That’s All, Brother

A last-minute reprieve for a D-Day veteran.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/23/2f23dfb6-33be-4487-8f17-4a05de475a8a/21c_grtflights2017_c47jimkoepnick_live.jpg)

The first Douglas C-47 Skytrain to lumber into the dark on June 6, 1944, launched perhaps the single greatest save in history: Operation Overlord, the invasion of Europe to save it from Nazi domination. This particular Gooney Bird had a message on its nose for Hitler, painted by its captain, Colonel John Donalson: “That’s All, Brother.” But long after the D-Day invasion of Normandy was etched into history, the airplane that led the charge got lost. Skip forward more than 60 years to Montgomery, Alabama, where a pair of curious and persistent historians stumbled upon the clues that led to the airplane itself being saved.

“I was never looking for it,” says Matt Scales, who is an Alabama police officer and also in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. “And it wasn’t just me either. Ken Tilley [now Fort Rucker’s Army aviation historian] was sitting right beside me when we found it.” What they found at first wasn’t an airplane, but Colonel Donalson.

In 2007, Scales was a KC-135 boom operator in the Alabama Air National Guard’s 106th Refueling Squadron, temporarily assigned to the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base. A trained historian, Scales was curious about his squadron’s history and decided to investigate the rumor that one of its members, Colonel John Donalson, had flown the lead C-47 on D-Day (after small “Pathfinder” teams first marked the drop zone for the main invading force). It made no sense to Scales, who knew that the 106th served in the Pacific flying B-25s. But maybe Donalson, who was in the 106th before and after the war, had served with a different unit during the war.

Scales and Tilley looked into the records of the 438th Troop Carrier Group, the unit of C-47s that took the lead on D-Day. “Ken pulled out their history, and boom—the very first page had a huge picture of John Donalson,” he recalls. Donalson had transferred (for reasons Scales still doesn’t know). But then they found something extraordinary. “The history said Colonel John Donalson and Lieutenant Colonel David Daniel took off for the invasion in C-47 serial number 42-92847,” says a still-amazed Scales. “This absolutely floored both of us. You rarely see serial numbers in these histories. I said to Ken, ‘There may be a chance this airplane is still around!’ ”

They looked it up. The airplane survived the war, was sold as surplus, and wound up in Mesa, Arizona, restored by its owner with Vietnam-era markings. Scales and Tilley were thrilled—but they were sure the airplane they’d found was named Belle of Birmingham. Since Donalson and Daniel were from Birmingham, and the aircraft that Donalson ordinarily flew was the Belle, they assumed that that was the aircraft the two had flown on D-Day. They shared the news with the current owner and left it at that, happy that the airplane was safe.

Scales moved on with other research, but couldn’t quite get the airplane out of his mind—and it still had a few secrets to reveal.

Three years later, another clue appeared. Online, Scales found a film shot on June 5, 1944, that showed a C-47 being loaded for the invasion. Suddenly he saw something amazing: The tail number clearly was visible—and it matched the one they’d found at Maxwell and traced to Mesa! But the name painted on the nose was not Belle but rather That’s All, Brother. Pictures don’t lie: Donalson and Daniel clearly did not fly their customary C-47 on D-Day. Scales soon learned why.

As pilots of the lead aircraft, Donalson and Daniel were required to have radar equipment on board. Belle didn’t have it; That’s All, Brother did.

Then Scales learned that the airplane was in danger of being altered forever. When he had spoken with the owner three years earlier, the man had mentioned that he might sell it. Scales found out it had been sold to Basler Turboprop Conversions at Wittman Regional Airport in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. “That sent a chill down my spine,” he recalls, “because I knew what would happen to it.” It would have been transformed into a BT-67 turboprop and put to work. “There’s so many C-47s out there. Why convert this one?” he says. He called Basler and told them what he’d learned; the company would soon become instrumental in saving the aircraft.

Late in 2014, Scales chanced upon an article on the Wittman airport website reporting that Basler was thinking of selling That’s All, Brother—still unconverted. Immediately, Scales went on the hunt for a buyer. He contacted dozens of museums and organizations, as well as individuals, but struck out. Six months later, he got a call from Adam Smith, an executive vice president of the Commemorative Air Force, an organization dedicated to preserving combat aircraft. The group had decided to launch a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money to purchase That’s All, Brother from Basler. The campaign far exceeded its goals, and the aircraft is now well on its way to being returned to its airworthy D-Day configuration.

Meanwhile, Scales has learned more about the men That’s All, Brother carried on D-Day. It left Greenham Common just before midnight on June 5 with seven crew members (Scales has tracked down four of their families) and paratroopers from the Infantry Regiment Headquarters of the 502nd. Unlike many that followed, the troops dropped onto their target, northeast of the French village of Carantan. Being the lead ship, the airplane didn’t meet the resistance that, along with weather and poor navigation, caused some later C-47s to miss their drop zones. “The navigator said, ‘We escaped most of the flak because the Krauts were still sleeping when we came over,’ ” Scales says.

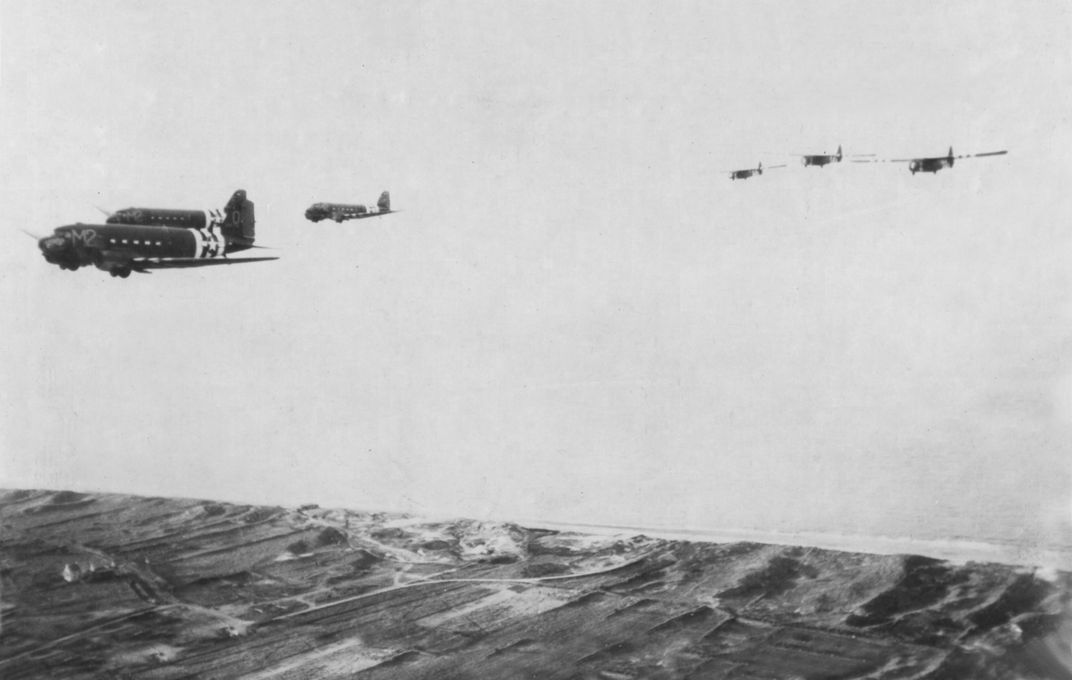

The scale of the aerial armada that followed was vast. In the first wave alone—code-name Albany—432 C-47s carried more than 4,000 paratroopers to France. They came in low to evade radar and kept radio silence. Sixty percent had no navigators. They flew through fog, low clouds, and flak. Drop zones were missed, chutes opened too low, and Germans were waiting. But wave after wave came—more than 13,000 paratroopers crossed the channel that night; the next day, almost 4,000 troops flew into France in gliders towed by C-47s.

Donalson and Daniel returned to the Belle for the rest of the war. That’s All, Brother went to another crew, resupplying troops at Bastogne and in the Battle of the Bulge, Operation Market Garden, and Operation Varsity, the final paratrooper drop across the Rhine into Germany. Ira Bailie, 94, of Turlock, California, was a member of that crew. Says Scales: “He’s the only living connection to the aircraft.”

That’s All, Brother will join 20 airplanes flying from the United States to England to re-enact the historic D-Day mission.