution he had devised to protect the parachutist from such dangers. He simply folded the canopy and its suspension lines into a pack, which he then strapped to his back. Broadwick ascended while tethered directly to the balloon—just 12 feet below it, rather than 40.

What deployed the parachute was a lightweight cord called a static line. One end of this line was attached to the balloon, and the other to the peak of the parachute canopy. As the jumper left the balloon, his weight would pull the static line taut, and yank the parachute from the pack. The line would then snap, and the canopy, filled with air, would float the aeronaut to earth.

Broadwick took pride in his craft, but money was always the master. Aeronauts, like other entertainers, continually sought fresh additions to their acts: lions, monkeys, explosives, one-armed men. Broadwick was about to discover a perfect drawing card: a spitfire of a young woman named Tiny.

In the spring of 1908, Broadwick was performing with the Johnny J. Jones Exposition Shows, touring the South. Georgia “Tiny” Jacobs, 15, a deserted wife with a baby daughter, had hitched a ride with friends to see Jones’ carnival in nearby Raleigh, North Carolina. Due to a farmers’ strike, Tiny was on hiatus from her grueling cotton mill job. Watching Broadwick’s spectacular show, she resolved: “That’s what I want to do.” While the rest of the crowd ran off to witness his landing, Tiny waited for Broadwick to return to the launching grounds. She desperately wanted to be an aeronaut. The story goes that Broadwick needed convincing, but after he got her mother’s permission and in turn promised to send money back for the baby, he added the young woman to the troupe.

As the Jones shows continued to tour the South, “Tiny Broadwick” became an instant headliner. Just under five feet tall and dressed in a ruffled dress, bloomers, and bonnet, “the Doll Girl” was usually described as younger than she was, and almost always referred to as Broadwick’s daughter. (Interestingly, she was sometimes referred to as his wife. Even a member of Tiny’s family is unclear on what the relationship was.)

As Charles and Tiny plied their balloon-and-chute trade on the carnival circuit, aviation advanced rapidly: Smoke balloons became antiquated; dirigibles, passé. The aeroplane had arrived. In 1912, on a field south of downtown Los Angeles, crates full of engines, bamboo frames, and white canvas wings were being pried open, and the parts assembled into monoplanes and biplanes for the third Dominguez Air Meet, which newspapers anticipated would be the greatest aviation event yet held in the United States. Attendees would include the most famous members of the flying world: airplane designer Glenn Curtiss, future manufacturer Glenn Martin, pilot Lincoln Beachey. Also in attendance would be Charles Broadwick and Tiny, who had moved west the year before.

On opening day, Tiny ascended with a hot-air balloon and did a double parachute drop, descending partway with one parachute, then cutting away from it, opening a second, and completing her descent. Glenn Curtiss expressed disapproval of parachuting, telling a reporter that he instructed his pupils to never jump in the event of an emergency: “It’s much safer for an operator to remain in his seat.” Phil “Skyman” Parmelee added: “None of that parachute jumping for us aviators,” he told the Los Angeles Times; “it’s too dangerous.” (A few months later, Parmelee’s biplane would flip in high winds, and he would die at age 25.) These sentiments were not surprising. At the time, no one had attempted to jump from an airplane. (The first such jump would be made two months later, when Albert Berry leapt from Tony Jannus’ flimsy Benoist 1,500 feet over St. Louis, Missouri.)

At the Dominguez Field meet, shrewd businessman Glenn Martin took notice of Broadwick’s “coatpack” parachute—with media darling Tiny as its demonstrator. The following year, Martin garnered headlines and world records for Tiny. In June 1913, he dropped Tiny from his biplane over Griffith Park in Los Angeles, and two months later, he dropped her from a hydroplane over Lake Michigan. Wearing Broadwick’s coatpack, she became the first woman to parachute from an airplane, and the first person to parachute from a hydroplane.

Martin and Broadwick apparently reached a curious agreement about the coatpack. Accounts vary, but newspapers repeatedly report that the device had been invented by Martin. A 1914 Los Angeles Times article about “Martin’s Life-Vest” says: “Although the life vest is…[Martin’s] own invention, the actual construction was done by Charles Broadwick, an old balloonist, under Martin’s direction.” Broadwick seemed to acquiesce, telling the San Diego Union in 1914: “I have spent many years of my life, giving up my time and pleasure to help Mr. Martin develop the parachute to the stage where we have it today.”

At most, Martin took Broadwick’s design and slightly tweaked it for suitability to the airplane. Taking credit for the invention of the packed parachute was shameless, but Martin went further: In March 1914, he applied for a patent for Broadwick’s device.

Over the years Martin held to his claim. A 1946 Martin Company newsletter gushed that he had invented the packed parachute and—oddly—the “first free-fall parachute.” In a 1927 deposition, Broadwick finally took credit, saying, “It was my own invention” and that Martin’s claim was “simply an advertising matter.” Tiny later verified this, telling an interviewer for the Columbia University Oral History Department that when they all first met, Martin “knew nothing about parachutes.”

But Broadwick apparently did not let the Martin arrangement sour him. Still cutting a handsome figure, he entertained the West Coast ladies. He was a real “sheik,” Tiny reminisced years later in Getting off the Ground by George Vecsey and George C. Dade, a book about pioneer aeronauts. “He was a fine-looking man. He’d go out and pick out the best-looking women and take ’em out to dinner. That was his excitement, aside from working with the [parachutes]. I’ve seen him take four beautiful women into the Ship’s Café, down in Venice.” As for Tiny, she had married a young seaman in 1912.

As the Great War loomed in Europe, Broadwick offered a nobler use for his coatpack.

At about nine pounds, the pack was now lighter, smaller, and better suited to snug cockpits. In a series of demonstrations between early 1914 and early 1915 at North Island in San Diego, Charles and Tiny wowed pilots, generals, Congressmen, and reporters with this “life preserver of the air,” as it came to be called.

At first, the idea of using the device to save airmen’s lives received consistent, albeit faint, praise. The Army even purchased two Broadwick packs for further testing—but they ended up on a shelf until after the war.

Pilots weren’t eager to adopt a parachute either. They argued that carrying one showed a lack of trust in one’s machine and in one’s flying ability. Army brass arguments wavered between two conflicting fears: that the presence of parachutes would make pilots abandon their machines needlessly, and that current parachutes weren’t reliable enough in all situations.

True, the static-line parachute was not ideal for all cases of airplane failure. If the craft were plummeting, the parachutist tethered to it could never break free. But that was no reason for wholesale rejection of the device. In 1916, another parachute showman-turned-inventor, Leo Stevens, had offered the Army his pack, which featured a ripcord that the jumper could pull to deploy the chute, ensuring the pilot could free himself from a falling airplane. But the Army, deeming it “dangerous” for inexperienced jumpers, turned it down as well.

In those days, fires in airplanes were common—so common that, in fear of a fiery end, some pilots carried pistols to commit suicide; others chose to jump to a quick death. If a pilot had Broadwick’s static-line parachute, however, he might have a chance at escaping a burning airplane.

What finally convinced the Allies of the utility of carrying parachutes in airplanes? The enemy. German aircraft had primitive static-line-operated packs, and when the airplanes caught fire, the pilots jumped out and parachuted safely to the ground. Seeing the benefits first-hand, Allied pilots came around, but the brass continued to hesitate. By the time they came around as well, the war was over.

Broadwick’s coatpack did figure prominently in the development of the parachute immediately after World War I. A group of civilians under the direction of Major E.L. Hoffman gathered all the parachute models they could get their hands on and set out to find the perfect compromise. Former Broadwick protégé Leslie Irvin was a key player, as was another former California acquaintance, Floyd Smith. In the end, the group took three elements—Broadwick’s coatpack, Stevens’ ripcord, and a pilot chute (a small canopy that opens to draw out the main canopy)—and created Airplane Parachute Type-A. Successfully tested by Irvin, the parachute was put into production. Irvin chutes saved countless lives, including that of young airmail pilot Charles Lindbergh.

By this time, Broadwick, who had parted ways with Tiny and remained in California throughout the war, had found love again. A young would-be actress who enjoyed the thrill of the air, Ethel Knutsen married the much older Broadwick and began jumping from airplanes.

On February 12, 1920, Ethel was testing one of her husband’s new parachutes over San Francisco. As a movie camera in another airplane recorded the scene, the suspension lines of Ethel’s parachute tangled, and she plummeted 2,000 feet to Marina Aviation Field. She died hours later.

Following Ethel’s death, Broadwick seemed to age dramatically. Years of broken bones, the deaths of his beloved Maude and Ethel—the misfortunes had taken a toll. Photographs show a changed man.

In the late 1920s, Broadwick made national headlines when pilot “Mickey” McKeon tested two of the inventor’s patented “planechutes,” designed to bring down a disabled or fog-enveloped aircraft. The tests were only partly successful. Broadwick continued to tinker in his San Francisco workshop, but by 1940 he was officially retired.

In 1942, he was admitted to the hospital, and the following year he died of heart disease. He did not die a rich man, or a celebrated one, and he seems to have died alone—family ties long broken, no pretty young companion by his side.

Forgotten for decades, Tiny found renewed fame in old age. In 1964, she donated an original Broadwick coatpack to the Smithsonian Institution. Due to its fragile condition, it is now kept in a climate-controlled storage unit in Suitland, Maryland. The other two existing coatpacks reside in North Carolina: one at the state’s Museum of History in Raleigh, the other with Tiny’s family. Credited with more than 1,100 jumps, Tiny died in 1978.

How are Broadwick’s contributions remembered today? Peter Hearn, author of five books on parachuting history, describes Broadwick as “one of those leading pioneers who used practical experience and technical expertise, rather than scientific qualification, to advance the development of a life-saving parachute.” Hearn also believes Broadwick deserves some credit for pioneering static-line chute deployment.

The U.S. Parachute Association’s executive director, Ed Scott, says that “just about all modern parachute systems” retain Broadwick’s chief innovation: “an integrated, form-fitting harness and container system nestled on the back.” Static-line deployment is still used by some novices making their first jumps, to ensure that the chute will open, but experienced parachutists today deploy a folded pilot chute that inflates and then extracts the main canopy.

As for the written record, Tiny has been memorialized in numerous books and magazines, but Charles’ name is fading. You’ll see a few parachute patents citing a Broadwick design, and aviation histories will briefly mention his invention of the backpack parachute. But what you won’t find in any of those documents is the complex tale of the man who spent a lifetime perfecting a life preserver of the air.

Lisa Ritter became interested in Charles Broadwick when she discovered that he boarded with her great, great aunt in San Francisco in the 1920s. She is currently writing a book about him.