How America’s First Banned Book Survived and Became an Anti-Authoritarian Icon

The Puritans outlawed Thomas Morton’s “New English Canaan” because it was critical of the society they were building in colonial New England

When the Puritans set sail for New England in 1630, they likened themselves to ancient Israelites settling in the promised land. Liberated from the Church of England, which they viewed as too Catholic, they sought to reform the church and establish a new Christian commonwealth guided by their covenant with God.

“We must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill,” John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, famously proclaimed on the journey over from England. “The eyes of all people are upon us, so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

Just seven years after the Puritans’ arrival, an Anglican lawyer named Thomas Morton published a book that threatened the young colony and its residents’ covenant with God. New English Canaan, a three-part text published in Amsterdam in 1637, is mostly filled with detailed observations about the region’s Indigenous people and descriptions of plants, animals and natural resources that could be commodified by white settlers. But a brief section at the end offers a withering critique of the Puritans and the society they were building, including their treatment of Native Americans.

Members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—known to be a tightly controlled society—adhered to strict beliefs about how to live and worship. Women and children were taught to read so they could learn directly from the Bible, but few other books were imported. Public entertainment wasn’t allowed except for church services. Cursing was punishable by law. Despite harsh winters and conflicts with Native Americans, the Puritans believed their colony would survive if they obeyed God, and they were constantly on the lookout for signs from above.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/92/b59280c6-0d29-4ba8-a282-0509944f3f85/screenshot_2023-09-26_at_40158_pm.png)

Shortly after New English Canaan’s publication, the Puritans outlawed the text in their colonies, committing what historians consider the first act of book banning in the present-day United States. Fewer than 25 of the original copies from Amsterdam survive today, but far from disappearing, the book has cropped up continuously over the last four centuries in other works of literature and history. And Morton, who was once ridiculed by other colonists and nicknamed the “lord of misrule” by Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford, became an anti-authoritarian symbol celebrated for his defiance of Puritan society.

Sarah Rivett, a literary scholar at Princeton University who has occasionally taught the book in her classes, says it’s hard to draw a direct line from the banning of New English Canaan to modern book bans due to differing cultural contexts. Still, she says the book’s long life is telling.

“That’s why we read these texts at all—to think about how things play out over time,” she explains. “Why they’re dangerous is the thing that is culturally specific and maybe can’t be connected, but the belief in the power of books to change people’s minds, to cause people to behave in a certain way, and to generate a movement or bring a group of people together, that is a question that’s relevant today.”

Morton was born into an upper-class family in England around 1579 and later worked as a lawyer. After he married a wealthy widow, his new stepson took him to court over the considerable estate left by her first husband. As that fight wore on, Morton befriended the colonist Ferdinando Gorges, who would later go on to found Maine. Abandoning the drawn-out court proceedings, Morton traveled to North America at Gorges’ behest in the early 1620s. There, he began a quest to establish his own colony.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/2b/242b19c5-9b92-4ed6-bba2-750642b5c041/maypole_at_merrymount.jpeg)

While another English settler, Captain Richard Wollaston, was away in Virginia, Morton usurped his colony, Mount Wollaston, and created a new utopian colony, Mount Ma-re (later known as Merrymount, in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts). In his New England society—in contrast to the strict Puritan settlements—colonists and Native Americans mingled, no hierarchies or forms of leadership existed, and all religious beliefs were tolerated, from Indigenous spiritual beliefs to English pagan beliefs to Morton’s own Anglicanism.

In 1627, Morton constructed a maypole in the town square and invited anyone to join him in drinking and dancing around the pole. This incited his Puritan neighbors, who were already fed up with him for trading guns to Native Americans. When Morton repeated the event the following year, Bradford ordered his arrest.

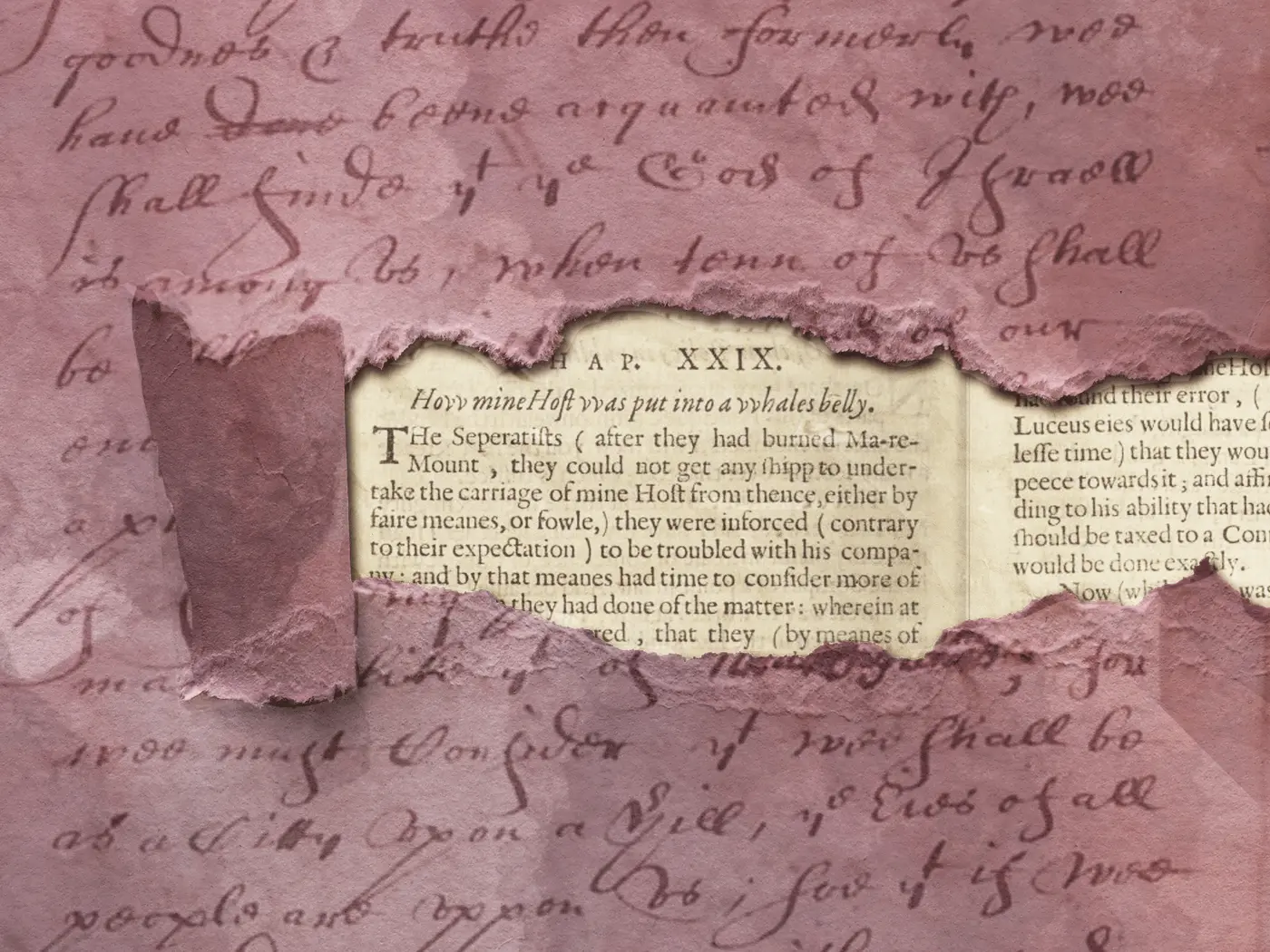

Recounting the scene in New English Canaan, Morton wrote, “The Separatists, envying the prosperity and hope of the plantation at Ma-re Mount (which they perceived began to come forward and to be in a good way for gain in the beaver trade), conspired against mine host”— Morton’s nickname for himself—“especially … and made up a party against him and mustered up what aid they could, accounting of him as of a great monster.”

Morton was subsequently exiled to an island off the coast of Maine, where he was picked up by an English ship and taken back to his home country. By the time he returned to New England the following year, his maypole had been chopped down to use as firewood, and Merrymount’s supplies had been raided.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/bb/42bb566a-edb0-4327-8f0c-808fa59f3af1/screenshot_2023-09-27_at_14950_pm.png)

In 1633, Morton attempted to publish the first edition of New English Canaan in England, but the printing was stopped by “agents for those of Newe-England,” according to a petition written by a contemporary bookseller. Four years later, he succeeded in publishing the text in Amsterdam. English officials attempted to seize all copies entering the realm, but Morton’s book made its way to New England anyway.

Morton viewed the Puritans with as much vitriol as they did him. In the early 1630s, he sued the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plymouth Colony in an attempt to revoke their charters. These documents become the basis for New English Canaan. In the final part of the book, Morton chastises the Puritans for their harsh treatment of Native Americans and what he sees as the hypocrisy of their beliefs. He includes a telling poem in his account:

What! Is their zeale for blood like Cyrus thirst?

Will they be over head and eares a curst?

A cruell way to found a church on! noe,

T’is not their zeale but fury blinds them soe

In another passage, Morton writes about the Puritans “despoiling” the grave of a Native American leader’s mother and the tragedy that had befallen his tribe: “It was a dying race, and what little courage the pestilence had left them was effectually and forever crushed out by Myles Standish, when at Wessagusset, in April 1623, he put to death seven of the strongest and boldest of their few remaining men.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/01/f50156ab-f8e1-460e-be51-f0a664fbb178/screenshot_2023-09-27_at_21515_pm.png)

Historian Peter Mancall, author of The Trials of Thomas Morton: An Anglican Lawyer, His Puritan Foes and the Battle for a New England, describes New English Canaan as “not very long” and “not very well written,” but with immense value in what it says about the nation’s founding.

“One of the expected stories we have for early New England is that Native peoples were living there and [the Puritans], these religious zealots, or heroes, depending on your perspective, … come over and there’s this unfolding of what is either the grand spectacle of the beginning of so-called American history or one of the great tragedies of the displacement of Indigenous peoples,” he says. “Both of those stories have a certain inevitability about them. What I saw in Thomas Morton was someone who I thought made that story much more complicated.”

Morton himself wasn’t a completely sympathetic character. Mancall believes he was “probably fairly obnoxious”—referring to himself as “mine host” and giving his Puritan enemies nicknames such as “Captain Shrimp,” his moniker for Standish. And while he wrote about Native Americans in a much more humanizing way than some at the time, arguing that they “lead [a] more happy and freer life” than many Christians, he was also colonizing their land, describing them as “savages” and comparing them to “the wild Irish.”

Today, many Americans know the story of the Puritans and the Pilgrims—who came to New England ten years earlier, in 1620—as one of clear and inevitable victory that eventually helped establish the U.S. But, as Mancall explains, the Puritans’ crackdown on New English Canaan shows how uncertain and anxiety-ridden they actually were at the time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/f7/52f7a2ab-5975-4178-a3c0-8aa985c11d32/screenshot_2023-09-27_at_22254_pm.png)

“They cross the Atlantic Ocean not knowing if they’re going to succeed, and they see everything as the working out of a divine plan,” Mancall says. “It’s hard for us now in the 21st century to go back to those early decades of the 17th century, when they’re cracking down on these things. [Was it] because they were just thin-skinned? Or are they cracking down on people like Morton because they thought this was a test posed by God—their God who’s waiting to see how they respond.”

Morton was exiled from the colonies on three separate occasions, but he returned each time and eventually died in Maine around 1647. During his lifetime and for decades after, his book was likely not read widely, and depictions of Morton by other writers were largely comedic. Then, some 200 years after New English Canaan was published, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a short story titled “The Maypole of Merry Mount.” The work is “a meditation on the danger of ‘merriment’ out of control, a lament for the loss of Merry Old England and a prophecy of the triumph of Puritanic gloom,” wrote William Heath for the Nathaniel Hawthorne Review in 2007. While Morton isn’t named in the story, scholars have little doubt the tale, which centers on a free-spirited newlywed couple who dance around a maypole that is subsequently cut down by the Puritans, is based on his short-lived colony.

Hawthorne’s story appeared at a time of growing criticism of Puritanism by American intellectuals, according to Mancall. Public thinkers were also interested in the history of early America, and New English Canaan offered a trove of knowledge with its descriptions of the land, trading between colonists and Native Americans, and early governance in the colonies.

In 1883, a Boston publisher released a new edition of Morton’s book, with an introduction and notes written by Charles Francis Adams Jr., a descendant of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams. (A digitized version of the 19th-century volume is available via the Smithsonian Libraries.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/04/010438ff-d2d8-4a26-9289-8789f34a3d49/screenshot-2023-09-27-at-15303-pm.jpg)

Adams found “the book so strange … that he enlists all of these scholars to explain the references,” Mancall says. “So then Morton’s book, divorced from its political context, … becomes a sort of artifact of scientific knowledge that people can use to understand early New England.”

In the 20th century, New English Canaan took on yet another life, becoming a symbol for anti-Puritanism and, later, anti-authoritarianism more broadly. In his 1925 book In the American Grain, poet William Carlos Williams wrote that the Puritans’ reaction to Morton’s maypole revealed their nature: “Trustless of humane experience, not knowing what to think, they went mad, lost all direction.” A decade later, Morton appeared in Stephen Vincent Benét’s short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” sitting on a jury of the damned for a man who sells his soul in exchange for prosperity.

New English Canaan became even more popular in literary circles in the 1960s and 1970s, during the counterculture movement, and the book started being taken more seriously as a piece of literature instead of just history.

“Because [Morton] is a rebel—and rebels are always cool to study—you do see Morton being read by scholars of American literature going back to the 1970s at least, and probably even [earlier],” says Rivett, “trying to grapple with the text on literary terms, thinking about how he’s using classical references, how he’s using allegory and biblical references to achieve some of his goals, whether they’re polemical or ideological.”

Morton really got his due in 2001, when Philip Roth, in his novel The Dying Animal, wrote, “Our earliest American heroes were Morton’s oppressors: [John] Endecott, Bradford, Myles Standish. Merry Mount’s been expunged from the official version because it’s the story not of a virtuous utopia but of a utopia of candor. Yet it’s Morton whose face should be carved in Mount Rushmore.”

New English Canaan was never blotted from history as the Puritans intended. To this day, it challenges Americans’ perceptions of the founding of the country.

Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, director of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, specializes in rare books and book history. But long before she knew she wanted to be a librarian, she encountered New English Canaan and Morton, whom she considers a “free spirit.”

“When I was younger, I was fixated on maypoles … because I had a nursery rhyme book that had people dancing around a maypole,” she says. “I decided to do a report [on them] and then came across this book. … It was the first thing that actually challenged my view of the [Puritans].”

“To allow a group of people or any individual, no matter how powerful or loud, to become the decision-maker about what books we can read or whether libraries exist, is to place all of our rights and liberties in jeopardy.” OIF Director Deborah Caldwell-Stone https://t.co/nTg2boF7fW

— ALA OIF (@OIF) September 20, 2023

Today, with stories of book bans in schools and public libraries dominating the headlines, New English Canaan holds new relevance. Evangelestia-Dougherty, who has studied banned books throughout history, says all bans have one thing in common: fear.

Banned books say a lot about American society at a given time, whether it’s the censorship of The Canterbury Tales under the 1873 Comstock Act, which criminalized sending “obscene, lewd or lascivious” materials through the mail, or the 1977 banning of James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room for its portrayal of queerness.

As Evangelestia-Dougherty says, “It’s always about someone feeling that their idea should be promoted over someone else’s, that there is a right way to live, there are the right people to be with or the right things to say.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/colleenc.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/colleenc.png)