What the Movies Taught Us About World War II

The biggest war in human history inspired hundreds of movies. One of them had to be the best.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/f7/81f75cee-5230-4dc6-ac30-06a8046ac893/08i_am2015_30secondsovertokyocrewspencerbti_live-cr.jpg)

What’s the best film ever made about aviation in World War II? That depends on your definition of “best.” If the best is the one that features the most lovingly photographed parade of period aircraft and the most thrillingly re-created dogfights, your answer might be 1969’s Battle of Britain. Producer Harry Saltzman and director Guy Hamilton had scored a huge worldwide hit with Goldfinger in 1964, and would collaborate on three more James Bond adventures, but their excessively cheerful, star-studded tribute to English courage was badly out of step with the “Make Love Not War” ethos of the era, and it lost a fortune.

(It isn’t Battle of Britain.)

If the best film is the one that best illustrates the stress, exhaustion, and danger to which bomber crews were subjected, particularly in the early years of the war when there were no fighters with adequate range to escort them to heavily defended targets, your choice is likely Henry King’s Twelve O’Clock High, from 1949—one of the many fictional films to incorporate documentary footage of aerial combat. Eighth Air Force veterans Sy Bartett and Beirne Lay Jr. based the screenplay on their novel. Lay had commanded a bomb group and flown a B-24 that was shot down over France in May 1944; resistance operatives helped him hide until he could be reunited with Allied forces after D-Day.

But Twelve O’Clock High tells a larger, more representative story of a nation rising to face an existential challenge. The film is remembered for Gregory Peck’s performance as U.S. Army Air Forces General Frank Savage, who whips the overtaxed and underperforming 918th Bomb Group into shape with a tough-love approach that values achievement above compassion. “Fear is normal, but stop worrying about it,” he tells his men. “Consider yourselves already dead.”

(A great movie—but it’s not Twelve O’Clock High.)

If you confine your survey to films made during the war—which still leaves many hundreds of titles on the ballot—you might pick 30 Seconds Over Tokyo. Mervyn LeRoy’s account of Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle’s April 1942 strike on Tokyo in retaliation for the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor debuted only two and a half years after the event it depicts. Based on the memoir of Captain Ted W. Lawson (played by Van Johnson), who flew a B-25 in the raid, and starring Spencer Tracy as Doolittle, the film was lauded at the time for its authenticity, despite its obvious function as propaganda.

It doesn’t gloss over the brutal reality that after Lawson crash-landed on the eastern coast of China, his leg had to be amputated, or that the raid cost seven airmen their lives, or that all but one of the group’s 16 B-25s were lost. Though the U.S. Navy couldn’t spare an aircraft carrier to stand in for the USS Hornet—the ship that launched the Doolittle raid—the production’s use of real B-25 Mitchells (C and D variants, but nearly identical to the B-25Bs flown in the raid) and canny blending of staged and documentary footage gave viewers a visceral sense of the action.

(You can make a strong case for it, but it’s not 30 Seconds Over Tokyo.)

***

The largest war in history was also, unsurprisingly, the most filmed and most dramatized. In the 1930s, while the rest of the economy was in ruins, the movie business was flourishing, and Washington regarded it with increasing wariness—this industry full of suspected Communists and moral degenerates. But with the meat grinder of World War I still fresh in the public memory, people like Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall knew that convincing America that this war was necessary and winnable would require the help of Hollywood. “After Pearl Harbor, Hollywood signed on to the war effort completely,” says longtime film critic David Luhrssen.

Historian Mark Harris’ book Five Came Back chronicles the experiences of five filmmakers at the top of their profession—John Ford, George Stevens, John Huston, William Wyler, and Frank Capra—who joined the military to make documentaries and propaganda films. Ford, a Naval Reserve officer who’d sought a transfer to active duty three months before Pearl Harbor, was wounded by shrapnel while filming The Battle of Midway, a strange, impressionist documentary that came out a lot artier than his bosses wanted. Both he and Stevens were present on D-Day, cameras rolling, though much of what they shot was deemed too gruesome for public consumption. Capra made the Why We Fight documentaries, seven short features designed to demonstrate to the troops as well as the public at home the necessity of stopping the Axis powers. Wyler flew with a B-17 crew on bombing raids to shoot his documentary Memphis Belle: The Story of a Flying Fortress.

Arriving at the Dachau death camp with no idea what he’d find, Stevens shot footage that was later edited into a pair of films used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials. Decades would pass before he would speak of the horrors he witnessed there. Stevens’ pre-war phase would be outshined by his postwar career, which included the films Shane, Giant, and The Diary of Anne Frank, but before he went to Europe, he’d been known for his comedies. He never made another one after he got home.

Luhrssen, who co-authored War on the Silver Screen: Shaping America’s Perception of War, also points out that many major stars volunteered for service. The most distinguished of these was Jimmy Stewart, already a box office favorite when he enlisted in the Army in 1941, after first being drafted and rejected as underweight. A licensed pilot, he feared he would be assigned to duty as a flight instructor, or worse, a morale-boosting, troop-entertaining seller of war bonds. He wanted combat, and he pushed until he got it, rising in rank from private to colonel by the time the war ended.

***

Films made years or decades after the war have the benefit of giving writers and directors distance from the events they dramatize and greater freedom to depict what would have been demoralizing or unbearable with the trauma still fresh. Movies that included the Japanese point of view as well as the American perspective, such as 1970’s Tora! Tora! Tora! (an American-Japanese co-production about the Pearl Harbor attack) or 1976’s Midway, a soapy, fictionalized account of the tide-turning air and sea battle, would not have been made during the 1940s.

Like Battle of Britain, both Tora! Tora! Tora! and Midway coupled splashy combat shots with hammy writing and overwrought performances. Midway is also a bit of an anachronism. Its opening titles indicated that it included real combat footage wherever possible, but declined to mention how heavily it relied on material shot for other movies: Its very first frames are right out of the then-32-year-old 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, and it used (comparatively) fresh shots from Battle of Britain and Tora! Tora! Tora! too. Some of its documentary footage dates from later in the war than the May 1942 battle; it includes aircraft that were not yet in service at the time.

Because the movie came out in the middle of the sensitive 1970s, it invested deeply in not one but two maudlin romantic subplots. Charlton Heston—who had served on a B-25 crew in the war—plays Captain Matt Garth, a divorced Navy flier who risks his career to make amends with his estranged son, also a naval aviator, by intervening on behalf of his son’s interned Japanese-American girlfriend and her parents. Apparently that didn’t sufficiently humanize the granite-faced Heston, because the producers took the extraordinary step of hastily writing and shooting additional scenes for the TV version of the film, after Midway had already been released in theaters. The new material gave Garth a girlfriend who agrees to marry him, presumably deepening the tragedy of his sacrifice at the end of the movie, when he crashes and dies while attempting a carrier landing.

The World War II flying movies made closer to the end of the war were better. Sam Wood’s 1948 Command Decision, adapted from William Wister Haines’ novel and stage play, starred Clark Gable as an Army Air Forces brigadier general. The movie de-emphasizes combat scenes, instead exploring the psychic cost of ordering men to their deaths in B-17s and B-29s. (Gable had been awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and an Air Medal for his service as a waist gunner on a B-17.)

Funded by Howard Hughes, Nicholas Ray’s 1951 Flying Leathernecks starred John Wayne as a Marine Corps aviator based loosely on Medal of Honor-winning ace John Lucian Smith. (Wayne had been criticized by his friend and frequent collaborator John Ford for not volunteering for service, as Ford had.) Like the generals in Twelve O’Clock High and Command Decision, he feels the loss of every life under his command, but he must keep this burden hidden—and teach his subordinate, played by Robert Ryan, to do the same. The film is better remembered for its Technicolor photography than for its writing or performances, which are solid but unremarkable.

(It’s not Command Decision or Flying Leathernecks.)

***

The world war II flying movies made during the 21st century have tended to disappoint: 2012’s George Lucas-backed Red Tails, a fictionalized account of the exploits of the 332nd Fighter Group—better known as the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots in the Army Air Forces—was a noble but hammy effort, despite a script by John Ridley, who would go on to win an Oscar for his adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoir 12 Years a Slave. HBO’s 1995 movie The Tuskegee Airmen was a more engaging and sensitive depiction of the struggles against institutionalized racism the 332nd pilots had to wage despite their exemplary record of service: The 450 Tuskegee Airmen earned a total of 850 medals during the war.

Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor, released Memorial Day weekend in 2001, is widely reviled among movie critics, in part because of its overreliance on a love triangle no one cared about. (It’s definitely not Pearl Harbor.) But countless movies used romantic jealousy as a shortcut to winning audiences over during the war, and sometimes it worked: 1941’s A Yank in the R.A.F., also directed by Henry King (who made Twelve O’Clock High eight years later), maintained a light touch while gently suggesting America’s neutral stance had an expiration date. A swaggering American pilot played by Tyrone Power flies a Lockheed Hudson bomber from Canada to England to earn a cool $1,000, but then decides to enlist. Soon he and his commanding officer are competing for the affections of the same woman, played by Betty Grable in her first leading role. Before the war’s end she’d be one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, and a 1943 pin-up photo of her in a one-piece swimsuit became an icon of the era.

A Yank in the R.A.F. couldn’t have been a more “Hollywood” movie. Twentieth Century Fox studio chief Daryl F. Zanuck wrote the script himself (albeit under a pseudonym) and arranged for the participation of the Royal Air Force as well as the U.S. military. He even agreed to the British government’s script note that Power should survive rather than perish heroically in the climactic battle. Filming was done on sound stages and in locations around southern California. Naval Air Station Point Mugu stood in for Dunkirk, not only in this film but in later documentaries that repurposed the fake Dunkirk evacuation created for it. But much of the picture’s aerial combat footage was of real life-or-death dogfights shot by fighters the RAF had equipped with cameras explicitly for the picture. It’s disconcerting to remember you’re likely seeing real deaths occur in a film that’s largely a romantic comedy with musical numbers. Certainly to modern eyes, the subject makes the carefree tone the filmmakers cultivated seem wildly inappropriate.

And yet the film was a hit, arriving in theaters two months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Many imitators followed, featuring heroic Yankee fliers who enlisted in foreign militaries rather than wait for their governments to stop dragging their feet. One of them, the Warner Brothers quickie International Squadron, even starred a Tyrone Power wannabe by the name of Ronald Reagan.

(It’s not A Yank in the R.A.F. or Inter-national Squadron.)

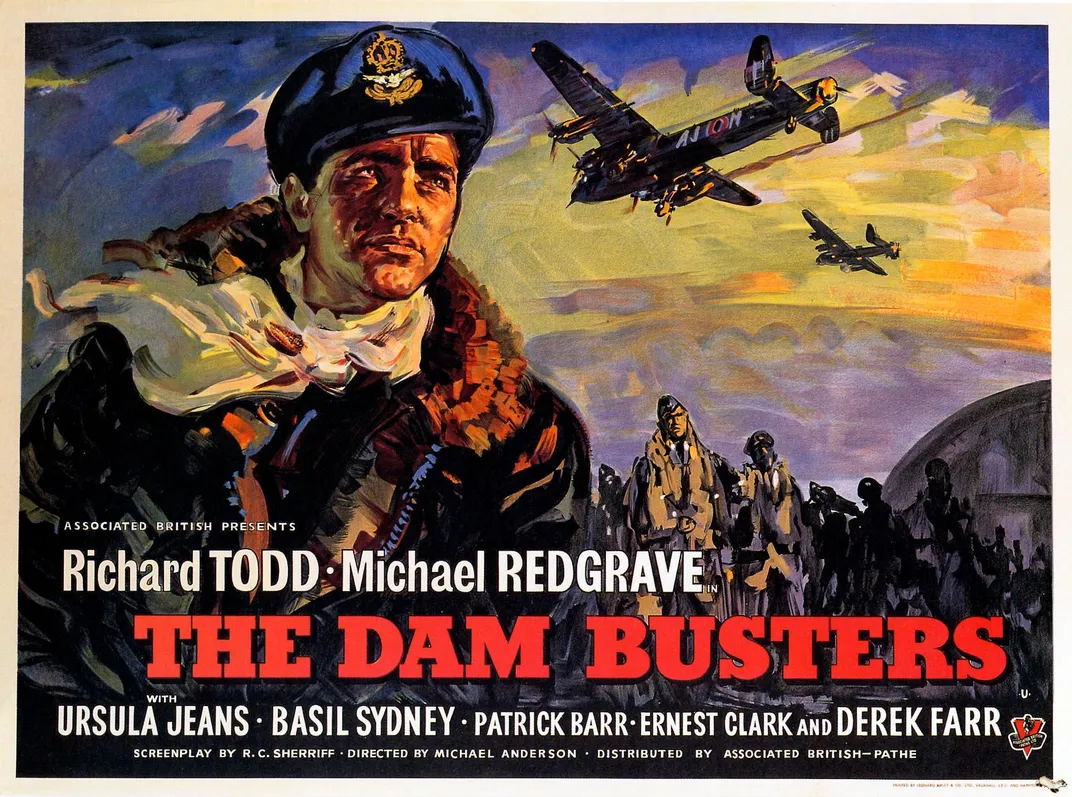

Some World War II flying movies have survived simply on their artistic merit. One is Michael Anderson’s The Dam Busters. Released in 1955, the film tells the story of Operation Chastise, a daring 1943 attack on German dams by the Royal Air Force’s No. 617 Squadron. The operation used a special “bouncing bomb” developed by Barnes Wallace to skip along the surface of the water, eluding torpedo nets on its way to the target. Starring Michael Redgrave as Wallace, the film spends most of its time chronicling the exhausting research and development process that went into the bomb, as well as the pilots’ efforts to perfect the low-altitude flying required to deliver it accurately. Filmed using four RAF Avro Lancaster bombers, the picture’s climactic raid sequence features some unconvincing flak effects, but remains celebrated for its savvy editing and overall quality of suspense. George Lucas has cited The Dam Busters as his inspiration for the fighter attack on the Death Star in Star Wars. Peter Jackson, director of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, has expressed interest in remaking the film.

(And yet The Dam Busters is not the best.)

The British writing-producing-directing duo of Powell and Pressburger (collectively known as “The Archers”) made an astonishing run of films during the war and in the years immediately after. After 1942’s One of Our Aircraft Is Missing, they made what is widely regarded as their greatest picture, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, depicting an unlikely 40-year friendship, through the Boer War and the two world wars, between a British Army officer and a German one. (The German officer emigrates to England as an old man after his sons join the Nazi party.) Today, the 1943 movie seems shockingly mournful, reflective, and timeless, given that it was made in a country under siege.

The Archers’ romantic fantasy A Matter of Life and Death, released in 1946, was set a year earlier. It starred David Niven as the pilot of a flaming and crippled Lancaster bomber who orders his crew to bail out without telling them his own parachute has been destroyed. In what he believes will be the final moments of his life, he has a radio conversation with an air traffic controller (Kim Hunter) and falls in love with the woman. After he finally jumps, sans chute, he wakes up on the beach, mysteriously alive and intact.

(The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is one of the high points of cinema’s first century. But the best film about World War II aviation was not made by The Archers.)

***

If you want to focus less on the flying and choose the film that offers the most sensitive and timely portrayal of the struggles of all returning veterans to reacclimate to peacetime society, the clear choice is William Wyler’s 1946 Best Picture winner, The Best Years of Our Lives. (Among the films it beat out at the Academy Awards—and at the box office, handily—was It’s a Wonderful Life, the first film director Frank Capra and star Jimmy Stewart made after completing their military service.) Aviation is not central to this movie, but it qualifies for the competition because of scenes using castaway airplanes to symbolize the plight of veterans whose country no longer seems to need them.

The movie hauled in nine Academy Awards, including the only two Oscars ever bestowed upon an actor for the same performance. That actor was Harold Russell—only he wasn’t an actor, at least not when Wyler found him. He was a full-time Boston University student and a former Army instructor who’d enlisted the day after Pearl Harbor. While at Camp Mackall, North Carolina, an explosion destroyed both his hands. (He was shooting a training film at the time of the accident. Coincidentally, it occurred on June 6, 1944—the day the Allies invaded Normandy.) Russell had been fitted for a pair of hooks, and Wyler cast him as Homer, a sailor worried that his fiancée, who hasn’t seen him since his accident, won’t want him anymore. On Oscar night, Russell was given an honorary award for “bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans,” in part because the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences assumed the novice performer would not win the competitive Best Supporting Actor for which he’d been nominated. But he did, distinguishing himself among a cast that included Dana Andrews, Frederic March, and Myrna Loy.

The Best Years of Our Lives was a huge commercial success too. That the film was embraced so readily reflected the universality of the problem it depicted. World War II had been a test, wherein both the enemy and the purpose were unambiguous, and every echelon of society did its part. The war ended, and everyone had to find a way to move on with their lives.

The Best Years of Our Lives ends on a note of optimism, but before that it goes to a dark place. Fred, the bombardier played by Andrews, learns that his marriage is failing and decides to leave the town where he’d grown up. He wanders through the aircraft graveyard, then climbs into the nose of a mothballed B-17, reliving his memories of combat. The bomber’s fuselage is painted with the nickname “Round Trip?” Instead of living in the past, Fred plows forward and strikes up a romance with his pal’s daughter Peggy—they share their first kiss at Homer’s wedding.

(Its 1946 audience and the Academy might disagree, but it’s not The Best Years of Our Lives.)

There are at least a few people who might choose A Guy Named Joe, directed by Victor Fleming—who also made The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind—as the best World War II flying movie. The story is more than a little maudlin, but in the spring of 1943 that might have been just what American movie audiences needed. Spencer Tracy plays Pete, a reckless B-25 pilot who’s in love with Dorinda, a civilian flier played by Irene Dunne. After Pete is killed in combat, he finds himself assigned as a guardian angel to trainee pilots, including Ted, played by Van Johnson. Ted eventually falls in love with Dorinda, leaving Pete to get over his feelings of posthumous jealousy and focus on his mission: keeping Ted alive. (“The story of a Guy, a Gal, and a Pal!” the trailer crowed.)

The movie suffers from a languid pace, and its flying scenes aren’t nearly as impressive as those in contemporaneous films. But it captures something few of the movies from the period dared touch: the necessity of accepting devastating loss and carrying on with life.

A Guy Named Joe isn’t the most realistic World War II aviation movie (even discounting the fact it’s about a ghost). It isn’t the most thrilling World War II aviation movie. (The “aerial” shots are mostly of stationary aircraft shot against projected backgrounds.) It’s the World War II aviation movie that told us, with more than two years still left in the war, that a lot of people were going to die, but a lot more people were going to survive. It was an unlikely little hero of a picture and is, I submit to you, the best.