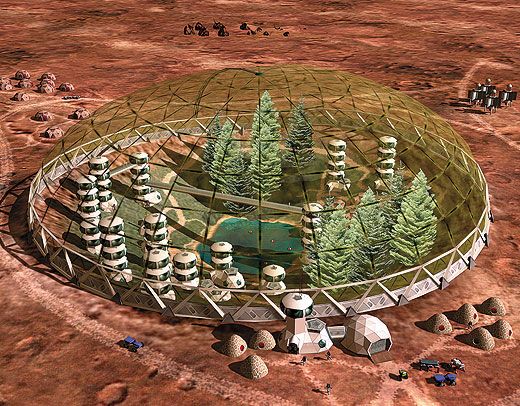

First Neighborhood on Mars

The creator of The Sims imagines us on the Red Planet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/first-neighborhood-on-mars-aug-2012-1_FLASH.jpg)

As the inventor of SimCity, The Sims, and other titles in the hugely popular series of interactive “god game” simulations, Will Wright has had to think a lot about how societies evolve. More recently, the 52-year-old co-founder of Maxis has taken the concept to the next level with Spore, which lets video gamers direct the evolution of life itself. So when we wanted someone to speculate about how the first communities on Mars might develop, we thought: Who better than Will Wright?

Ours was not a completely idle speculation. Last year, SpaceX founder Elon Musk made the business case for Mars this way: Reduce the cost of moving there to “around the cost of a middle-class home in California,” which he estimated at $500,000. With eight billion people on Earth by mid-century, Musk figured that one in a million would prefer Mars to California, and those would “be part of a founding team of a new civilization.”

Here’s how Wright pictures Marstown, pop. 8,000, in 2047:

From above, the terrain looked barren and rugged as the shuttle approached the landing zone near the base of the ancient volcano. At 200 feet, the thrusters began to arrest the ballistic fall of the craft, as a cloud of light dust kicked up into the air. For the first time, Sasha saw the entrance to her new home, Nili Patera, where she would in all likelihood spend the rest of her life. All that was visible on the surface was a 30-meter block with airlocks, set into the side of the volcano. Behind that wall, an extensive network of subterranean lava tubes snaked around the base of the mountain. All openings to the surface had been blocked and the interior walls sealed so the tunnels could be made habitable for the colonists.

The passengers exited the shuttle through an inflated tunnel that reached 50 meters into the airlock complex. As new colonists, they would spend two weeks in the quarantine area, near the outer perimeter of the colony network, ensuring that they were not carrying any diseases.

Like most colonists, Sasha had made the decision to move to Mars for the sake of her descendants. Seeing only limited opportunities on Earth and having a strong sense of adventure and duty, she had been captivated by the ratification of the Mars Development Treaty of 2032. Dwindling natural resources and massive environmental disruption had encouraged politicians on Earth to look to Mars as a long-term lifeboat, another foothold for humanity in the face of an uncertain future.

The Mars Treaty essentially privatized about half of the Martian surface, rewarding those willing to relocate there with huge plots of land. While that land was nearly worthless today, the hope they all carried was that one day it would be a valuable legacy to pass on to their children and grandchildren.

Sasha was in the third wave of colonists; the first group of 500 had been transported to Mars eight years earlier. The colony now numbered about 8,000, the primary limits to the population being the cost of transportation from Earth—which was covered by the Mars Development Corporation (MDC)—and the extent of the hydroponic gardens within the tube complex. The MDC represented a consortium of investors from national governments and international funds (vying for long-term territorial and mineral rights) and individual billionaires (with more idealistic motives).

Following an uneventful quarantine period, Sasha was finally moved into her assigned “apartment.” That was a generous term for the 130-square-foot cubbyhole that would be her only private space in the colony. She was assigned to live in the singles district. If she decided to enter into a co-habitation contract with another colony member, they would be entitled to a larger space.

Having children was another matter. While MDC was willing to subsidize the transportation and housing of new colonists (between the ages of 25 to 30, with long work lives ahead of them), the corporation was much more reluctant to permit the additional resource burden of offspring. Only the most productive members of the colony got this award: an official birth license.

Sasha would be working in the bota-genetic labs initially. Here, hundreds of strains of Earth plants were being slowly engineered to increase their adaptation to Martian conditions. It had been decided decades earlier that it was more cost-effective to terraform only small areas of Mars at first, while at the same time adapting imported life-forms (first plants, then animals and humans) to the new conditions. Over time, the crops, animals, and people would truly become Martians, fully suited to their new homeworld. That was the plan, at least; the process would take many generations.

The culture of the colony was, on the surface, one of fierce independence. The unspoken truth was that the residents were still dependent on Earth, and far from self-sufficient. The social situation in the colony felt similar to that of any small town on Earth. News traveled fast, gossip was the coin of the realm, and secrets did not stay secret for long.

Sasha adjusted nicely to the strange new environment, her determination and boldness serving her well. She eventually found a life partner who worked in the terraforming group, and they were very happy in each other’s company, which helped a lot because their home was only slightly larger than a closet. Sasha’s quick thinking during the airlock breach of 2052 saved many lives in the colony, and she and her partner were rewarded with a birth license. The following year they conceived their first child, Anya.

While still in the womb, their daughter received gene therapy, an option her parents chose. She would be among the first people adapted, however slightly, to the conditions on Mars. Anya’s bones would be longer and thinner, her lungs larger and more resistant to carbon dioxide poisoning, her metabolism more attuned to the locally grown hydroponic food, and her physiology changed in other small ways.

Anya and others of her generation would be the first true Martians. Homo martialis was born.

Game designer Will Wright co-founded Maxis and his current company, Stupid Fun Club. His creations include SimCity and The Sims.