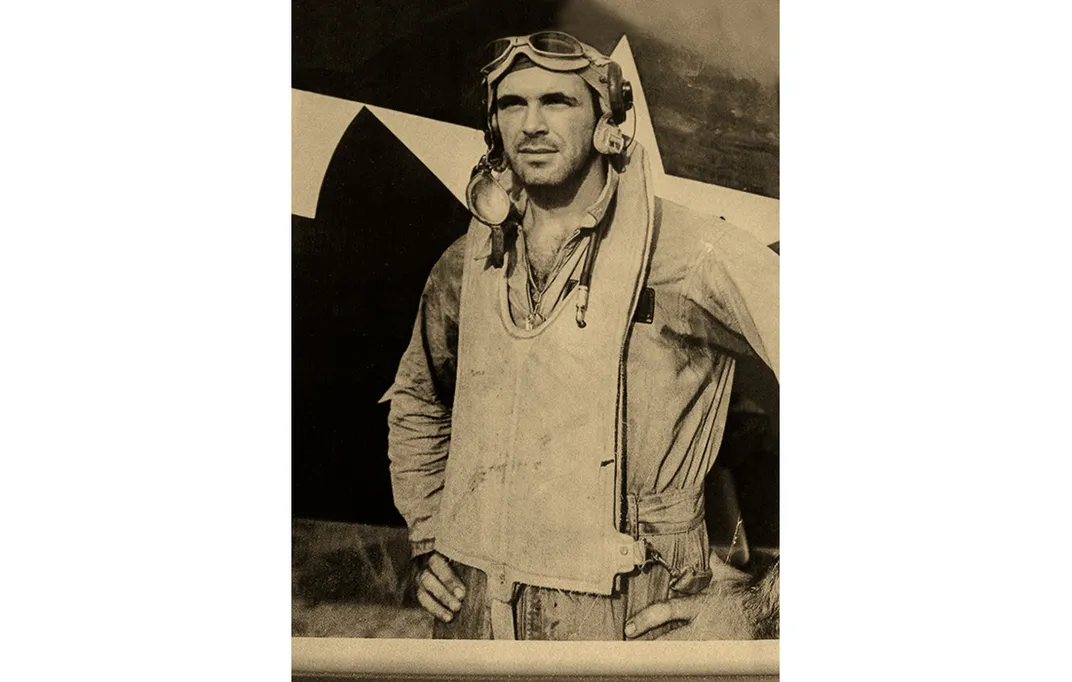

Corsair vs. Kamikaze in 1945

Above and Beyond

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/49/1b49e049-e00c-4920-844d-e34ce789116b/17b_aug14_-1d_vmf-222_live.jpg)

During World War II, it was my honor to fly F4U Corsairs with the Marine Corps (VMF 222, MAG-14) in the vicinity of the Solomon, Philippine, and Ryukyu islands, from Yontan Airfield on Okinawa. One day in 1945, when I was on combat air patrol with my wingman over Buckner Bay off the southern coast of Okinawa, one of our carriers, the USS Franklin, took a direct hit from a kamikaze. Then a second unidentified aircraft was reported entering the area. A few minutes later, I spotted a Zero flying very low over the water.

I pushed the stick forward, dove, and got on his tail, only 20 feet above the ocean at 300 mph—not the Corsair’s top speed, but pushing it for the Zero. The Corsair was equipped with six Browning machine guns, and I opened fire. The Zero banked left sharply to avoid my fire. I was only 100 feet behind him, and just as I started to bank to stay with him, his wingtip touched the water and the Zero cartwheeled, wing over wing, and crashed into the sea. At the speed we were flying, hitting the water must have been like hitting a brick wall. Before the pilot could get out, the Zero sank.

As I pulled the stick back to regain altitude, I felt two thuds, and realized I had been hit by friendly fire from our own naval anti-aircraft guns. The Corsair was like a seasoned prizefighter who could take punches on the chin and refuse to go down. On many of our fighter sweeps and low-level bombing runs, our airplanes would get hit repeatedly by Japanese anti-aircraft fire, but somehow always get us back to our bases. But this time I knew I was in serious trouble.

I discovered that my hydraulic pressure was down to zero, so it would be impossible to lower the landing gear and wing flaps for a normal landing. I called Yontan and asked to come in for a wheels-up crash landing, but I was told that attempting that while loaded with live ammunition and fuel would in all likelihood end in an explosion. Air Command eventually determined that my best option would be a water landing.

There was only one problem: I was terrified of ditching. I was the world’s worst swimmer. Back in flight school, I almost washed out because I couldn’t pass the swimming test. We had to swim across a pool, pull ourselves out of the water by a rope, and swim a short stretch under flames. I told the instructor I couldn’t swim well enough to do that. Just try your best, he said.

On the day of the test, the pool was crowded with guys. I knew I couldn’t make it, so after staring at the water for a while, I quietly walked to the far end of the pool, sat down near the instructor, then slipped into the water. After a few seconds he noticed me at his feet and said, “Miller, good job. I didn’t think you’d make it.”

But there was no way to cheat the Pacific. And I had heard that sharks were common in these waters.

I was vectored to a spot about two miles south of Buckner Bay. Most pilots—if they’re lucky—don’t have much experience in crashing airplanes. I did. Back in 1943, when I checked in at Naval Air Station Glenview in Illinois for my primary training, I was told I would fly the N3N, the Naval Aircraft Factory biplane. The N3N, which looked like a Stearman, was the most stable airplane in the Navy, they told me, and virtually impossible to crack up.

About halfway through our stay at Glenview, we were doing simulated carrier landings. An auxiliary field had a large white circle—the simulated carrier—painted on a runway. For a week, we practiced making touch-and-go landings in the circle. At the end of the week we had to make five passes at the circle, touching our tires at least three times. In my first four attempts, I touched the circle twice. Coming around for my fifth and crucial attempt, I realized I was about 35 feet too high. I tried desperately to slow down and lose a little altitude. Apparently I slowed down too much, because all of a sudden, I stalled out, and the big biplane dropped like a broken elevator. At least I crashed at dead center of the circle.

The wheel struts were driven right up through the wings and the propeller was in the ground. I was a little stunned, but I didn’t seem to have a scratch on me. I heard sirens, and looked up to see emergency vehicles speeding in my direction with red lights flashing—ambulance, fire engine, a crash crew, a crane. Apparently they thought they were going to have to pick me up with a shovel.

Anyone who had been involved in an accident had to appear before the Accident Review Committee, which would determine if the accident was pilot error or mechanical failure. If it was pilot error, the cadet automatically washed out of flight school. I felt there was no question the crash was caused by pilot error—mine.

My instructor, a Marine Corps captain who had recently returned from battles at Wake and Midway islands, told me he was going to attend the hearing with me. When we walked into the hearing room, it was like the court-martial scene in The Caine Mutiny. The six members of the accident review committee, all senior naval officers, were seated at an elevated table. My instructor and I were told to sit at a lower level, which succeeded in making us feel inferior.

The chairman called the meeting to order. “Cadet Miller, would you care to make a statement explaining your version of the accident?”

“I came in a little high while making a simulated carrier landing. I slowed the plane down to lose a little altitude. I stalled out and crashed.”

“Well, that’s all rather obvious,” the chairman said. Then he started whispering to the other members of the committee. I was dead certain they were all set to wash me out.

At that moment my instructor, who undoubtedly had more actual combat experience than the six members of the committee put together, asked permission to say a few words on my behalf. “Look, we asked the kid to hit that circle three out of five times, and goddamnit, he did exactly what we asked him to do,” he said.

The committee was a little stunned. The members started whispering again. Finally the chairman said, “It is the decision of the accident review committee to have Cadet Miller retested for simulated carrier landings.” I was retested and managed to pass without destroying any more N3Ns.

But now, as I skimmed over the Pacific south of Buckner Bay, my Corsair was damaged and my instructor was not there with me.

As it turned out, the sea was extremely calm, so my landing was easy. I came in with the nose up, then let the tail skim the water first, creating enough drag to lower the belly until it was in the water. I finally came to a stop. It was then that I broke the world’s speed record for getting out of a cockpit and onto the wingtip, where I inflated my Mae West, said a quick prayer, and slid into the Pacific. Bobbing in the ocean, I dog-paddled away from my beautiful Corsair, then watched it sink, thinking, There goes $100,000 worth of sophisticated military aircraft.

Several ships in the immediate area had watched me go down. Within 20 minutes—which felt like 20 hours—a minesweeper lowered a dinghy and picked me up.

The dinghy took me to the dock at Naha on Okinawa, where I was rushed to the Navy hospital for a thorough physical exam. My squadron knew I had gone down, and were all happy to see me in one piece. For that mission, I was promoted to the rank of captain and received my second Distinguished Flying Cross.