Tales of the Old, Bold Pilots

In Oceanside, California, veteran fliers swap stories over breakfast.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/28/70280b8c-fa37-4ccf-8dce-c367269afe21/oldboldpilots-1100.jpg)

At the Oceanside, California Denny’s restaurant, the waitress greets a steady stream of guests by first name. Nobody asks for a menu, or needs one. One man, in his 90s and wearing a cowboy hat, shows another elderly man a new cane. They quietly discuss how it helps him get around with a bad hip. Later today I’ll struggle to match this soft-spoken, frail gentleman with the photo I find online, of a young pilot who shot down five Japanese warplanes in 70 minutes. In my mind, I’ll be matching faded black-and-white pictures with firm handshakes and crinkling smiles for some time. It’s Wednesday morning and southern California’s Old Bold Pilots Association is having breakfast at Denny’s.

The weekly tradition began in the mid-1980s with four former P-47 pilots, just an excuse for World War II aviators to get together and shoot the bull over a hearty breakfast. There’s never been a mission statement, or dues, for that matter. Nor do they host any “boring speakers.” But the roster now tops 330 names. On any given Wednesday, between 50 and 70 show up in Oceanside, some drop-ins from around the country and even across the sea. OBPA spokesman Tommy Head is one of the Vietnam generation assuming leadership of the group as the World War II numbers decline. Head was a photographer on F-105F reconnaissance missions out of Thailand and came back needing to talk. At his very first Old Bold breakfast, in 2003, he felt he could open up. “Meeting these World War II guys, I could finally talk about it,” he says. “I could get it off my chest. Man, I had nightmares for years after Vietnam. But somehow, just talking to these guys, I feel relieved.”

Historian Heather Steele’s World War II History Project website reflects the prodigious research she’s conducted for several books in progress, the first about a B-24 gunner shot down over France. In addition to tracking the history of fliers across Europe, Steele spent three years interviewing members of the Oceanside OBPA. “It was because I got to know the Old Bolds and loved them and wanted to honor them that I was inspired to write about this in the first place,” she tells me. “For me, it’s all about imagining these guys as young men and how they proudly volunteered and served. It’s about imagining a different time in this country.”

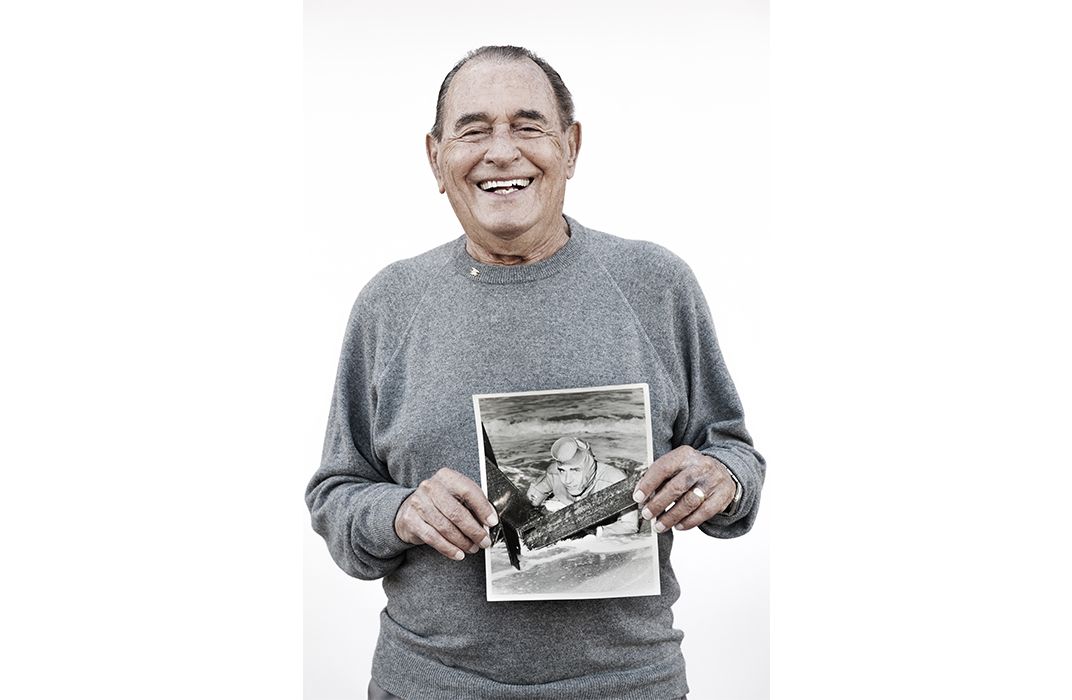

Willis “Bill” Hardy earned the title. You become an “Ace in a Day” by waking up in the morning with none and scoring at least five verified kills by midnight. During World War II, only 68 pilots qualified. Hardy was an F6F Hellcat section leader based on the aircraft carrier Hornet with no shootdowns to his credit the day the Japanese launched Kikusui, a massive kamikaze effort to destroy U.S. ships off Okinawa. “They sent down everything they could get in the air and every pilot that knew how to fly,” he says. “They didn’t need to know how to land.”

Late that afternoon, Hardy and his wingman caught two Zeros heading north, back to Japan. “They had led a bunch of kamikazes down and turned them loose on us,” he says. “They weren’t paying much attention now.” Hardy and his wingman slipped in unobserved behind them. “We gave each one a little squirt and watched them go in.”

Almost immediately afterward, they encountered four Aichi D3A “Val” suicide-bombers seeking kamikaze opportunities. Each of the Hellcats scored two. Daylight was fading fast when they received a report of a pair of Suisei “Judy” suicide-bombers menacing a radar picket ship. “The Judys had been modified to carry a 2,000-pound naval torpedo warhead underneath,” Hardy says. He soon got an extreme close-up. After flaming the first Judy head-on, “I got him burning, but the gunner in the rear seat had a big 20-mm cannon and kept shooting at me.” For cover, Hardy tucked the Hellcat under the flaming Judy “as close as I could get underneath without cutting my prop into him,” he says. Now below the arc of the cannon protruding from the rear gunner’s position, “I sat there looking up at this very large shape bolted under the airplane. It seemed like an hour, but it was probably only a few minutes.” As the Judy became engulfed in fire, “pretty soon the cannon wasn’t poking out anymore,” Hardy says. “It was pointing straight up.” He pulled out from underneath and held position on the dive bomber’s wing as the pilot tried to bail out and the incinerated airplane dove into the Pacific.

Now in darkness and with only one gun operative, Hardy engaged the remaining Judy, then circling a destroyer. He attacked, his last remaining round hitting the suicide-bomber’s fuel tank. His one-day tally was now five. For an encore, he flew back to the darkened Hornet—maintaining complete radio silence—and made his first and only nighttime carrier landing.

***

The second time Bill Weaver thought about dying that day in 1966 was when the rancher airlifting him to a hospital dangerously redlined his small helicopter. Weaver never trusted choppers. “Too many moving parts,” he says. The first time—just moments before—was after his SR-71 Blackbird, flying at more than three times the speed of sound, disintegrated, rendering him unconscious. When he came to, he was free-falling dreamlike from 78,000 feet as fragments of the shattered Blackbird dispersed over a path 15 miles long. “I thought, I must be dead,” he says.

As a Lockheed civilian test pilot flying out of Edwards Air Force Base in California, Weaver and Jim Zwayer, a recon and navigation specialist, were testing navigation and reconnisance systems in the iconic 1960s spyplane. At Mach 3.2 over the New Mexico-Texas border, the right engine experienced an “inlet unstart,” instantaneously creating a catastrophic thrust imbalance. The airplane pitched up violently. Weaver forced the stick forward and hard left, then prepared for the worst. “I knew what was gonna happen,” he says. He tried to warn Zwayer on the intercom, but double-digit Gs strangled his voice and pulled the blood from his brain.

Consciousness returned in mid-air. “I couldn’t figure out how I had gotten out of the aircraft,” Weaver says. “I knew I hadn’t activated the ejection system.” Though he couldn’t see it through his ice-coated faceplate, the small drogue parachute attached to his pack deployed and stabilized his plunge through the high-altitude atmosphere. Meanwhile, he worried that the device that automatically pops the critical main chute at 15,000 feet required initiating the ejection sequence first—a detail he never got around to before blacking out.

“I had no idea how far I had fallen,” he recalls. As he thought about opening his iced-over faceplate, the main parachute deployed. Floating in the winter sky over a barren, high plateau, he was relieved to see Zwayer’s parachute bloom nearby. “Oh, that was a great feeling,” he says. “Because I realized we had both survived, somehow.”

Weaver soft-landed, scaring an enormous antelope from the brush and ending his first and only career parachute jump. Somehow in that remote location, a rancher spotted his descent and landed a two-seat Hughes helicopter nearby. While Weaver struggled with his pressure suit, the rancher choppered over to retrieve Jim Zwayer but returned with devastating news: Zwayer was dead. Weaver would later learn that Zwayer was killed instantly when the Blackbird disintegrated—his textbook parachute descent was entirely automated. Leaving his foreman to guard the body, the rancher provided Weaver a harrowing lift to a Tucumcari hospital, revving the little chopper past its airspeed limits as the meticulous test pilot eyed the instruments apprehensively.

The explanation for Weaver’s unassisted egress from the SR-71 became clear. The seatbelt and shoulder harness—nylon with a tensile strength of 5,000 pounds—dangled from his flightsuit, torn off where they attached to the ejection seat, which never left the aircraft. The supersonic blast during the breakup had literally ripped him out of the seat and clear of the cockpit, protected by his inflated pressure suit.

Bill Weaver spent 30 years at Lockheed, advancing to test the company’s L-1011 airliner. “I went from flying Mach 3 to Mach 0.9,” he laughs. Until recently, Weaver flew a modified L-1011 for Orbital Sciences, a private space venture, air-launching satellites on Pegasus rockets. He’s still involved with the company in an advisory role.

***

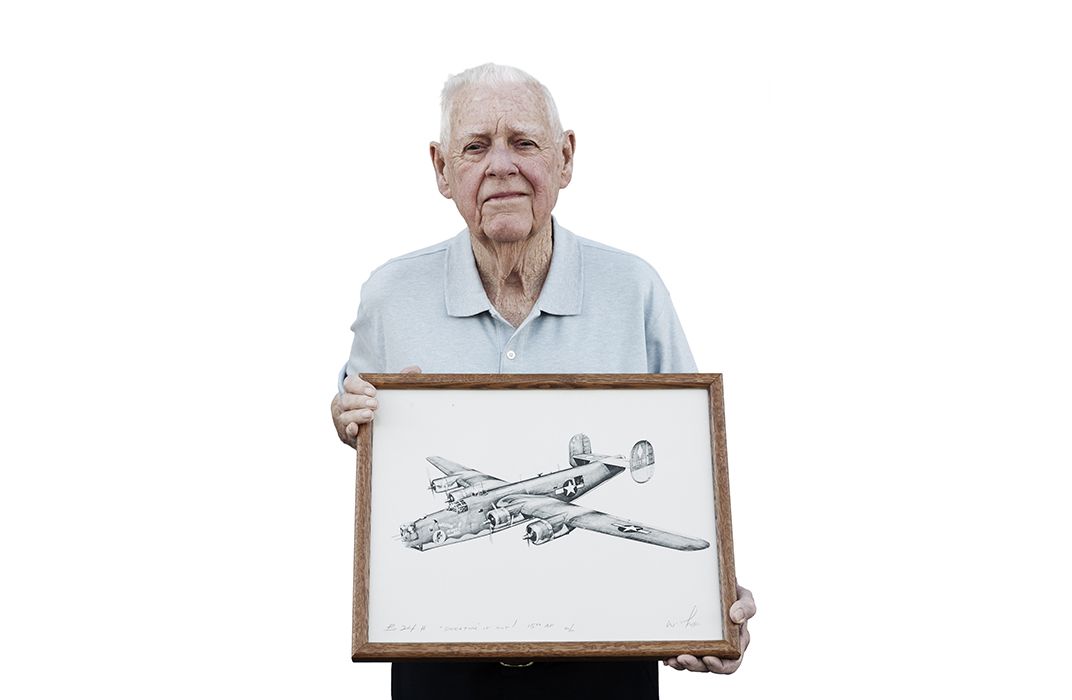

“Three times,” Rod Braswell tells me. “Three times to Ploesti.” The raids on the German oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania, resulted in the heaviest American aircraft losses in World War II. Begun with a catastrophic low-altitude attack on August 1, 1943, 53 of the 177 B-24s dispatched did not return. At 22, Braswell was one of the younger B-24 pilots flying Ploesti missions.

“Ultimately, ground fire was the biggest threat,” he says. “At first, we had no protection. We went in all by ourselves and the German fighters took out a lot of us.” Eventually, they got fighter escorts, including members of the Tuskegee Squadron.

“You fly 50 missions and they let you come home,” Braswell says. “You fly 49 and get scared and can’t fly number 50, they don’t let you come home. We got hit a helluva lot. I went through three airplanes.” Mission number 50 turned out to be his most harrowing. “My nose gunner was killed. The anti-aircraft shell went through the seat of his chair and exploded in his body. My navigator lost an eye.

“Let me tell you how uncomfortable it was. I have to wear a lot of clothes to keep warm so it’s hard to move. I have to wear an oxygen mask and the moisture I exhale freezes so I’ve got icicles on my neck. I have to wear a steel hat that crushes my ears—there were no pilot’s helmets in those days so they gave me a doughboy’s steel helmet to wear. I’ve got a flak suit on that has all the metal and canvas in the front but nothing in the back, so all the weight is on the front and it’s cutting my neck. And it’s freezing cold. And people are shooting at me.”

***

Alexander Poddoubnyi never aspired to fly the world’s largest airplane. Over the clamor of conversation and clinking coffee cups, he explains in a thick Russian accent: “When I was young, I want the fighter. Every young guy like me wants the fighter.” Poddoubnyi was in fact the youngest in his test pilot class in Moscow. But his mother was ill, so he was drawn back to Kiev, and a position at the Antonov Design Bureau—a career move considered less prestigious than the cockpit of a MiG. “Everybody thought I was stupid to switch to transport aircraft,” he says. A 20-year career as a test pilot for Antonov ensued with “certain successes.” Poddoubnyi was part of the cockpit crew on the first flight of the Antonov An-124 in December 1982. Weighing nearly 900,000 pounds and having a wing area of 6,700 square feet, the massive An-124 has set more than 30 world records, mostly weight- or distance-related, becoming the world weightlifting champion with a 377,000-pound payload.

How do you learn to fly the world’s largest airplane? By flying the world’s largest airplane, Poddoubnyi says. Due to lack of sophisticated simulators in the Soviet Union, “one hundred percent of our flight training had to be done in real conditions.” Still, the An-124 only looks intimidating; “it’s really very easy to fly,” he maintains. The fly-by-wire controls make it more pilot-friendly than many smaller “big” airplanes with conventional hydraulics, like the C-130 Hercules. In 10 years, Poddoubnyi accumulated about 10,000 hours in its five-person cockpit. With the thawing of the cold war, the mammoth began blotting out the sun in U.S. airspace too. “In 1988, we came in the -124 to New York to pick up aid for children of Chernobyl,” Poddoubnyi recalls. Soon, the pride of Soviet aviation was part of the ground display for enthusiastic capitalists at Oshkosh.

In the end, it was love that pulled Poddoubnyi from the cockpits of goliaths. “I flew the world’s largest airplane to the United States and met my future wife,” he explains. It was the new An-225 that he landed in Chicago. On a later flight, after frustrating passport delays caused by KGB meddling that separated him from his bride, Poddoubnyi executed Plan B: fly an An-124 to San Diego, park it, and defect to the United States in 1991.

***

“You mean, why am I here?” 90-year-old Rear Admiral Richard Lyon (Ret.) replies when I ask—with some hesitation—if he has any aviation experience. Lyon is the first Navy SEAL to attain the rank of admiral, not to mention a former two-term mayor of Oceanside, so no one’s going to question his credentials. Anyway, his résumé reads like a character sketch in an adventure novel. His World War II service with a Scouts and Raiders recon unit of Navy Special Forces led to intelligence missions traveling incognito through post-war China, shadowing the movements of Mao Tse Tung’s revolutionary forces for the commander of the Seventh Fleet. Accompanied only by an English-speaking Chinese national, “I didn’t look very Chinese,” he says today, “so I kept my head down a lot.”

After discharge Lyon began work on an MBA at Stanford, but was recalled during the Korean War to form the elite underwater demolition team UDT 5 at Coronado Naval Base in southern California. “I personally wound up well north of the 38th parallel inside Wonsan harbor doing mine discovery and disarming, plus recovering new mines we hadn’t seen before. My uniform was a drysuit and my armament was a pair of 24-inch bolt cutters.” In that pre-SCUBA era, Lyon free-dived in 36-degree North Korean waters to retrieve mines eight feet below the surface. Compared to the diving equipment available to later SEALs, “I was skinning it,” he says.

When Lyon retired in 1983, he was deputy chief of the Naval Reserve. As for that cockpit experience I asked about, he admits most of it was, you might say, unlogged. “My last tour of active duty as a rear admiral, I had a beautiful North American Sabreliner at my disposal,” he explains, “plus a pilot, copilot, and crew chief. Now, guess where I learned to fly?”

***

“The union wanted me gone,” Chuck Hosmer says. “I was 60 and didn’t want to go.” He’s a former American Airlines 777 captain, aged out of the left seat after 31 years. Commercial pilots, active and retired, are well represented on the OBPA roster. After a stint as an ex-pat pilot for Air India, Hosmer now works as a contractor for Citation, training pilots. One of the younger regulars at OBPA, he exudes the lean intensity of the pilot in command. While many of the bold and older feast on high-calorie breakfast combo plates, Hosmer orders a spartan bowl of oatmeal and trades terse insider talk about today’s commercial cockpit.

“My real heartache,” he says, “is aviation safety and where it’s headed.” Hosmer considers the June 2009 Air France 447 crash, in part attributed to inexperience and lack of cockpit communication, an inevitable result of how pilots are now trained. “You tell someone to intercept a course and the first thing they do is drop their head and start typing on a keyboard. They need to look out that window first and see what’s over there.” Getting even an interview at a major airline used to require a minimum of more than 2,000 hours of flight time, but with today’s new multi-crew license, candidates can qualify as commercial copilots in just 14 months of training with a minimum of flight hours—none of it solo. “They’ll give you a total of 12 landings in a real airplane—everything else is in simulators,” Hosmer says. “Then you walk out the door and you’re supposed to be qualified to sit in the right seat of a 737 and fly passengers. What you’re not qualified to do is go across the street and rent a Cessna 172 and fly alone. To me, that is just bizarre.”

He worries that the profession is losing its appeal to avid aviators, and becoming just another not-too-well-paid gig for people with no better option. In the cockpits where Chuck Hosmer and others around us put in thousands of hours, pilots practiced the skills required to be an airline captain and react capably in a crisis. “And that’s what we’re losing,” he says. “What we’re gaining are computer programmers.”

***

“I told them I didn’t care,” Charles Huebsch says. “I just wanted to fly a P-38.” This was his answer when asked “You do understand that a photo recon plane has no guns to defend itself?”

The Japanese called the aircraft “Photo Joe.” Huebsch’s recon flights targeted air bases in the south Pacific as well as troop emplacements, anti-aircraft batteries, and potential landing sites. “Soon as the smoke cleared, I was there taking pictures,” Huebsch says. “The bomber pilots would come back and say, ‘We wiped them out.’ Then we’d say, ‘Hey, look at our pictures. The damage was not complete.’ The bomber pilots just loved us.”

Low on fuel after photographing a large Japanese air base, Huebsch saw a glint on the island of Biak northwest of New Guinea. Once he realized what they had stumbled upon, he told his wingman he was going for the shots—low fuel or not. “I told him, ‘These pictures are too valuable. I’ll belly the thing in. I’ll lose the plane but I’ll get the shots. Search for me on the south side of New Guinea.’ ” It turned out to be a recon photo-thon. More than 100 Japanese Zeros and a number of Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers were laid out along an airstrip, like sunbathers under the cloudless Pacific sky. “Nobody even fired a shot,” he says. After the final shutter click, he flew as far as his fuel would take him, found an island with a hard coral beach—“about the length of the flight deck on the Midway”—and landed wheels-down instead of bellying in.

Local residents greeted him, fishing spears in hand. “All the ladies were dressed like early National Geographic,” Huebsch says. He established an uneasy rapport, and after five days, a search plane spotted his P-38 and dropped K-rations for Huebsch and the locals. He slept in the closed cockpit of his aircraft every night. “They taught us in jungle school: Don’t mingle with the natives.” Instead, he was soon spearfishing with his hosts, but wearing rolled-up shorts: “I was too embarrassed to go naked.” After days sampling the local cuisine of roots and grub worms, he was glad to see a World War I-vintage Australian amphibian that had landed near the beach. “We were only told to pick up your film,” the crew informed him. “We’ll be back for you in a couple of days.”

When they finally returned him to base, an MP was waiting to take him to the commander of the Fifth Air Force. “The general’s aide bawled me out. ‘Why didn’t you belly that plane in? You could have flipped over and killed yourself.’ He poured me a glass of straight whiskey. Well, I’ve been eating grub worms for days and I told him, Sir, I can’t drink this. ‘Don’t pour it out,’ he said, ‘that stuff’s too hard to get!’ ”

***

“We didn’t fight for the Nazis, we fought for Germany,” says Kurt Schulze, former Luftwaffe Oberleutnant and longtime OBPA regular. Now retired after a career in southern California real estate and banking, Schulze flew 23 bombing missions to England. As a young navigator in a blitzing Dornier Do-217 night bomber, he crossed the darkened English Channel, flying low to evade Britain’s rudimentary radar and night fighters. “Then came London,” he says somberly. “Balloons and searchlights and bombing. It was not a great pleasure. As you know, war is hell.”

His tenure as a navigator ended when Luftwaffe commander Hermann Goering ordered every available pilot into a fighter. Soon he was flying a Messerschmitt Bf 109G in the far north of Finland. After downing a Russian fighter, Schulze was swarmed by two others, and he crash-landed in the remote, frigid terrain. Rescued by German mountain troops and returned to his base at Petsamo, he was summoned by his commandant. “The old man put a bottle of booze on the table, and I was flying again that afternoon. He told me those were the two best things to overcome getting shot down.”

Answering an alarm one bright Sunday morning, Schulze arrived just in time to see the legendary Bismarck-class battleship Tirpitz capsize after being bombed by British Lancasters, which had fled the scene only moments before. Later, two training squadron commands fizzled as the Luftwaffe ran out of fuel, and he received the good news that he was assigned the JG-51 squadron in Gdansk, Poland. The bad news: The city was under siege and, as he landed, Russians were already shelling the airport. “We couldn’t even fly our planes back out. We had to load them on trucks and drive them,” he says, chuckling grimly. “By the time we reached Germany, I told myself, ‘The war is lost.’ ” He made his way to Norway and briefly led another squadron as the Third Reich collapsed.

Initially captured by British forces, Schulze was interrogated by an American Army Air Forces captain, “who put a pistol on the table and showed me photographs of the concentration camps—the first time I had seen anything like that.” He soon joined 700,000 German POWs held by the French. Two years later, he returned to Germany as a civilian, and in 1953 immigrated to the United States with his wife and son, pumping gas for a dollar an hour. Today at Old Bold breakfasts on misty Oceanside mornings, the lines between former adversaries have long since been dissolved by camaraderie. “These are all my good buddies,” Schulze says.

There’s nothing unusual about pilots getting together to gab about flying, Heather Steele reminds me. “But what’s unique about the Old Bold Pilots is that so many show up every week. And the way they look out for each other and care for each other. There’s a mutual respect not only for other Allied pilots but for the Luftwaffe pilots they flew against.” The demographics of the OBPA range from World War II pilots to a Korean War contingent to the not-so-old Vietnam vets. The World War II roster is declining dramatically. “So, if we as a nation want a chance to meet these guys and know them and honor them,” she says, “now is the time.”

That would be 7 a.m. every Wednesday at Denny’s.