Mountain Training for Helicopter Pilots

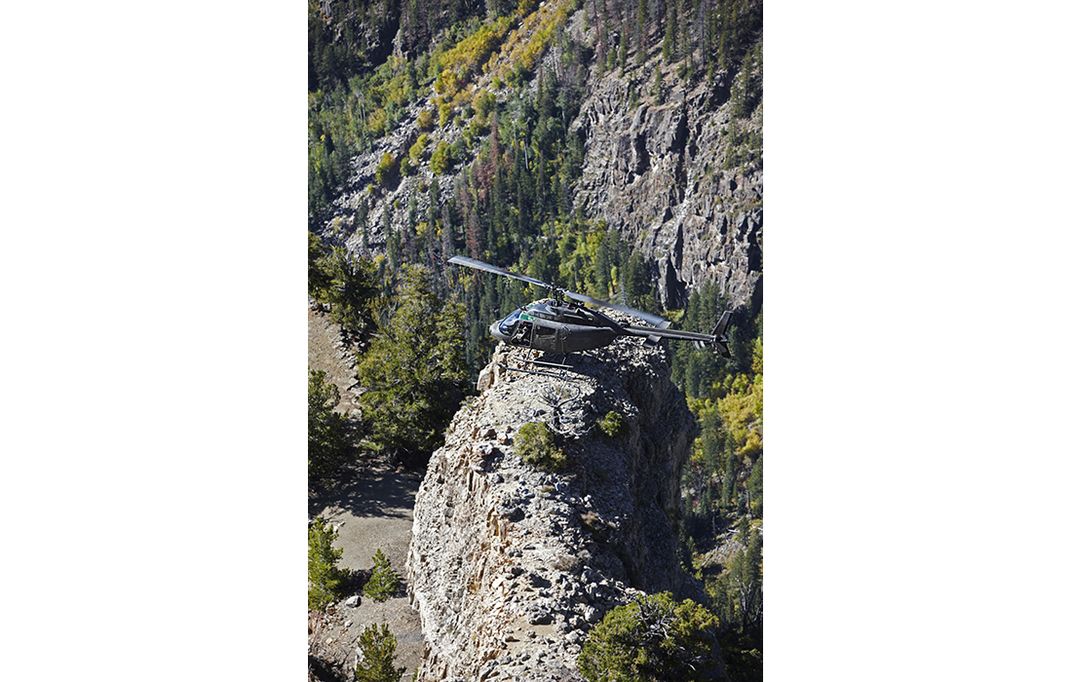

An Army school in Colorado shows military pilots how to master the heights.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/6f/166fefc6-570e-4005-9343-170caafc99b1/helicopter_mountain_flying_billboard.jpg)

Most U.S. military helicopter pilots learn to fly at sea level, where the air is dense enough to provide the greatest lift for the rotor blades and the engines can deliver peak power. But at higher elevations, where the air is thinner, a pilot has far less room for error. Nearly two decades ago, the U.S. Army opened a training center to prepare pilots to fly missions in mountains or hot temperatures (in which the air also is thinner) or with a heavy load of fuel and cargo. At the High Altitude Army National Guard Aviation Training Site or HAATS, 126 miles west of Denver, helicopter pilots learn skills that will help them survive deployments to places like eastern Afghanistan’s rugged Hindu Kush mountain range.

“The overarching goal of HAATS is to dramatically increase the students’ situational awareness while operating in a high, hot, and heavy environment,” says Colorado Army National Guard pilot Darren Freyer, a chief warrant officer and instructor at the Gypsum, Colorado school. “We ask the students to define ‘power management’—most students stumble around defining this term. HAATS defines power management as knowing how much power is required for a particular maneuver [like takeoff, hover, or landing], and constantly being aware of how much power is currently available. If you don’t have enough power available for a maneuver, the helicopter will not perform it. It’ll come back to Earth, piloted by gravity, not you.”

Freyer tells me this as we course up a canyon deep in the Colorado Rockies in an OH-58A Kiowa last fall. A Colorado native, he lives and breathes high altitude. Freyer’s home is near the mountain resort Vail, and his office throughout the year is the right side of a cockpit. Flying at altitudes ranging from 6,500 to more than 14,000 feet, he looks down at snowfields, stands of aspen, and wind-scoured mountain ridges.

At the school, Freyer and other instructors teach pilots how to calculate their power margin—the difference between how much power they need and how much they have, based on the helicopter’s weight, pressure altitude, and outside temperature. At sea level, the power margin might be as much as 35 percent, a substantial cushion. “Up high, especially if the helicopter is loaded down—as combat circumstance often forces crews to do today in Afghanistan—you often have margins of between one and five [percent], sometimes no margin at all,” says Freyer. No margin means that even a slight change in wind direction can flip the power margin into the negative range and cause a helicopter to tumble out of the sky. The instructors also go over such topics as how environmental conditions like wind or blowing snow can affect a helicopter’s ability to hover, how to pick a good landing site on a mountain, and when to either commit to or wave off from a landing.

The school began in 1985, mandated to train Colorado National Guard pilots in mountain flying for local search-and-rescue missions. In 1987, it evolved to train Army National Guard pilots from other states to deploy to the mountainous regions of Honduras, for humanitarian projects like building roads. It became HAATS in 1995. Today it is a training center for helicopter pilots from all branches of the U.S. military, as well as those of allied nations, including Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the Republic of Georgia, and Slovenia. As military pilots deployed to Afghanistan in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the Department of Defense began to focus on the training that HAATS does. Now staffed with 36 personnel, including 11 instructor pilots, HAATS is the only training facility of its kind in the U.S. military.

“We’ve put 420 pilots per year through our training in the last couple years,” says base commander Major Tony Somogyi. “We bring pilots up here from sea level, throw them in an uncomfortable environment, and train them. But we never did anything for the development of crew chiefs; now we’re doing crew chief training too.”

Somogyi, who flew OH-58D Kiowa Warriors with the Army for eight years before transferring to the Colorado Army National Guard, says crew members are vital in keeping landings and takeoffs in mountains safe because they can see things the pilot can’t, like the helicopter’s wheels.

Somogyi brings up a troubling statistic: Of the U.S. Army helicopter crashes from 2002 through 2011, about 20 percent could be attributed to enemy fire. The other 80 percent? Pilot error. “The fact that we’re destroying more aircraft on our own without enemy contact shows that training like this is invaluable,” he says, but he adds that the effectiveness of the training is impossible to quantify: “You can’t put a number on the accidents you’ve prevented.”

Each course at HAATS spans five days: eight hours of classroom time on Monday, three days of flight training, and written and inflight testing on Friday. Among the helicopters the students fly are OH-58s, CH-47 Chinooks, UH-60 Black Hawks, and LUH-72 Lakotas, although they are free to bring their own.

“We run courses 38 weeks per year, breaking for holidays and rifle-hunting season, which is part of our land-use agreement,” Somogyi says, explaining that the school has approximately one million acres, primarily in U.S. Forest Service land, in which to train. While teaching most of the time, HAATS pilots are also on call for search-and-rescue missions year-round. “Last year we set a record at HAATS by flying 28 search-and-rescue missions and saved 14 lives, mostly climbers,” he says.

HAATS instructor CWO-4 Anders Nielsen flew one of the most dramatic rescues in a UH-60 on September 21, 2013, after a civilian pilot “waved off” an attempt to pluck a fallen climber from the shoulder of one of Colorado’s most popular mountains, North Maroon Peak, just outside Aspen. “Aspen Mountain Rescue had the climber stabilized at 13,500 feet,” Nielsen recalls. “It was getting near sunset, so we had to act fast. We didn’t want to be up there flying on night-vision goggles.” Nielsen, who has more than 6,000 hours of helicopter time (mostly in a Black Hawk) over the course of 24 years, determined his power required and power available with his copilot, HAATS instructor Captain Tom Renfroe.

“I had a power margin of two percent,” Nielsen says. “And there were winds coming out of the west at 15 to 20 knots. The victim was located on the east side of the peak, so we’d be in the lee side of the winds, but that could have proven disastrous, as you can never predict swirling eddies, only prepare for them with an escape route.”

Once he sighted a suitable landing zone about 100 yards from the victim, Nielsen did a flyby to decide exactly how he should land. “I flew past and found my decision point, the point at which we teach students to decide whether to proceed with a maneuver or wave off.” To determine that, Nielsen had to study the topography and weather conditions during his flyby at 13,500 feet. The landing zone was tricky: a one-foot by two-foot flat rock on the edge of a cliff. “I was going to execute a one-wheel landing. The wheel is about six feet behind the pilot, so I needed to count on my crew chief, Darryl ‘Frosty’ Foster, to talk me in with inch calls.”

On final approach, Nielsen stopped about 15 feet out. “Renfroe called out my power numbers one last time, and I felt that everything was stable. That’s when I made the decision with my intent to land. Then Frosty calls me in the rest of the way.” With Foster’s help, Nielsen kissed the small rock with the Black Hawk’s right wheel, then started coming off power, to “anchor” the helicopter solidly enough to load the victim.

“The more weight I can put on the rock, the less the turbulent winds around me can toss the helicopter around,” Nielsen says. He came down to 51 percent power, using the helicopter’s cyclic and anti-torque pedals to keep the Black Hawk level. “That’s when Frosty said the rock was shifting, so I pulled it up to 55 percent.” With the help of the air crew, the rescuers quickly loaded the victim onto the Black Hawk, and once everyone was clear, Nielsen banked the helicopter away and flew down into denser, friendlier air. Later, he and his crew flew back to transport the rescue team to lower ground.

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jeffrey Girouard, the chief instructor, recounts an attempted rescue when he flew his helicopter at the absolute limit of its capability for the conditions: “A hiker had fallen 300 feet down a sheer cliff in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of southern Colorado. I can’t believe he hit the ledge—it was only 10 feet wide, if that,” says Giroud. Hovering at an altitude of more than 12,000 feet, aimed into the wind with no power margin at all, “I simply didn’t have enough space to put a skid on the ledge to rescue the hiker.”

As he and a sheriff who was coordinating a ground rescue effort assessed the scene, the wind suddenly shifted, nudging Girouard’s power margin into negative range. “I developed a slow right [clockwise] yaw, and I had full left pedal in,” he says. Lacking the power at that altitude to stay airborne, he used a technique seemingly counterintuitive for keeping a helicopter in the air in such a circumstance: “I pushed down on the collective, which lowered the angle of attack of all the blades of the main rotor system to reduce their drag, allowing the main rotor system to pick up speed. If you are operating with just a one or two percent power margin, you have to make the approach perfect, and slow. You have to take full advantage of the winds, to try to find the updraft points, and you have to have a way out, an escape route.”

Before coming into a hover to get a look at the climber, Girouard had determined not only what would keep him in that position but where he could go should conditions change, and how to regain stability of his helicopter. Since the situation changed for the worse, Girouard was forced to nose the helicopter away from the cliff into lower, denser air. (The ground team made the rescue.) With more than 7,000 flight hours over 26 years, Girouard is one of the world’s most seasoned rotary-wing pilots, and his experience mirrors that of aviators throughout the Army National Guard, where pilots often continue their careers after finishing years of active duty.

Darren Freyer is now serving in Afghanistan as a pilot of a Black Hawk air ambulance helicopter for G Company, 2-135th, a Colorado Army National Guard medevac unit based at Buckley Air Force Base in Aurora. He says that even as U.S. involvement in Afghanistan winds down, HAATS training remains relevant. “Just because we might not be flying in high, hot, and heavy situations next year or the year after that, hypothetically, doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be prepared to fly in these situations,” he says. “You never know where the next conflict will flare up.”

Last spring, Freyer sent me an email from Camp Bastion, a British base in the Helmand province, about a recent medevac he flew with his platoon instructor pilot, CW3 Dustin Wehlmann, a Kansas Army National Guard member and a HAATS graduate. With Wehlmann at the controls of the Black Hawk, Freyer and three medics aboard were worried not only about the condition of a British soldier injured in a roadside bombing a 10-minute flight away. They were also concerned about taking fire from the Taliban and, on landing, their engines being damaged by the talcum-fine brown dust of the Helmand.

After landing safely and retrieving the soldier, Wehlmann told Freyer he was going to use 80 percent throttle on takeoff, even though both knew 65 percent would do it. Freyer was pleased Wehlmann remembered his lessons from HAATS. Freyer wrote: “A novice pilot will paraphrase this to ‘I will use the least amount of power always.’ Graduates of HAATS know a more accurate and precise statement is ‘I will use the appropriate amount of power.’ In our case, 80 percent is the appropriate amount of power, as it will ensure a takeoff which gets us up and out of the extremely hazardous dust cloud our rotor system will generate....Thankfully, we do not need to ‘put the hammer down’ flying home, as [one of the medics] tells us our UK soldier has feeling and movement in all limbs. A wonderfully executed power-managed flight, along with a soldier who is going to be okay, leaves all five crew members with a collective feeling of success.”

He hasn’t yet had the opportunity, but Freyer hopes to visit other units in Afghanistan, dispensing advice and encouragement to fellow pilots flying high, hot, and heavy in some of the world’s most hostile terrain.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ED_DARACK.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/72/b47249e8-86e2-4e77-ab49-eb100f6e1c0f/mountain_helicopter_billboard.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ED_DARACK.jpg)