What Couldn’t the F-4 Phantom Do?

A tribute to McDonnell’s masterpiece fighter jet.

:focal(555x361:556x362)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/eb/f8eb53a8-dbc0-4614-aad6-eac33ae466b3/f4_bombs.jpg)

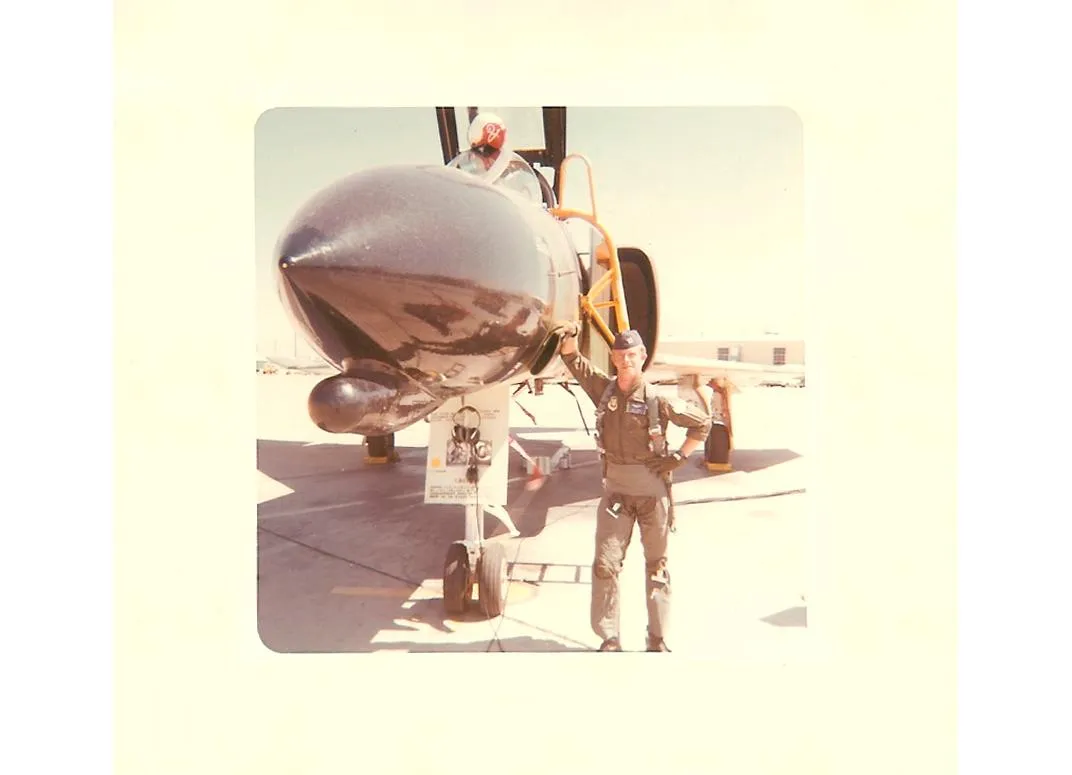

First, they tried an F-104. “Not enough wing or thrust,” recalls Jack Petry, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel. When NASA engineers were launching rockets at Florida’s Cape Canaveral in the 1960s, they needed pilots to fly close enough to film the missiles as they accelerated through Mach 1 at 35,000 feet. Petry was one of the chosen. And the preferred chase airplane was the McDonnell F-4 Phantom.

“Those two J79 engines made all the difference,” says Petry. After a Mach 1.2 dive synched to the launch countdown, he “walked the [rocket’s] contrail” up to the intercept, tweaking closing speed and updating mission control while camera pods mounted under each wing shot film at 900 frames per second. Matching velocity with a Titan rocket for 90 extreme seconds, the Phantom powered through the missile’s thundering wash, then broke away as the rocket surged toward space. Of pacing a Titan II in a two-seat fighter, Petry says: “Absolutely beautiful. To see that massive thing in flight and be right there in the air with it—you can imagine the exhilaration.”

***

For nearly four decades of service in the U.S. military, the Phantom performed every combat task thrown at it—almost every mission ever defined.

“All we had to work with at the beginning was a gleam in the customer’s eye,” said James S. McDonnell of the Phantom’s inception. In 1954, the ambitious founder of McDonnell Aircraft personally delivered to the Pentagon preliminary sketches based on the U.S. Navy’s request for a twin-engine air superiority fighter. The Navy green-lighted McDonnell’s concept, as well as a competing offer from Chance-Vought that updated the F8U Crusader.

In an area of McDonnell’s St. Louis, Missouri factory known as the advanced design cage—a cluster of three desks and a few drafting boards partitioned off with drywall topped with chicken wire—just four engineers worked on the airplane that would propel naval aviation into the future. As the engineers worked, the Navy clarified its concept of air superiority: The service wanted a two-seat, high-altitude interceptor to neutralize the threat Soviet bombers posed to America’s new fleet of Forrestal-class super-carriers. Now designated F4H-1, the project soon engulfed the entire resources of “McAir,” as the company was known. By 1962, F-4 program manager David Lewis would be company president.

McDonnell’s and the Navy’s design philosophy assumed the next war, not the last. The F-4’s rear cockpit was there for a backseater to handle what was sure to be a heavy information load. For the air-to-air encounters of tomorrow, gunnery was supplanted by radar-guided missiles. Though not strictly solid state, the airframe was stuffed with state of the art: Westinghouse radar, Raytheon missile fire control, advanced navigation systems, and an analog air-data computer. A network of onboard sensors extended nose to tail.

On the factory floor, integrating 30,000 electronic parts and 14 miles of wiring gave troubleshooters a fit—and job security. Cheek-by-jowl components generated clashing sources of electromagnetic energy. Voltage wandered wire to wire, producing crazy glitches: Gauges displayed 800 gallons when the fuel tanks were empty. Just how convoluted the glitches could get was demonstrated when baffling control losses were traced to a random match between the pitch of one test pilot’s voice in the headset mic and the particular resonance of a signal controlling autopilot activation.

After the F-4 eliminated the F8U-3 in a competitive fly-off, George Spangenberg, an official in the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, declared: “The single-seat fighter era is dead.” Though its General Electric J79 engines advertised its arrival with a smoke trail visible 25 miles away—a Phantom calling card that would take two decades to engineer out—the first F-4 production models rolled off McDonnell’s assembly line with Mach 2 capability as standard equipment and a 1,000-hour warranty. Delivered to California’s Naval Air Station Miramar in December 1960 as a fleet defender purpose-built to intercept high-flying nuclear foes, the massively powered, technology-chocked F-4 seemed to herald the same break from 1950s orthodoxy as John F. Kennedy’s torch-has-been-passed inauguration speech, then only weeks away.

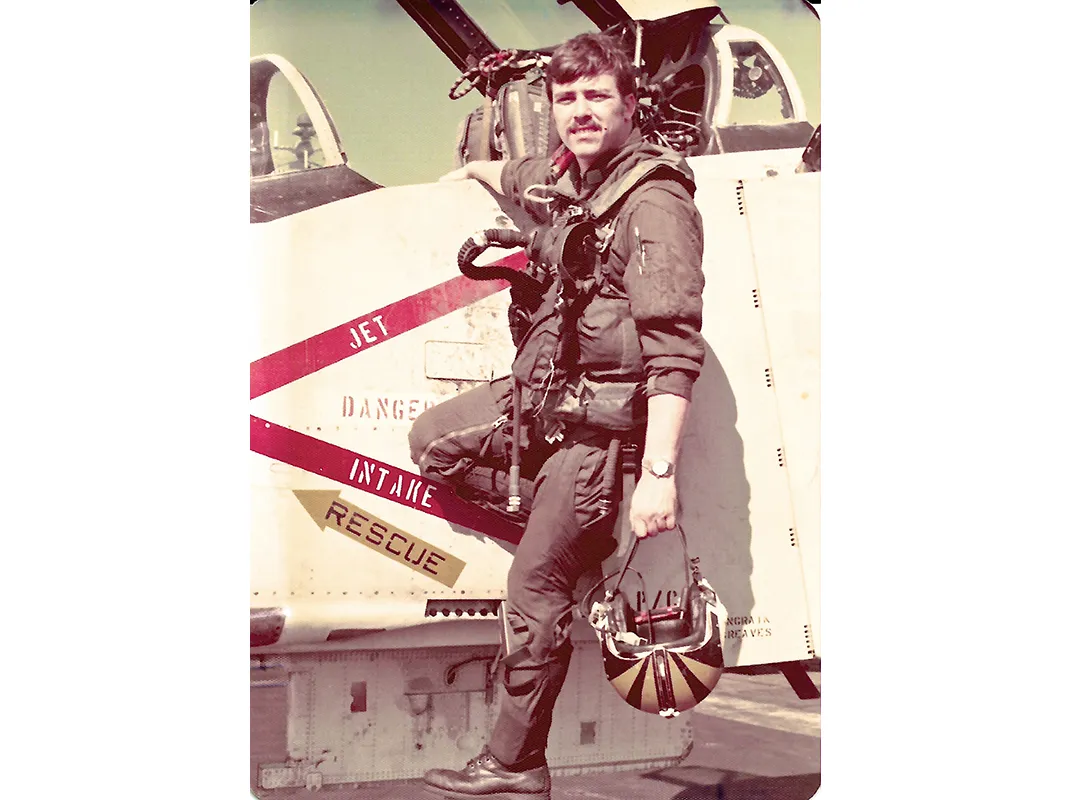

Navy aviators of the early 1950s made do with jet aircraft hamstrung by the requirements for carrier landings. “I wouldn’t say I really aspired to fly the [McDonnell] F3H Demon,” says Guy Freeborn, a retired Navy commander, of the clunky subsonic he once had to eject from. “But then, one day, here was this beautiful new F-4 sitting right next to it.” Suddenly, carrier-based fliers like Freeborn—who would spend two Vietnam combat tours in the front seat of a Phantom—found themselves sole proprietors of the hottest fighter on Earth.

The new jet took some getting used to. Getting F-4s to fly and fight required a team effort: a pilot up front and a radar intercept officer (RIO) behind. The ethos of the solitary hunter-killer, not to mention the ability to single-handedly grease precarious landings on pitching carrier decks, fostered a strong DIY culture among Navy fighter pilots. How to process the notion of a RIO (aka “guy in back,” aka “voice in the luggage compartment”), who wasn’t even a pilot, looking over your shoulder?

Aerial combat in Vietnam had a clarifying effect on pilots’ attitudes toward RIOs. “I loved it,” says John Chesire, who flew 197 combat missions in the Phantom during two tours in Vietnam. “We split our duties, and he kept me out of trouble. Going into combat, the workload was so high that I really relied on the guy behind me.”

Flying into combat without a shooting iron was another matter. “That was the biggest mistake on the F-4,” says Chesire. “Bullets are cheap and tend to go where you aim them. I needed a gun, and I really wished I had one.”

“Everyone in RF-4s wished they had a gun on the aircraft,” says Jack Dailey, a retired U.S. Marine Corps general and director of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

McDonnell’s earliest concept included interchangeable nose sections to readily convert a standard F-4 into the RF-4B, a camera-equipped reconnaissance aircraft. The aircraft’s most photo-friendly asset, however, was speed. RF-4Bs flew alone and unarmed deep into unfriendly airspace. “Speed is life,” Phantom pilots liked to say.

In the front seat of a Marine Corps photo-recon Phantom on more than 250 missions, Dailey was tasked to support Marines on the ground with film and infrared imagery. “We were trying to track movement of the Viet Cong coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” he says. “They moved their trucks a lot at night. We could fly along a road and pop flash cartridges and catch them out in the open.”

The recce pilots in RF-4s had good reason to wish for a gun: The focal length of the RF-4’s camera lens and the required photo coverage imposed a flight regime that didn’t include evasive action. “For photographic purposes, they wanted you flying straight and level at about 5,000 feet,” says Dailey. The predictable flight path and the absence of defensive weapons drew enemy calibers from anti-aircraft artillery down to small arms. “We got hosed down every day,” says Dailey. Often, ground forces simply used barrage fire—large groups firing rifles and other sidearms into the sky simultaneously. Dailey’s Phantom was nailed on nine occasions. A rifle round once penetrated the cockpit, narrowly missing him. Another time he landed with so much engine damage “you could see light shining through.”

Naval aviators were rudely initiated into an F-4 idiosyncrasy: As airplane and deck parted company, the Phantom’s nose initially rose slowly. And with a bit of speed, the nose could over-rotate to a near-stall attitude if not controlled. “It got pretty wild,” says Chesire. “It was always lots of fun to watch new guys take off.”

The snappy response of the J79 turbojets made one aspect of landing on a carrier safer. Earlier engines had often lagged behind urgent power requests. In a memorable moment landing on the USS Midway, Chesire realized that his tailhook had failed to engage an arresting cable—after he’d already fully idled back both engines (a rookie mistake). The Midway’s deck camera recorded his Phantom plunging off the end of the carrier. He slammed the throttles forward. Instead of a large splash, the F-4 reappeared—“going straight up, in full afterburner,” says Chesire—as the J79s delivered just-in-time thrust.

***

Combat air patrol missions were proactive: Instead of escorting or defending, F-4s went looking for trouble. MiG pilots with North Vietnam’s air force were happy to oblige. Part of a two-Phantom patrol to waylay Hanoi-based MiGs, Guy Freeborn launched from the USS Constellation on August 10, 1967. “We were hungry,” says Freeborn, who had never encountered a MiG. Lurking beneath a thin cloud layer, “we figured we might be pretty close to their path. Then, holy crap, here come three MiG-21s out of the clouds right over us.”

The Phantoms shifted into afterburner and sped to 575 mph to develop enough energy to turn aggressively. F-4s hemorrhaged speed while turning—“It was a big, dirty airplane in terms of drag,” says Freeborn—so MiGs could generally out-turn the Phantoms. But the Russian fighter’s fancy footwork didn’t often trump the F-4’s brute, drag-strip acceleration.

The lead Phantom launched two Sparrow missiles, which lost radar lock on the MiGs. Freeborn had other issues beside the finicky, radar-guided Sparrow: Behind him sat a RIO with no combat experience. “I felt I couldn’t rely on him to stay cool, get a radar lock-up, and do what he had to do,” he recounts. As the Phantoms rapidly closed the gap, he chose “Heat” on his front-seat weapons selector and launched an AIM-9 Sidewinder. The streaking heat-seeker locked on to and hit one of the MiGs. Though smoking and trailing fuel, the fighter remained airborne. Before Freeborn could unleash the coup de grâce, the pilot in the lead F-4 finished off the MiG with a Sidewinder. “I told my backseater, ‘Look! That bastard just shot my MiG!’ ”

With only one target remaining, Freeborn quickly triggered another Sidewinder, which promptly misfired. “I said, ‘Oh man, it’s just not my day.’ ” He cycled the weapon selector once more and lit the next AIM-9. “That one blew him to pieces,” he says. He later discovered that neither MiG pilot had survived.

The third MiG-21? Last seen miles away, “streaking back towards Hanoi,” says Freeborn.

***

Before stealth, there was night. Darkness provided cover for the “Night Owls” of the Air Force 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron, based at Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand, during the Vietnam War. “The first time I walked into the squadron, I noticed everything was painted black,” says Doug Joyce, today a retired Air Force colonel.

Missions centered on tactical interdiction and forward air control. Standard strikes were two-craft affairs. “We seldom flew in big gaggles like the day guys did,” Joyce explains. “Nor could we do a lot of jinking around as we came down the chute on a bomb run, because of the risk of spatial disorientation in the dark.” From Phantoms with painted-black bellies, Night Owls dispensed both dumb bombs and laser-guided ones, as well as cluster bombs. Looming terrain and ground fire posed dangers: “37mm anti-aircraft was the biggest threat,” says Joyce. “When they couldn’t see you, they’d just shoot everywhere. If there was any moonlight at all, of course, that F-4 would show up as a big black shape in the moonshine.”

One of the premier graveyard-shift gigs—reserved for the most experienced Owls—was supporting B-52s on bombing raids to Hanoi. “It was pretty breathtaking,” says Joyce, describing pyrotechnics in the night skies in the spring of 1972. “At the very beginning, even with Wild Weasel support, they shot hundreds of SAMs [surface-to-air missiles] at us. At the altitudes the B-52s were at, we were close to the service ceiling of the F-4. You didn’t want to use afterburner because you just lit yourself up. And you couldn’t maneuver laterally in these formations because there were other airplanes next to you.”

Plumes of metallic strips called chaff were released to distract radar-guided SAMs fired at the B-52s. However, Joyce says it had the opposite effect on the F-4s dispersing it: “Here we are in this very heavily defended SAM environment, and we’re appearing on enemy radar screens at the pointy end of a bright stream of chaff.” It amounted to an arrow pointing out the Phantom to North Vietnamese missile operators (see “The Missile Men of North Vietnam,” Dec. 2014/Jan. 2015).

***

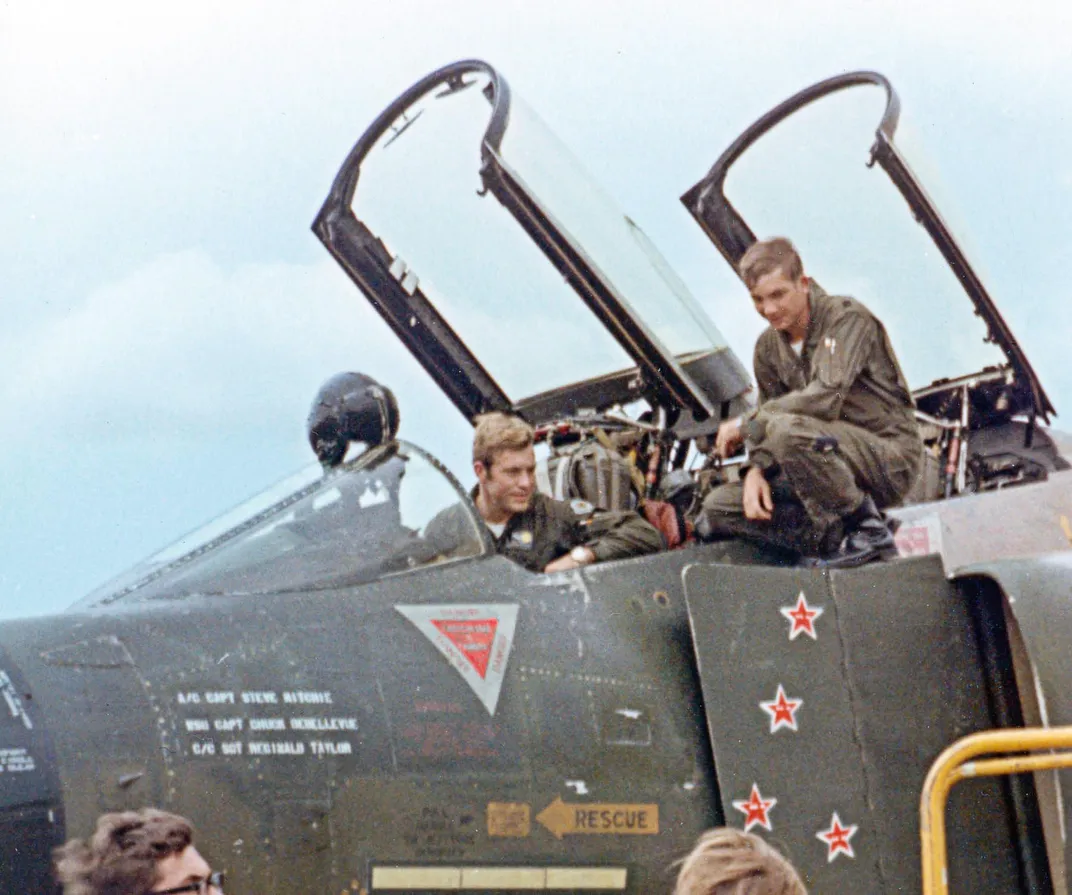

“I always said if you were worried about dying, you weren’t doing a good job,” says Chuck DeBellevue, a retired Air Force colonel. He wasn’t much of a worrier. In Vietnam, DeBellevue flew 220 missions in the F-4 and shot down six MiGs, becoming America’s highest scoring ace of the war.

In 1963, a land-based variant of the Phantom emerged from the McDonnell assembly line. Optimized for both ground support and air superiority, the Air Force F-4C was distinguished by flight controls in both front and back seats and was primed for manual “down the chute” dive-bombing and tactical interdiction. In time, the Air Force bought twice as many F-4s as the Navy.

A pilot surplus put DeBellevue into the F-4 back seat for duty as a weapons systems officer. Unlike their Navy counterpart, the initial backseaters in Air Force F-4s were pilots. However, the Air Force soon decided that navigators were better suited to be F-4 WSOs—or “Wizzos.” “A lot of pilots were not really happy going into the back seat,” says DeBellevue. “But, as a navigator, I was just pleased as pink.” In November 1971, he was assigned to the 555th Tactical Squadron at Udorn, Thailand.

DeBellevue recalls that on the day he reported, he got a blunt greeting from the 555th scheduler. “He looked at me and said, ‘You’ve got one year—if you live. Tomorrow morning you start on the dawn patrol.’ ” As a weapons systems officer, DeBellevue flew nearly 100 missions deep into North Vietnam.

“Crossing the fence into North Vietnamese airspace, you’d start psyching up,” says DeBellevue. Once the F-4 engaged an enemy, he says, “nothing that was happening outside the cockpit was important to me.” With an impending life-or-death event looming at near supersonic speeds, he narrowed his focus to managing weapons systems, acquiring the enemy aircraft on radar, calculating direction of intercept, and feeding the frontseater what he needed to know.

On September 9, 1972, DeBellevue was paired with pilot John Madden on a patrol mission to North Vietnam. Afterward, he was to make one of the last flights leaving Hanoi. “We crossed the Red River and I picked up two blips on the radar at 11 o’clock,” he recalls. Immediately he knew what they meant: “MiG-19s, a very dangerous airplane,” he says. “We couldn’t outrun—we didn’t have gas to run. So we had to fight. We turned on them.” Both MiGs jettisoned fuel tanks, ready to rumble. “They turned into us, and the fight was on,” he says.

“We fired two Sidewinders at the trailing MiG,” he says. “One hit him, and he dropped out of the fight.” DeBellevue couldn’t see that the enemy had in fact crashed and burned, officially making him an ace. “But the other guy was turning hard into us anyway, so we put all our attention on him,” he says. The F-4 launched a heat-seeker, which immediately soared out of sight. “It looked like it was heading for the sun, which isn’t good news,” he says. “Even from the back seat, I could see the MiG, and by this time he was really making angles on us.”

A streak entered his field of view: The errant Sidewinder had rejoined the battle. It ended up in the MiG’s afterburner. “He rolled out wings-level, and then rolled inverted” says DeBellevue, of the MiG’s pilot. “He was at about twelve or fifteen hundred feet when he started a split-S. The first 90 degrees was perfect. After that—he turned to dust.”

Even as he was being toasted at the officers’ club the night of his fifth and sixth victories, “they handed me transfer papers and told me to be ready to leave at six the next morning,” he says. The Air Force removed aces from combat. Stateside, after graduating from pilot training, he was soon in the Phantom again—this time the front seat. When he retired from the Air Force 26 years later, Chuck DeBellevue was the last American ace on active duty.

***

Jim Schreiner had flown Air Force A-10s and was facing a desk job in 1990 when he was offered one more flying tour. He suggested a General Dynamics F-16 or a McDonnell Douglas F-15, the elite fighters at the time. In his book Magnum! The Wild Weasels in Desert Storm, coauthored with Brick Eisel, he described his assignment flying 1969-vintage F-4Gs instead. “It was still a fighter,” he says today, “but not exactly what I was thinking of.”

Twenty years after SAMs downed more than 200 American warplanes in Vietnam, “Wild Weasel” pilots like Schreiner flew upgraded Phantoms into SAM-filled skies during Operation Desert Storm in January 1991. This time, the outcome was very different: Not a single U.S. aircraft was downed by an Iraqi radar-guided SAM.

The Wild Weasel F-4s were fitted with an AN/APR-47 radar-homing-and-warning system, which enabled them to sniff out missile sites. Also, the back-seat configuration was altered to accommodate additional radarscopes and inertial navigation equipment. The Weasel’s most pertinent weapons were two or four AGM-88 high-speed anti-radiation missiles, designed to follow the SAM radar beam right back to its origin.

At 2 a.m. on the first night of the war, Schreiner and his backseater, Dan Sharp, one half of a two-aircraft mission, quickly found the Iraqi SAM sites. Early on, North Vietnamese SAM operators had connected the dots (energized radar equals missile exploding through the roof) and learned to keep their radar powered down until the last moment before launch. “The Iraqis hadn’t yet figured out that it wasn’t a good idea to have the sites up,” says Schreiner. “So they had them all turned on.” The result was a “target-rich environment,” says Schreiner. “Lots of things to look at and shoot at.”

In the cockpit, he watched as each anti-radiation missile found its mark, and the icon representing a SAM site on the Phantom’s radar screen was replaced by a symbol indicating where it used to be. Air-to-air threats were a non-issue—AIM-7 Sparrows carried for self-defense were never used. “There was never any reason to,” says Schreiner. “Had there been any threat, we had plenty of F-15s in the air to take those out.” None of the Wild Weasels were hit by anything larger than small-caliber ground fire. “We continued to fly until they called a halt to the air war,” says Schreiner.

***

“yes, 68,000 is well above the F-4’s operating range,” says Jack Petry. “We weren’t supposed to go above 50-, so we didn’t tell anybody.” That day in January 1965, while he and his backseater, Captain Ray Seal, were chasing the Titan II rocket, their Phantom’s “smash”—flight energy—pushed the space program’s comfort zone.

In his helmet headset, Petry could hear that the range controller at Cape Canaveral was getting nervous: “Break it off,” the controller repeated.

“Negative,” Petry replied, assuring the controller that his finite momentum wouldn’t mess with the missile. “The whole idea was to keep the airplane pointed at the missile,” he says. “So we stayed with it just as long as we had the airspeed—to keep the cameras rolling.”

For a fleeting moment, his altimeter eclipsed 68,000 feet. “We had virtually no energy left,” says Petry. “We weren’t flying anymore at that point—just riding. But the F-4 stayed quite stable.”

The Titan leaned into its trajectory and barreled downrange. Petry broke away inverted and maneuvered to restore airflow over the wings. He and his backseater kept Gemini II in the F-4’s camera sights, he says, “until we fell out of the sky.”