How Much Did Wernher von Braun Know, and When Did He Know It?

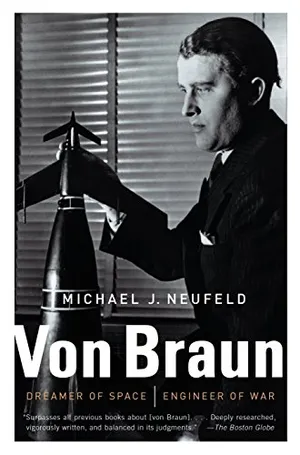

Michael J. Neufeld talks about his new book, Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/c4/98c4ed4e-fcd8-4d86-b30d-4c275afeab7a/bundesarchiv_bild_146-1978-anh024-03_peenemunde_dornberger_olbricht_brandt_v_braun_1.jpg)

Michael Neufeld, who chairs the Space History Division at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, recently spoke with A&S Associate Editor Diane Tedeschi about his extensively researched new book, Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War (Knopf, 2007). A rising star in the German army’s rocket program, Wernher von Braun led the development of the seminal V-2 missile and was a loyal follower of the Third Reich. After the war, he reinvented himself as a leader of the U.S. space program. But questions about his complicity in using slave labor to build the V-2 have never gone away.

A&S: What kinds of choices did von Braun have? Was there any way he could have repudiated the use of slave labor and yet still carried on his work as a rocket engineer?

Neufeld: That’s been the traditional kind of defense: that he was trapped, that he couldn’t do anything. The problem with that is that it makes him look like someone who really didn’t want to be in the Third Reich—someone who didn’t like the Nazis. But all the evidence I have is that he was quite comfortable with the Nazis and the Third Reich until late in the war. And it was only in the very last year or two of the war—through a combination of his last encounter with Hitler, witnessing concentration camp labor, but above all his own arrest by the Gestapo—that he became disillusioned about this regime that he was working for. Up to that time, although not enthused about joining the party and the SS, he’d been a fairly loyal member of the Third Reich and in some sense or other, a Nazi, if not an ideological one or one who cared about the race theory very much.

What choice did he have? Well, by the time he found himself in the middle of concentration camp labor, it’s probably true that he didn’t have many choices. And my argument in the book is, in many ways, he had sleep-walked into a Faustian bargain—that he had worked with this regime without thinking what it meant to work for the Third Reich and for the Nazi regime. And he bears some responsibility for his own actions, therefore. In the case of concentration camp labor, there wasn’t much he could do to help. But he still bears some moral responsibility for being in the middle of that situation, seeing the concentration camp labor personally, face to face. Seeing the horrible conditions and continuing to work. And I mean, he not just continued to work, he continued to work day and night energetically for that program with total commitment—even after being arrested by the Gestapo.

There’s no question that he knew about the slave labor?

He was in the underground plant at least 12 to 15 times. As I found out in the testimony that he gave for a war crimes trial in West Germany in 1969, he mentioned that he’d been through the underground sleeping quarters, which had been built in the tunnels in late 1943 for the concentration camp workers because the above-ground camp hadn’t been finished or hadn’t even really been started. And those underground accommodations were horrific. And he walked through that area and through the mining area.

I’d like to think that he would have been deeply affected by the horrific sights that he witnessed, and yet if he had objected to these deplorable conditions, I can’t imagine his superiors saying, “You’re right, Wernher. Let’s put a stop to this.”

I agree that he didn’t have much, if any, power. And that to say very much of anything was dangerous for him personally. But, again, I would emphasize his personal responsibility for having gone along with this regime, in its aggressive war plans, in building weapons for Hitler, in being a loyal member of the Third Reich, and being a member of the party and the SS. And being personally responsible for using concentration camp labor.

We like to have everything resolved black, white; hero, villain, and he’s a complicated, difficult character, and I would agree that there’s a lot of room for ethical debate about what you can hold him responsible for and what you could have expected him to do.

I really like your term sleep-walking his way into a Faustian bargain, because I can picture him in the beginning having these aspirations and having this great mind and thinking, Why not work for the army? And then things got more and more horrific, and then he would have had to make a really decisive move to say, “I’m going to get out of this. Even at the risk of arrest and persecution.

By the time he got to the end of World War II, when he sort of very belatedly woke up to what kind of system he was working for, he really didn’t have any choice anymore. I mean, he wasn’t in a position to quit, but it must be remembered that he didn’t want to quit. He was loyal to the army. He was a German nationalist. As demonstrated by the things he said to his American interrogators after the war, he was pretty Nazified in the way he thought about the world. Now he was influenced by this regime. He came out of a right-wing conservative family, and it was only very late that he woke up to what he was doing. But at the beginning, one of the most interesting things I discovered in doing this was that he was obsessed with going into space personally. This dream he had from the 1920s onward was not just: Space is good for the human race, we should explore space. This was: I want to go into space. I want to lead an expedition to land on the moon. He was driven by that dream. All the way through, from the 1920s at least into the 1950s, when he finally probably had to admit that he wasn’t going to be young enough to be doing that kind of thing. That he would have to be on the ground. He still hoped to go into space. He talked about that even in the 1970s: that he hoped to go up on the space shuttle. So this dream of flying into space was the thing that drove him, and it caused him to be all too willing to accept money and resources from whomever came along and said, “Here, build rockets. Just do it for us. Do it our way.” So he walked into this. And of course the fact is, it was the army. And he came from this conservative Prussian aristocratic family; he was actually a Prussian baron. His family had a lot of army officers in it. His father was a reserve officer in the Kaiser reich. So going into the army was no problem at all.

Then the Nazis came to power, and things got better for the military. And Hitler gave more money to the army. And the whole rocket project took off in an amazing way. Everything as far as von Braun was concerned was just going great. And that continued well on to the middle of the war. And it is not that in the middle of the war, suddenly, he knew he was developing rockets as weapons; he knew that from the very early days. But suddenly the V-2 had to be produced. It was not enough any longer to be spending huge sums of the Reich’s money for experimentation. This weapon had to be deployed. And so starting around 1942, political intervention into the program got much heavier. And they were forced to put that V-2 into production and push it into deployment because they needed it. The war was starting to go bad, and people were grasping at straws, including Hitler, and they decided they really wanted this rocket weapon.

Did von Braun ever express remorse about the use of slave labor or about any of the other horrors that transpired under the Nazi regime?

After the war, like so many others, he said, “I didn’t know about the Holocaust.” He also came to the realization that Hitler was an evil person. So he certainly distanced himself from that. And late in his life, in the 1960s and’70s, he did express some remorse in letters about the concentration camp prisoners. To me, it’s better than nothing, but it’s not very good. There’s no great sense of guilt there. There always seemed to be more than anything else, a kind of distancing. That it wasn’t really his problem, his responsibility. There wasn’t really anything he could do about it. And it wasn’t his idea. But there was never any acceptance of personal responsibility—for any of it. It was always something done by the Nazis, that he allegedly did not have anything to do with. He went out of his way to conceal this. And when you look at him in the 1950s, when he rose to fame in the United States, he had to provide a story about his Third Reich career. He did several interviews and memoirs. And he quite blithely went forward with a story about Peenemunde that completely left concentration camp labor out—or reduced it to a tiny afterthought. He created a story about his career in the Third Reich that almost totally left that out. Obviously, the fact that he’d been in the SS was completely suppressed. And the U.S. government needed him. We found him very useful, and decided to keep a lot of these things secret.

Do you think von Braun bought into the idea of racial superiority?

I don’t think he was interested in race theory. And I find no evidence of him being an anti-Semite. But I do find, even in his own words, in a letter he wrote in 1971, that he was really kind of oblivious to the persecution of the German-Jewish population. Like so many others, he just wanted to wish it away, explain it away, because so many other things about the Third Reich were things he liked. So he just wanted to sort of avert his eyes and forget about it. I mean everything was going great for him personally. Money and power and resources at an incredibly early age. He was 25 years old; he had 400 people working for him. He had 5,000 people working for him when he was 30 years old. I mean he was incredibly talented. His real talent was not being a scientist or an engineer. He had a Ph.D. in physics, but he really was an engineer. But it was engineering management: He had this talent for managing large engineering organizations. Not only managing but also constructing these systems for building really exotic new technologies. And he had a vision of how to construct this giant engineering team to do something that no one had ever done before. And that was his real genius. In terms of nuts and bolts invention of technology, he wasn’t any smarter than a lot of people. And probably wasn’t even as good as a lot of other people. But as an engineering manager, he had a very rare talent.

What made him such a great manager of these large-scale programs?

It was a combination of talents: One was obviously that he had the fundamental science and engineering background. That he understood what he was talking about. He wasn’t just a figurehead manager type. He really had the engineering and science background.

Number two was that he was enormously charming and charismatic. People just wanted to follow him. He inspired confidence. He was very diplomatic. When he needed to be, he was very pragmatic. When something didn’t work out, he’d try it a different way. He had a skill for dealing with people that was really uncommon.

The photographs from the book show that von Braun, especially in his younger days, was stunningly handsome.

After the war, a British correspondent described him: “As handsome as a film star—and he knows it.” He was kind of a ladies’ man during the Third Reich. He was extremely good-looking, and that didn’t hurt, obviously, with everything else he had going for him.

In terms of his contributions to the development of rocket technology, how do you place von Braun?

I never liked him very much as a person because I was repulsed by the moral compromises [he made during] the Third Reich, but in the end I had to conclude that he was the most important rocket engineer and space advocate of the 20th century. If there’s any argument to oppose my picking of von Braun as Number One, it would be an argument you could make for Sergei Korolev because Korolev had all these firsts: I mean he’s the guy who put the first satellite into space, the first animal into orbit, the first object to hit the moon, the first object to fly by the moon, the first object to photograph the far side of the moon, the first man, the first woman, etc. So Korolev, in terms of space firsts, really is Number One.

But von Braun was the most influential person of the 20th century because of the V-2, above all. Because the V-2 was so influential in the development of rocketry in the Soviet Union as well as the United States and also Britain and France and other places. And then after that great accomplishment (even though it was a bad weapon, it was a great breakthrough in rocketry), he came to the United States and he proceeded to sell [Americans], and by extension the whole western world, on the feasibility of going into space, through Collier’s and Disney. And he was key to launching the first American satellite. And he was a key participant in landing humans on the moon: [his] role in the Saturn program, the development of the launch vehicles for the lunar landings was very important. The combination of all these achievements, makes me rate him Number One for the space advocate and rocket engineer of the 20th century.

How well did von Braun go about rebuilding a new life in the United States?

He and about 120 of his associates were brought over as a group from Peenemunde. And they were working for the U.S. Army, so in that sense, he didn’t have to find his way or find a new job. The Army brought him over; the Army gave him a job. What was frustrating [for him] in the early years was that after World War II, the public wanted to demobilize. The Cold War started after only a couple years, but the U.S. was very reluctant to invest in a new arms race, and there just wasn’t much money being invested in rocketry.

[Von Braun’s group] had this small project in Fort Bliss; they were in El Paso, Texas, for four to five years. That’s when he decided to start writing a novel called Mars Project. He didn't want to write something that could be labeled a Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon joke. Although the novel didn’t work out, in the end, it resulted in the Collier’s magazine articles starting in 1952, and that’s when he made his breakthrough.

It is kind of amazing—he could have spent the rest of his life as an Army rocket guy. Although he had that foundation in which to live, he constructed his own career as a great public figure in the 1950s. He was the one responsible for making himself into a household name. Ward Kimball at Disney suggested to Walt Disney that [they] ought to do something about space, because [Kimball] had been reading the Collier’s articles. So that led to von Braun appearing in the Disney TV program—in three major space shows, 1955 and 1957 they were broadcast.

So he assimilated fairly easily into American culture?

Yeah, he assimilated fairly quickly. His English was a little rough for a few years. One of the funny stories to tell about him is when he went to the Pentagon in the late ’40s, people would be embarrassed when he spoke because he spoke this combination of GI slang with a lot of swear words. That’s how he learned his English.

In the epilogue from your book you write that President Jimmy Carter released a statement after von Braun’s death that included the following: “Not just the people of our nation, but all the people of the world have profited from his work.”

Your thoughts?

Well, the Carter statement is a very interesting case of how von Braun was viewed during the Cold War—basically as a benevolent space pioneer. The fact is his work is much more ambiguous and two-sided. Of course the whole story of the concentration camp labor hadn’t really come out in the United States yet.

“Nazi Villain or Space Hero” is the title of one paper I’ve been giving. Everybody wants to reduce him to a stereotype: Either he’s the great pioneer of space or he is a bad Nazi with jackboots who’s tromping on concentration camp prisoners. I find him to be a much more ambiguous figure—much more complicated.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.