The Guard at NATO’s Northern Gate

With a new force of F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, Norway readies for Europe’s next threat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/35/ae35789d-774a-44e6-a14e-111a290f48f2/09zc_on2016_orlandlanding2mortenhancheimg_84192014-09-05_live.jpg)

Some nights, sitting at a table in a hotel restaurant 17 stories above the Bodø quay, you may see what looks like a spark rise from the Norwegian coast and fly off into the night. Another follows, then both wink out in the distance. They are F-16s from the Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNoAF) stationed here in Bodø [pronounced “BO-deh”], either on a training flight or scrambled to intercept an aerial visitor, probably a Russian one, skirting Norwegian airspace.

Though the conversation around the restaurant is mostly in Norwegian, you also hear diners chatting in English, a good deal of it concerning aviation. The room is stocked with tech reps tending the flock of F-16s stationed here, and preparing for the Lockheed Martin F-35A Lightning IIs that will soon begin their migration to Norway. The prospect of their arrival has already begun to transform not only this nation’s air force, but every branch of its military.

Bodø marks the end of southern Norway. The railroads stop here, so to push on northward one drives, or takes the inter-island ferries, or flies from an airport shared by the city and the armed forces. The field became briefly famous in 1960 as the intended destination of the Lockheed U-2 flown by Francis Gary Powers, whose flight across the Soviet Union from Pakistan was interrupted by a Soviet surface-to-air missile. Located on a peninsula a healthful walk from the city’s center, the airport is a living record, in which one can trace the evolution of Norwegian military aviation over the last seven-and-a-half decades—since April 9, 1940. That was the Tuesday on which Nazi Germany invaded Norway and began its occupation. The Tuesday when Norway’s military clock was reset forever.

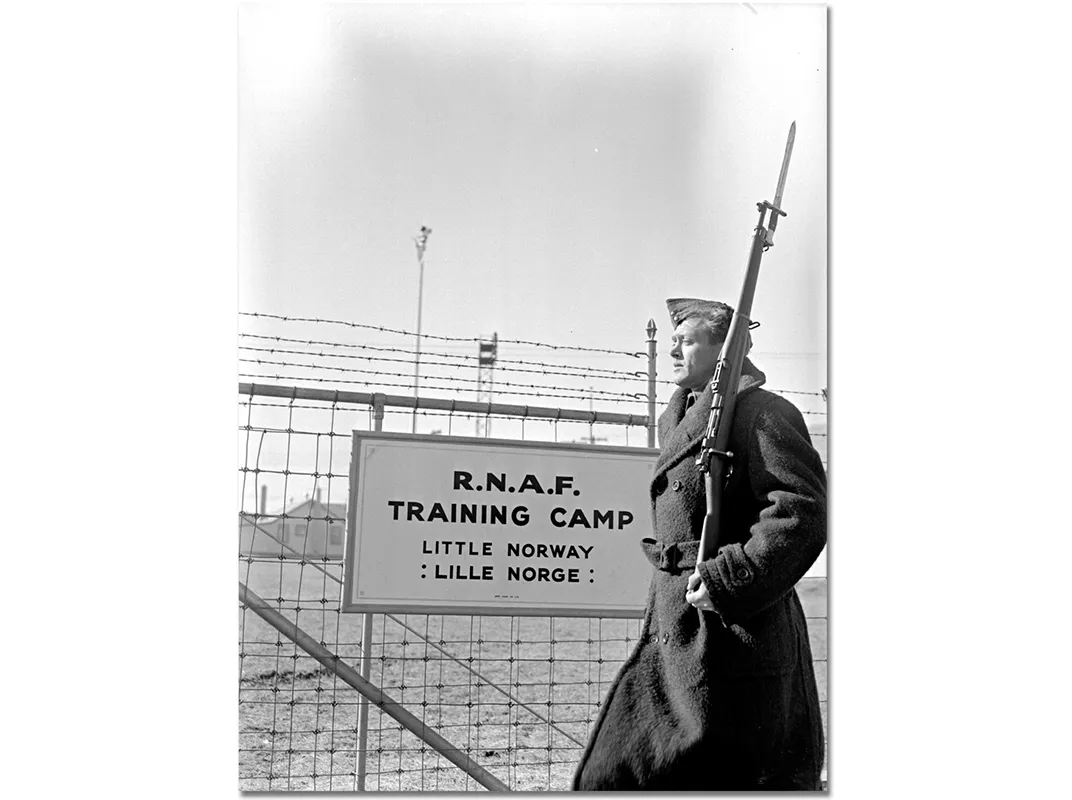

In the early days of World War II, the field was home to Britain’s 263 Squadron and its 16 Gloster Gladiator biplanes, and the 46 Squadron, with eight Hawker Hurricanes. During the occupation, those units retreated to England; then the Norwegian elements moved on to a base near Toronto, which came to be known as Little Norway. The Norwegian pilots returned to England in time to fly Spitfires in the Battle of Britain and on D-Day, and to launch Mosquito sorties against German targets in their occupied homeland. In November 1944 the Royal Norwegian Air Force became a separate armed service, while still an air force in exile.

When Norway’s fighter pilots returned after World War II, most of them were still young despite their combat experience, with long careers still ahead of them. They became the leaders of the newly coined RNoAF, and led it until the 1970s, when Northrop F-5s and Lockheed F-104s (and Canadair CF-104s) were the frontline fighters.

Now, the top officers are all F-16 pilots. Brigadier Lars Christian Aamodt, chief of air operations at RNoAF headquarters in Rygge, southeast of Oslo, and his boss, Major General Per-Egil Rygg, the chief of staff of the Royal Norwegian Air Force, are both F-16 pilots. Both have trained and lived in the United States, and both speak fluent American English. They preside over a force of about 3,000, charged with defending a country with the area of Montana and the population of Colorado: a little over five million.

The RNoAF’s 132 Air Wing operates from a cluster of green-roofed structures south of the runway. Its 331 and 332 Squadrons—they kept their old RAF numbers, and a pedestaled Spitfire replica climbs eternally outside the headquarters building—fly about half of Norway’s 57 F-16s, housed in sod-roofed shelters on the field. (The others are at Ørland, northwest of Trondheim.)

“We did have a mountain facility,” says Colonel Band Reider Solheim, a 49-year-old fighter pilot who commanded the 132 Air Wing and the Bodø base until August 2016. What remains of that cold war relic is on another part of the field, where a low hill was hollowed out to accommodate a squadron’s worth of people and airplanes inside a granite shell. “We abandoned that in the 1990s,” says Solheim. By then the once-inevitable nuclear confrontation between East and West had cooled to improbability, and the cold war entered its decades-long thaw.

Lately, a new chill in the geopolitical air has revived some of those old tensions. Russia has resumed sending the occasional Bear, Blackjack, or Backfire bomber on provocative flights along the coasts of NATO member nations. “About once a week,” Solheim says, “pretty stable since 2010. In the cold war, we did a lot of flying, once or twice a day. A real scramble, we will go up and meet them. Sometimes they just turn around, or they will fly their route all the way down to Portugal. We follow them to Bergen,” in Norway’s south. From there, other NATO shadows take over.

Conducted over international waters, the Russian flights are perfectly legal, although the Russians rarely turn on their transponders for air traffic control. The meetings between interceptor and intercepted have lost much of their former intensity. In fact, Solheim and his pilots welcome the practice. Intercepting aerial visitors from Russia could become a form of recreation, except that the intruders are projecting Russian power, already on display in Ukraine, Syria, and the Baltics. The F-16s Norway sends to meet them fly armed.

In service now for more than 30 years, the Norwegian F-16s have been through their midlife updates, which, among other things, rigged them to carry the AMRAAM, a beyond-visual-range weapon, in addition to Sidewinders and 20mm cannon. The F-16 has become a formidable multi-role platform.

“We have a lot of airspace up here,” Solheim says. “And we train with the Swedes,” with whom Norway has a no-borders agreement. Without a tanker fleet of its own, Norway depends on U.S. aircraft to refuel the fighters. Operating in Norwegian airspace, the Fighting Falcons fly as Norwegian assets. On missions outside Norway’s airspace, the F-16s are NATO’s.

Whether flying intercepts or not, the Norwegian pilots are combat-ready. Last summer Norway sent its first contingent of F-16 pilots to learn the F-35 at Luke Air Force Base, outside Phoenix, Arizona. Lieutenant Colonel Henning Homb, commander of the Bodø base, says Norway will phase in the F-35 and retire its Fighting Falcons in waves, beginning next year. He expects that by 2022 the F-16s will be gone. Until they’re relieved, the F-16 patrols will keep a Quick Reaction Alert on standby.

On an October afternoon in 2015, two quick-reaction F-16s wait like saddled thoroughbreds in shelters near the pilots’ billet, only a short taxi from the midpoint of Bodø’s 9,167-foot runway. From there, they can launch to the east or west, depending on winds.

Their pilots are a lanky, cheerful redhead, call-sign Goofy—names are not given out—and a darker, quieter one, call-sign Chain. Both are in their 30s. Goofy already has his orders to train at Luke in 2016, and Chain is waiting to hear.

Once alerted, “we can [launch in] 15 minutes,” says Goofy, “and sometimes less... an hour to any place in Norway.”

“In most cases quicker,” Chain interjects.

It’s fair to ask how the newer F-35 fares in a scramble. Experts at the Joint Air Power Competence Centre, a NATO “Centre of Excellence” with representatives from 15 member nations, say it’s too soon to tell. The Lightning II has only recently been deemed “Initial Operationally Capable.” But they pointed out that many factors beyond the mechanical abilities of the aircraft play into scramble speed, including the training and experience of the ground crew.

Trained in the U.S.A.

Norway’s World War II experience and its long, deep relationships with the United Kingdom and the United States have helped shape its military doctrines. “A lot comes from the RAF and U.S. Air Force,” Rygg explains. “We’ve always educated our pilots in the U.S.” As Øistein Espenes and Nils E. Naastad, historians at the RNoAF Academy, observed in an article in the Spring 2000 issue of Air Power: “MAP [Military Assistance Plan] Americanized the RNoAF, not only in terms of equipment, but perhaps even more importantly by introducing American methods of management. The RNoAF was restructured and reorganized, and by 1954 rose as an Americanized Phoenix of British origin to be deemed combat ready.”

Through direct purchase or a Military Assistance Plan, the Norwegians have obtained most of their aircraft from America. These have been mostly fighters, intended primarily for air defense. Norway has never had a Strategic Air Command or Bomber Command. All RNoAF chiefs have been fighter pilots.

The air force’s traditional role has been to guard Europe’s vulnerable northern portal, as part of NATO, and to control Norwegian airspace in the event of attack. The air force has given little emphasis to offense. The doctrine reflects the hard lessons of Norway’s 1940 trauma, when a feeble, obsolescent air arm could not provide adequate cover for reinforcements arriving from abroad. Now, in these conversations, one keeps hearing the refrain: It will not happen again.

In April 1949 Norway joined NATO. But, like Switzerland, it stayed out of the European Union, relying instead on bilateral agreements concerning travel and trade.

Through the decades, aircraft by aircraft—F-84 Thunderjets, F-86 Sabres, F-104 Starfighters, F-5 Freedom Fighters—the RNoAF reinforced its emphasis on air defense, dialing back the role of ground attack. What Norway really wanted was a fast-climbing, hard-turning air superiority fighter—a fighter pilot’s fighter—to wage a defensive war that, in Norway at least, would most likely be won in the air, not on the ground. As it happened, they would opt for a design that began as a high-performance fighter but, to the surprise of some, would evolve into an airplane-of-all-work. The General Dynamics YF-16 made its first flight in January 1974. Norway would eventually buy 74 of the production version. Lieutenant Colonel Dag Henriksen, the 44-year-old Ph.D. who directs the Airpower Department at the RNoAF Academy in Trondheim, has written that the key transformational process in the RNoAF was the evolution of the F-16 community. “When I said transformation,” he explains, “I meant the somewhat frictional process of moving from national defense, fighting the Russians in a cold war scenario, to ‘out of area’ operations…after the cold war.”

These “out-of-area operations” began in 1999, when Norway sent six of its F-16s to Operation Allied Force, NATO’s Balkan intervention. Operating out of the Grazzanise air base in Italy, the Norwegian fighters flew combat air patrol missions—“not the war the RNoAF had trained for,” as one pilot recalled. It deployed to the Kosovo conflict equipped for air-to-air combat, which did not materialize. But the deployment marked a turning point. This was the first time Norwegian aircraft had been sent to war since 1945.

In October 2002, Norwegian F-16s, along with F-16s from the Netherlands and Denmark, deployed to Manas air base in Kyrgyzstan as part of NATO’s contribution to Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. And there, one squadron commander reported later, “we entered the close air support role…almost one hundred percent backwards.” Having dropped no bombs from 1945 to 1999, Norwegian fighters dropped no bombs in Kosovo and only seven in Afghanistan.

But by 2011, when Norwegian F-16s deployed to Crete to participate in Operation Odyssey Dawn in Libya, they were truly multi-role fighter-bombers, providing both air defense and close ground support. In Libya, they dropped 588 bombs during six months of conflict. The F-35s Norway is procuring are Joint Strike Fighters, with as much emphasis on the middle word as on the last.

The ties of coalition have been strengthened as Norwegian F-16s have joined the aircraft of other NATO members in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Libya, as well as in a series of Arctic Challenge exercises flown from Bodø, and have participated in Baltic Air Policing to give cover to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, NATO partners since 2004.

Henriksen points out that, taken together, Norway and its allies have a huge number of fighters. “The ministry of defense is more often using the expression ‘a European medium power,’ ” he says, which significantly relates to the purchase of the F-35. “In real money, although the numbers vary, we are just around number 10 in NATO. What I think is more interesting is the mentality. The Royal Norwegian Air Force have grown more accustomed to the use of force. You want to interact, to take part.”

Integration

Lieutenant Colonel Baard Bakke is head of the RNoAF Jet Fighter Project, which has overseen the selection of the Joint Strike Fighter and its complex integration into the Norwegian armed forces. The 46-year-old F-16 pilot has been based at the F-35 Joint Program Office in Arlington, Virginia. The decision to go with the F-35, he says, “was based on capabilities and price…and being in a big partnership.” After looking at performance—at the airplane’s ability to conduct a wide variety of missions in a high-threat environment—the project had no doubt about the selection.

Norway has said it intends to buy 52 F-35As, the type flown by the U.S. Air Force. So far it has purchased 22, with deliveries to begin next year. Bakke believes the country will opt for the full 52.

But what about the chorus deriding the F-35’s cost, delays, software glitches, and poor performance in mock fights with legacy fighters?

“I have been flying the F-35 for quite some years now,” he puts “flying” in air quotes—“in a simulator environment. The F-35 isn’t built for a dogfight. It is very popular to talk about this one-on-one. But [such talk] should die, really. The fight can happen in a decidedly different way than it would in the F-16. One-on-one with guns only doesn’t really matter. You did something dramatically wrong if you ended up in a dogfight” in the F-35.

The Joint Air Power Competence Centre experts maintain that the F-35, like the F-22, has been designed “to engage without being engaged in turn,” and at visual range, that engagement isn’t always a furball. They point out that the F-35 can engage a target that’s behind it, something more traditional fighters can’t do.

No one in Norway seems troubled by the offensive mission the F-35 is designed to fly, or the claim that it will be able to penetrate and survive high-threat environments. “The F-16 has a pretty good offensive capability,” says Aamodt.

By the time all the F-35s are in place, the RNoAF will be a much different armed force. In August 2015, a force reorganization moved most of the 132 Air Wing to Ørland. As the F-16s are phased out, the airport will continue as a civilian hub, but the air station, where so much of Norway’s aeronautical history can be read, will itself become history.

A pair of combat F-35s will stand a Quick Reaction Alert at Eveness, a forward base well to the north. The remaining F-35 fleet will operate from Ørland, which is currently being churned into a major construction site. A large squadron building there will integrate training and simulators. “Everything will happen in one location,” Bakke says. “All the first-level maintenance. We’re building hangars, shelters, a good base to operate from.”

“Ørland,” says Aamodt, “is the future.”

Early Warning

Sørreisa is a tiny Arctic community beside the still waters of the Reisafjorden, in which the surrounding granite mountains and fir and birch forests are perfectly reflected. Seven miles southwest of town, a narrow track splits off the main highway and winds up a mountain called Gumpen—“wolf,” in the language of the indigenous Sami people. About halfway up, a young man in fatigues, cradling an HK 416 assault rifle, guards a gate, beyond which lie a few wooden buildings wearing the green and white livery of the Norwegian military. This is the Sørreisa Control and Reporting Center (CRC) or, rather, its outer shell. The site was designed to be impregnable to any kind of attack: nuclear, biological, chemical, or conventional.

Inside the CRC, the mountain’s rough interior is hidden by walls and ceilings, and one becomes less conscious of being interred under hundreds of feet of rock. Save for the absence of windows, this could be a modern office building. From here, specialists assigned to RNoAF’s 131 Air Wing can watch, listen in on, and talk to everything that flies in and around Norway.

“We are air traffic control for the military,” explains the station’s commanding officer, Colonel Stig Jonny Haugen, a big, amiable man in his 50s. He was born in Sørreisa in 1962, the year the center opened, and came to it in 1981 as a conscript. (Norway asks every qualified young person—women have been included since 2013, although they cannot be made to serve against their will—to spend about a year in military service.) He spent years at various headquarters and control centers in Norway and abroad, and flew as a tactical director aboard NATO E-3A Sentry aircraft sent to help monitor U.S. airspace after the September 11 attacks. By 2013, he was back in Sørreisa as commander of the facility where his military career had begun.

On a wall near one of the blast doors, a framed, faded color photograph shows a Russian Tu-160 Blackjack supersonic bomber accompanied by Norwegian F-16s in May 1999. The scrambled fighters had been vectored to the bomber by Sørreisa, the first time a Russian aircraft of this type had been identified by interceptors. Haugen was the controller behind that rendezvous.

“We control all the radars there are in Norway,” he explains, referring to a string of installations monitoring the country’s airspace and borders. But those radars are quickly becoming obsolete. “We have radars that were developed and delivered in the 1970s. Also some less than 10 years old.” Like so much else in the Norwegian military, replacing them over the next decade is linked to the arrival of the F-35.

Nearby, controllers are assembling the latest air picture, in which the long, dragon-shape of Norway is defined by greenish blips. Well off to the east, an orange blip appears. An intruder? No, says Haugen. It is one of Norway’s P-3 Orions, out on a morning maritime surveillance patrol.

Highway Patrol

During the cold war, everyone watched the traffic on the marine highway linking Russian naval bases on the Kola Peninsula, which juts east from where Russia and Norway meet, and the Atlantic Ocean. Today, Norway is the only NATO nation still flying maritime surveillance patrols over this vast, busy patch of ice and ocean. It’s an important mission, especially, as one Air Force historian puts it, “when you have the biggest Russian naval base just around the corner.”

Norway’s six P-3s are part of the 333 Squadron of 133 Air Wing, which occupies part of the municipal airport at Andenes, a small community at the north tip of Andøya Island. The air station was sited here for easy access to the heavily trafficked open water linking the Arctic Ocean and Barents Sea to the Atlantic.

Colonel Ingvild Jensrud commands the Andøya base. A former navigator, she was trained for anti-submarine warfare by the U.S. Navy, and helped guide the development of the NH-90 helicopter, a project shared by a consortium of NATO members. Now she leads a unit whose main task is to provide a Norwegian military presence in Norway’s huge share of the Arctic turf.

The Andøya P-3s fly daily patrols that go as far west as Jan Mayen, a Norwegian island northeast of Iceland, and as far east as Norway’s 110-mile border with Russia—and sometimes a bit more. “We are in international airspace for the entire Barents Sea,” says Jensrud. The flights stay at altitude, she says, to get a broad picture of surface activity, then drop down for a closer look. “We rarely go to 250 feet.”

Although the P-3s fly as Norwegian aircraft, the information they gather is relayed back to headquarters and NATO.

While these are mainly military patrols, they also provide surveillance of Norway’s fisheries, and the frail Arctic environment. Between them, Norway and Russia have about half the planet’s Arctic coastline, and claim rights to the abundant resources believed to lie beneath the thawing polar ice. The Orions will provide early warnings of environmental degradation and any poaching of natural resources.

Out on the tarmac, one of the Orions, painted battleship gray, waits to be launched on another day’s patrol. Two others are inside an enormous hangar, where ground crews swarm over them. On their vertical stabilizers is the haloed stick figure made famous by the 1960s television series The Saint, with Roger Moore as the Simon Templar character from Leslie Charteris’ novels.

“We are proud of the saint figure,” says Torbjorn Haugen, a retired RNoAF major who has spent about 14,000 hours flying as navigator on Andøya aircraft. “In the rebuilding of the Norwegian air force after World War II,” he says, “air squadrons were assigned call signs.” The Andøya unit was given Saint.

“We are very fond of the P-3,” says Jensrud, “and would be quite happy operating it for a number of years, if we can find spare parts.” But she knows the Orions are reaching an age where they will have to make way for a younger generation of aircraft.

Over the next several years, the much-anticipated covey of F-35As will arrive, bringing new capabilities that will dominate Norwegian military strategy for decades to come. The F-35 will become Norway’s main line of defense, and if called out, demonstrate its strike capability.

The beautiful F-16, the indestructible Orion, the radars controlled by Sørreisa—all of those shining new things bought 30 or 40 years ago have grown old. Now, although the Russian bear seems to be coming out of hibernation, the threat of a broad war has diminished, while the prospect of “out of area” operations has grown. How lucky we are, that we cannot see the future.