Monster Bomber

At the Pima Air and Space Museum, the B-36 is the largest U.S. warplane ever rebuilt

The Editors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Monster_Bomber_FLASH_AUG2010.jpg)

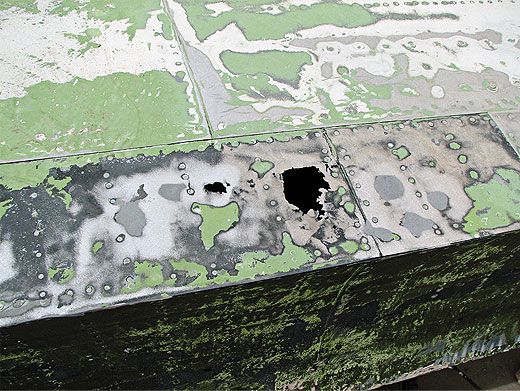

It was the end of the line. Convair B-36 Peacemaker 52-2827, later named the City of Fort Worth, was the 383rd of 383. The nuclear bombers, designed for use in World War II but not finished in time, were intended for transatlantic strikes against Germany. With a range of 6,000 miles and a bomb payload of up to 86,000 pounds, they were built huge—the wing spanned 230 feet, and had almost three times the area of a B-29’s. B-36s served from 1948 to 1959. After retirement, 52-2827 was sent to Fort Worth, Texas, where over the years it was besieged by weather and vandals. In 2005, the Air Force reallocated it to Tucson, Arizona’s Pima Air & Space Museum, which spent four years restoring it, a job that required, among other things, 5,000 nuts and bolts and 3,000 rivets.

For more photos of the B-36, see the gallery at left.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.