The dollhouse-pink postcard appeared in artists’ inboxes in 2019 with the same prompt that had been sent via snail mail in 1976: “If you consider yourself a feminist, would you respond by using one 8 ½” x 11” page to share your ideas on what feminist art is or could be.”

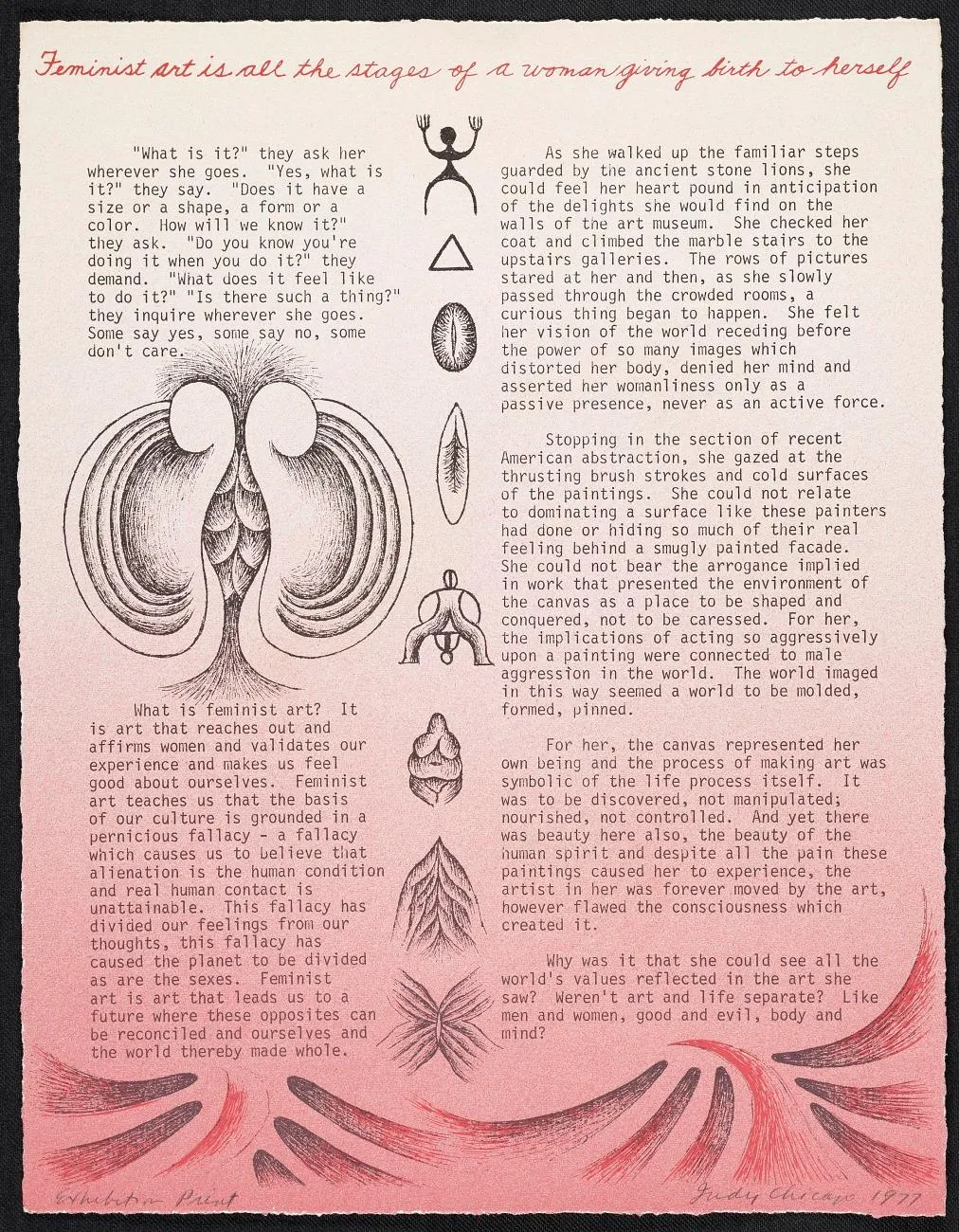

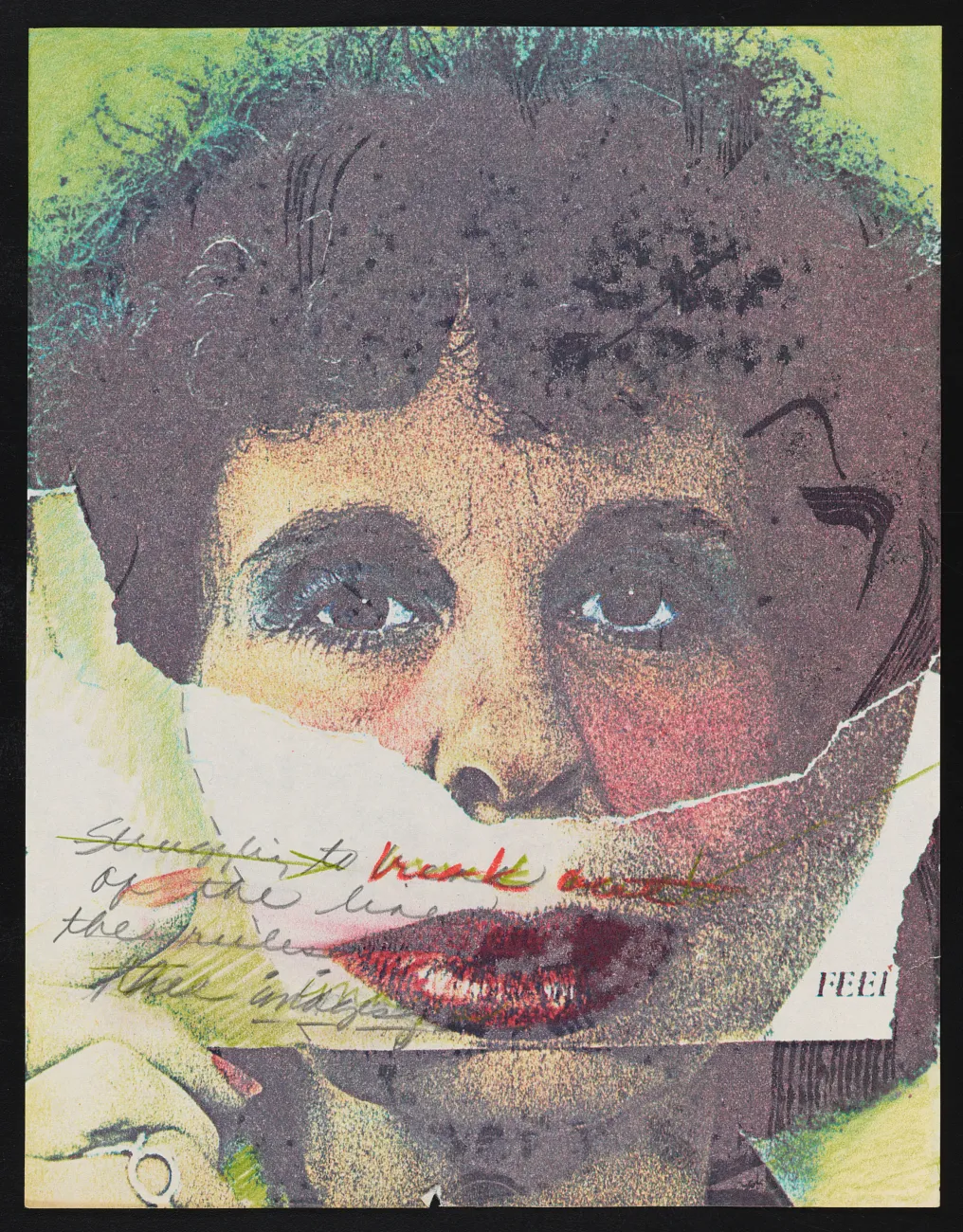

“I haven’t a clue what feminist art is,” scrawled Martha Lesser, one of the 200-plus creatives who responded to the prompt in the 1970s. Others typed out five-paragraph essays, sketched a self-portrait, or even submitted an image of an umbilical cord magnified under a microscope. Their responses became part of a 1977 exhibition in Los Angeles organized by feminist activists for the Woman’s Building.

Remakes are in vogue of late, and 43 years after the West Coast original of “What is Feminist Art?” the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art staged its own “recreation of that exhibition,” says Liza Kirwin, the Archives’ deputy director, by posing the same query to a cohort of artists in 2019. The two sets of answers to the still-relevant central question reveal how society’s understanding of feminism, and feminist art, has changed in some ways and stayed static in others.

The ’70s earned its reputation as a “consciousness-raising era” in the art world and the United States at large, Kirwin says. Against the backdrop of second-wave feminist activism and the sexual revolution, community spaces like the Woman’s Building provided mentorship in a world where formal art training involved a host of mostly male instructors. While feminist art itself obviously predated the decade, art historian Linda Nochlin’s influential 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Woman Artists? and Judy Chicago’s controversial and very vulvic installation The Dinner Party (1974-79) exemplify the surge in art that directly pondered women’s rights and roles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/37/8a377501-bd54-4fc6-bc44-2208ac567f12/2_mendieta.jpg)

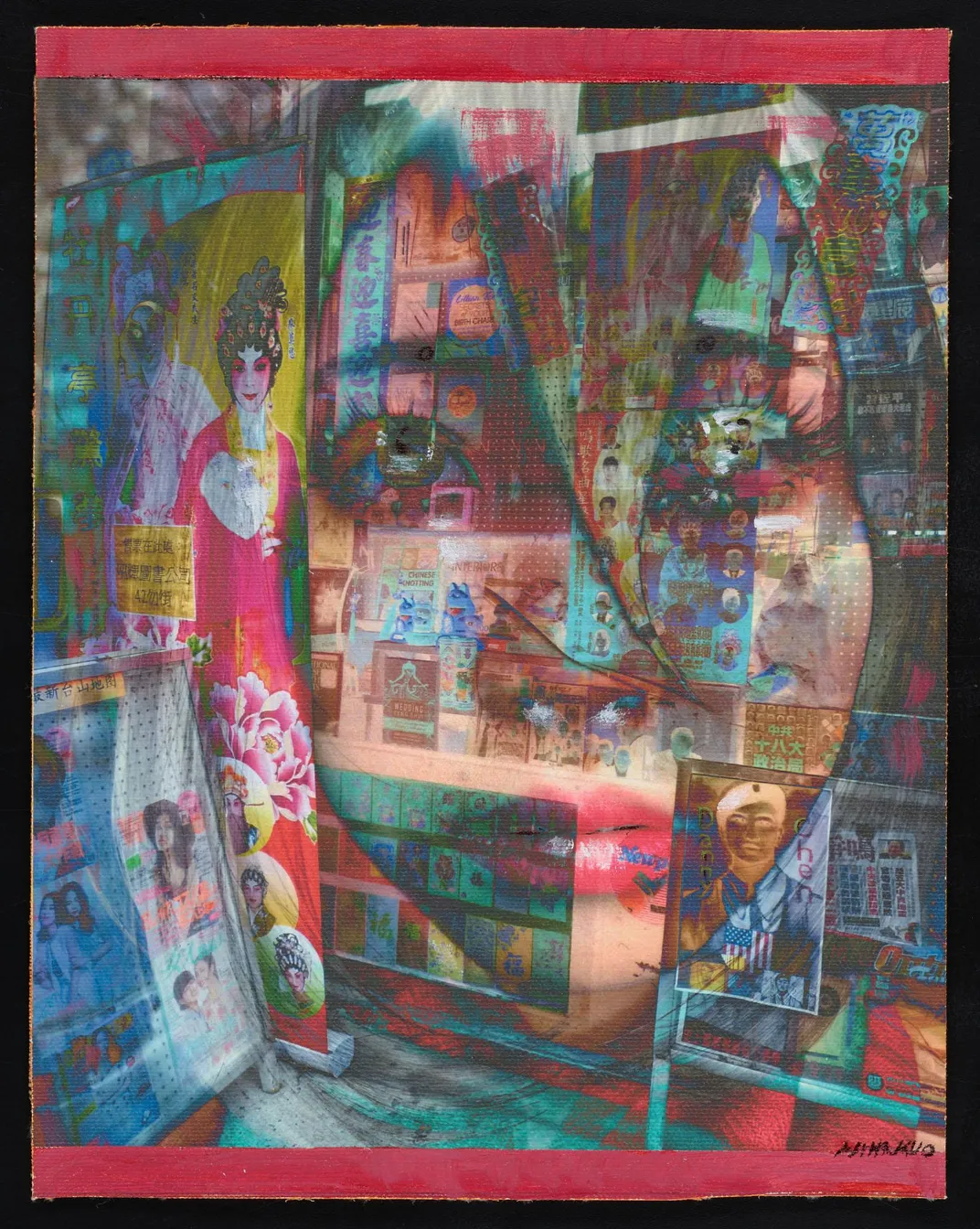

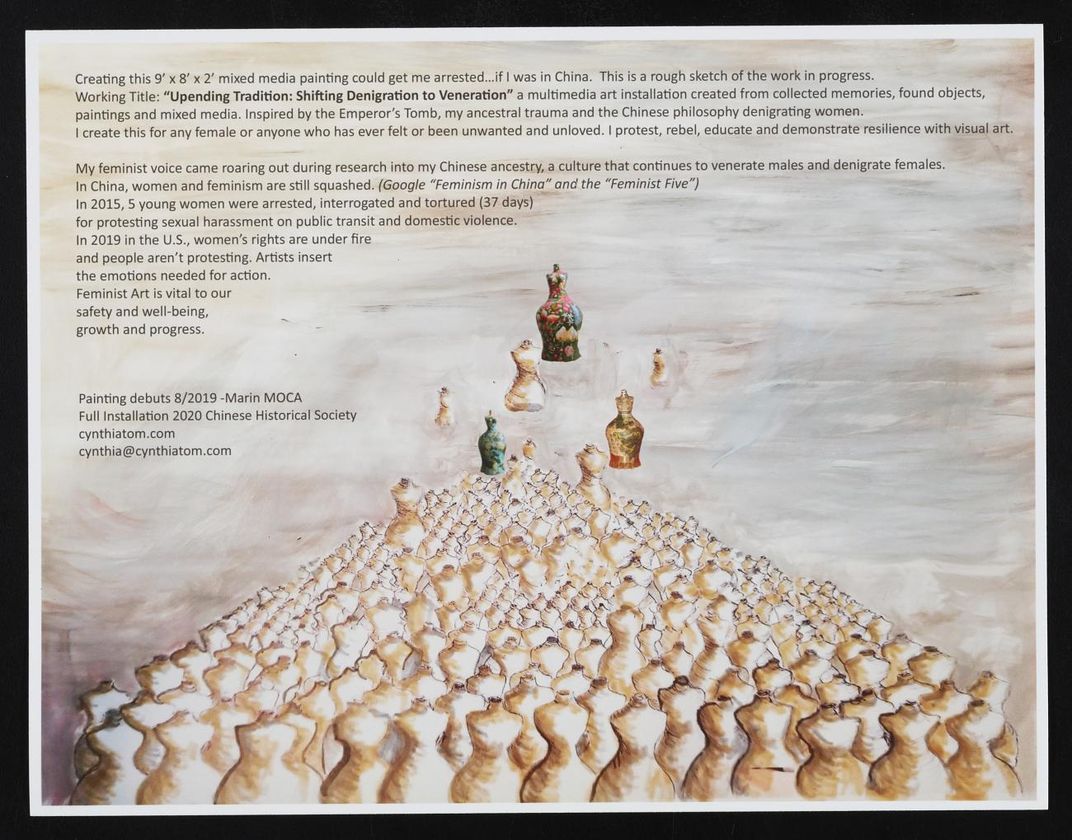

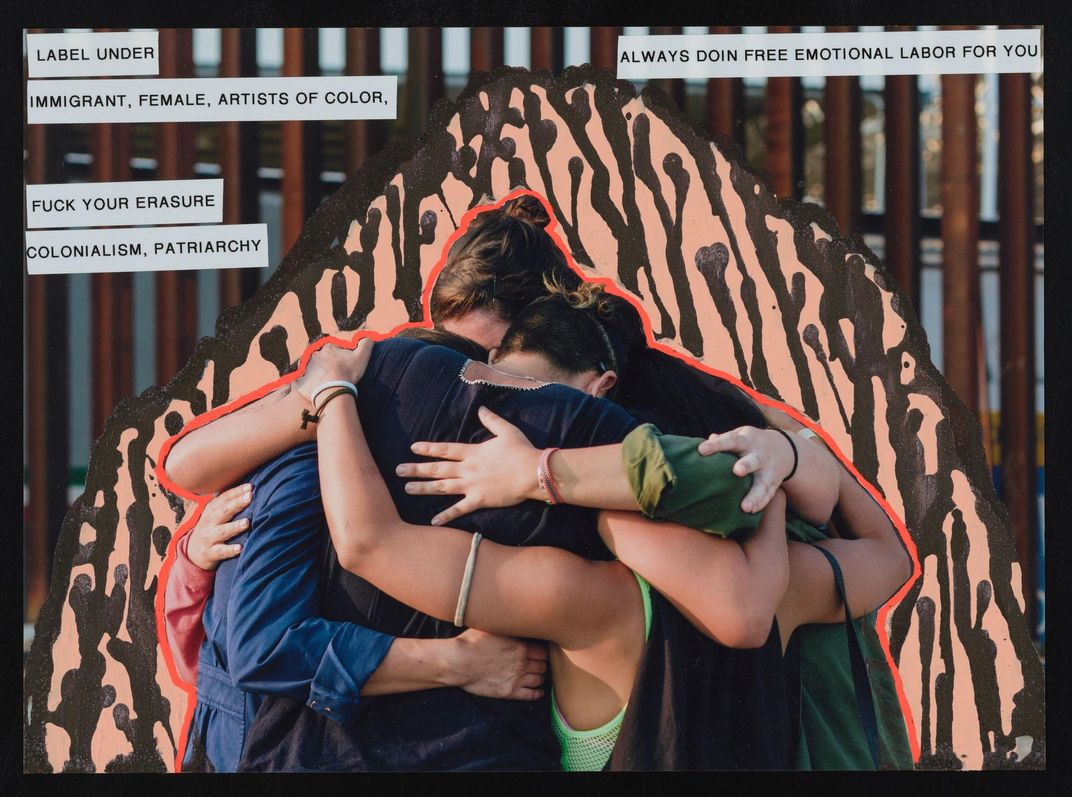

For the exhibition’s present-day reincarnation, the Archives of American Art wanted to address a flaw in the original show to ensure that a more representative cross section of artists from the U.S. and abroad participated. To this end, the show’s curator, Mary Savig, assembled an outside advisory group of influential artists, curators and academics whose professional work involves highlighting marginalized artists’ work.

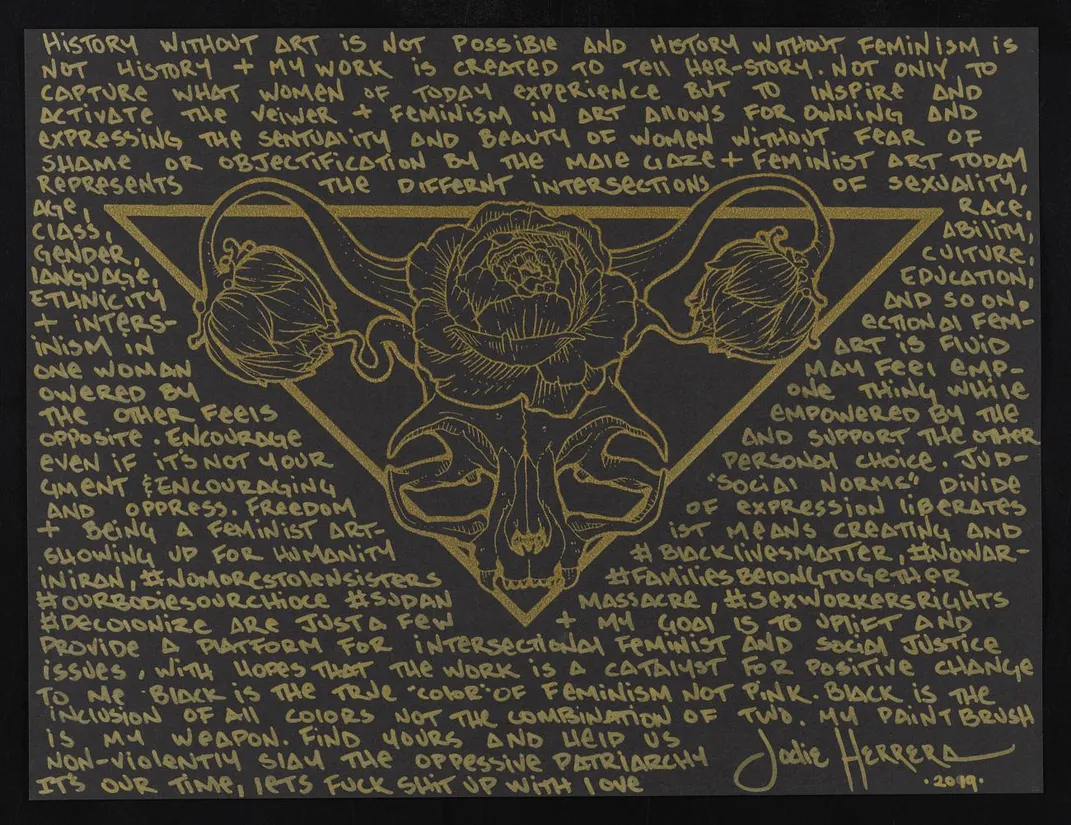

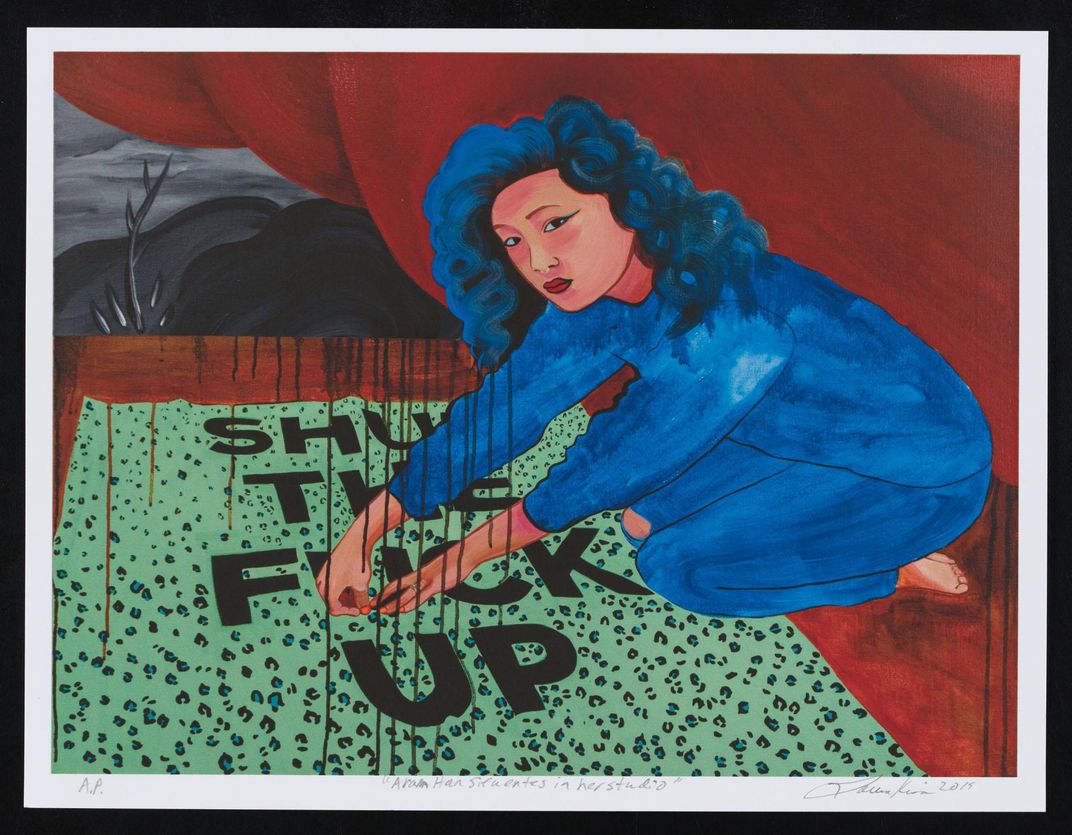

The committee’s roster of visual artists was less white than the ’70s cohort, although still largely (but not exclusively) female-identifying. Some of the original respondents also had the chance to contemplate the question for a second time. The exhibition also presented two exciting firsts for the Archives of American Art, Kirwin says. The wall text appears in both English and Spanish, and the Archives had the opportunity to solicit new materials from a younger group of artists. This contemporary cohort of artists sent 75 answers, among them: a bunch of blue sparkling spirals, typed or handwritten notes, lipstick-smeared paper, a painting of another artist in the studio, decidedly modern screenshots of iPhone messages and more.

Kirwin explains that the show puts the two sets of meditations on feminist art—from 1976-77 and 2019—“in conversation with another.” While the walls are stamped with a few choice quotes from the artwork and papers on display, there’s no one definition of “feminism” provided. Instead the point is for the viewer to take in the artists’ perspectives and draw their own conclusions about what “feminist art” means. “We wanted to really minimize the curatorial point of view in this exhibition,” Kirwin remarks.

Nevertheless, here’s some useful context: Feminism and the “women’s movement” have increased in popularity since the first showing of “What is Feminist Art?” In a 1986 Gallup poll, only around 10 percent of women identified as “strong” feminists, and nearly a third said they wouldn’t consider themselves feminists. Fast-forward to 2016, and six out of every ten women pronounced themselves either a “strong feminist” or “feminist” in a Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation poll.

Despite what the numbers suggest is a growing mainstreaming of feminism, Kirwin says she noticed “a frustration” in some of the reflections the original artists provided in 2019, the second time they’d been asked (formally, at least) to define feminist art. Harmony Hammond, a leading figure in the movement, proclaimed that feminist art was “STILL DANGEROUS” in bold lettering on her current 8.5-by-11-inch sheet. In the original show, she’d called it “Dangerous,” too, but nestled that adjective in a longer letter and not written it in such large, capital letters.

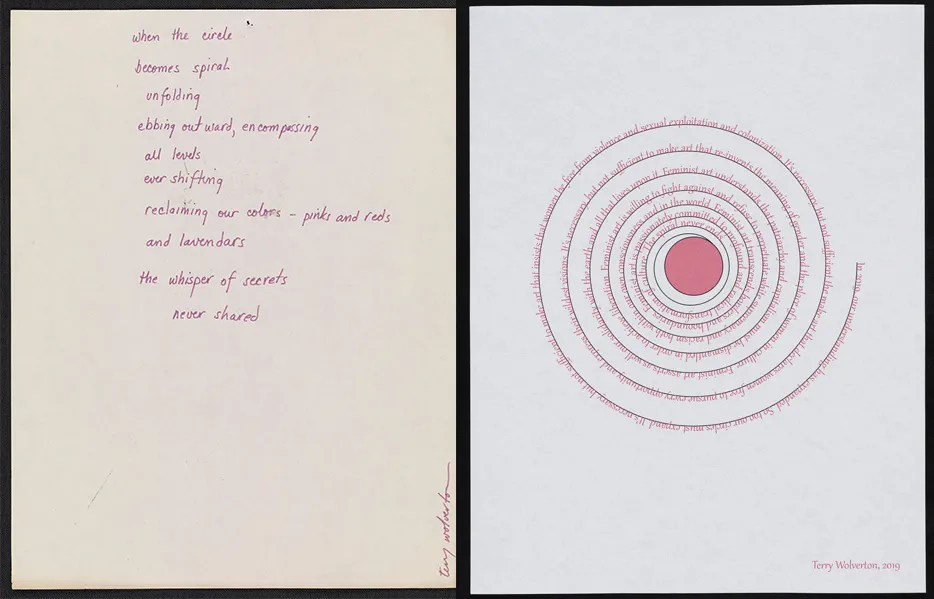

Other 2019 responses emphasized the importance of intersectionality—understanding the interconnection of various forms of discrimination—in today’s feminist art. “In 2019, our understanding has expanded. . . Feminist art is willing to fight against and refuse to perpetuate white supremacy and racism,” wrote poet Terry Wolverton, her words arranged in a pink spiral. Potter Nora Naranjo Morse explained that the line of Tewa Pueblo women she comes from exemplified feminism without being conscious of the Western definition of the term. In typed white letters on a background of inky black paper, textile and visual artist LJ Roberts objected to the project’s lack of honoraria, arguing that unpaid art takes time away from other important artistic pursuits: “As a queer, non gender-conforming, non-binary person…being asked to produce work for free undermines critical goals that feminist art aims to achieve.”

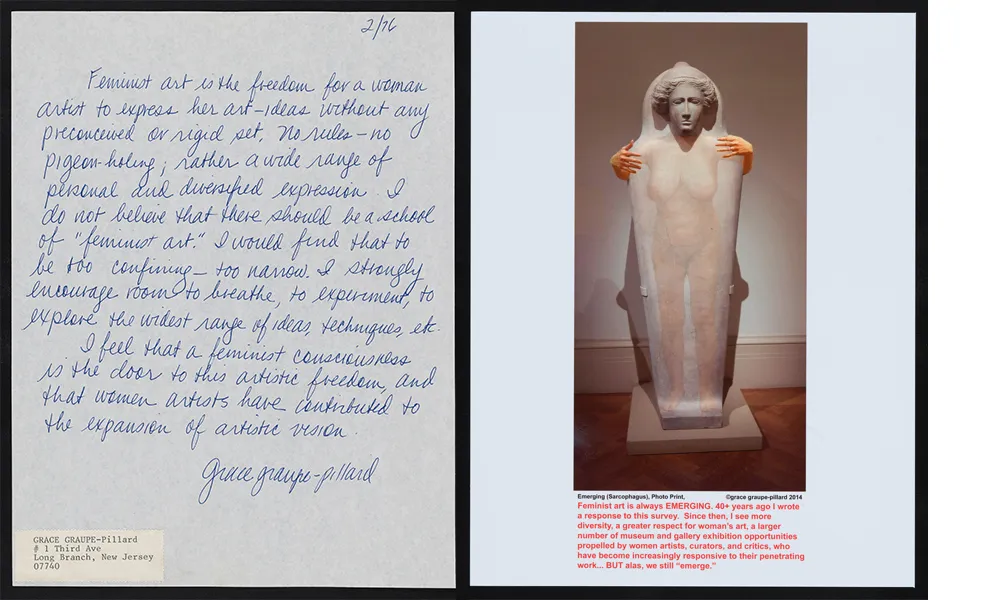

Other themes stood out in the original and contemporary 8.5-by-11 statements. Howardera Pindell’s 2019 statement that “Feminist artists are free from feeling that they have to imitate Euro/American male culture in form, style, media ect.,” echoes Grace Graupe-Pillard’s 1976 wish for “No rules—no pigeonholing” of art created by feminists. And Joyce Kozloff’s 21st-century answer reiterated the definition the critic Linda Nochlin offered back in 1970: “Feminism is justice.”

The exhibition, with its wide array of responses, aims to be thought-provoking. Asked what she hopes visitors leave the gallery thinking about, Kirwin replies simply, “I hope they ponder the question.”

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. “What is Feminist Art: Then and Now” is scheduled to be on view through November 29, 2020 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery on the first floor of the Old Patent Office Building at 8th and F Streets in Washington, D.C., also home to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. Check listings for updates. The exhibition is a project of the Smithsonian's American Women's History Initiative.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/20/22201fb7-8f1e-4a8c-9e65-bb27c599f21c/feminist-art-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/02/32022622-2350-4f33-847f-2fb851d3d820/aaa_womabuil_69214.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/5e/f15e1e36-625d-42ff-9ef3-5e3d81216aa9/aaa-aaa_whatisfe_69055.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/c7/82c75bc5-fcc2-4619-b7a7-c4d00065a9a8/arlene.jpg)