How Things Work: Space Fence

The new early-warning system to protect spacecraft from orbiting junk.

In early 2019, U.S. Air Force Space Command will activate a powerful new space surveillance radar to replace an array, shut down in 2013, that had served since the age of Sputnik. Now under construction, the new array will operate in a band of frequencies 1,000 times higher than those covered by the previous system, activated in 1961. Shorter wavelengths make the new radar more precise; it will be able to detect targets as small as about four inches in diameter (as opposed to the old 30-inch limit) and will expand the catalog of space debris tracked by the Space Command from about 23,000 objects to 200,000.

“Back in the [early] ’60s they didn’t have a space debris problem,” says Steve Bruce, vice president of advanced systems at Lockheed Martin, the company creating the Space Fence. “They just wanted to figure out if something was flying over the continental U.S.” Today, space junk is a serious threat to satellites: NASA estimates that half a million particles with diameters between one and 10 centimeters (about four inches) are orbiting Earth, with average impact speeds above 22,000 mph.

The concept of a fence arose from the design of the earlier system: a narrow beam that triggers an alert when an object flies through. “Our system has the ability to be steered electronically,” says Bruce. “We track [the object] and immediately create an orbit determination.” The fence will join a surveillance network of radar, telescopes, and a satellite.

When the Space Fence is completed on Kwajalein Atoll, 2,100 miles southwest of Hawaii, it will serve as the first stage in a production line feeding data to the Joint Space Operations Center at California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base. When the radar detects an object orbiting Earth, it reports to computers that characterize the object and calculate its trajectory. If the item matches one already in the catalog, its record is simply updated; a new object is tracked until its orbit can be estimated and is then added to the catalog.

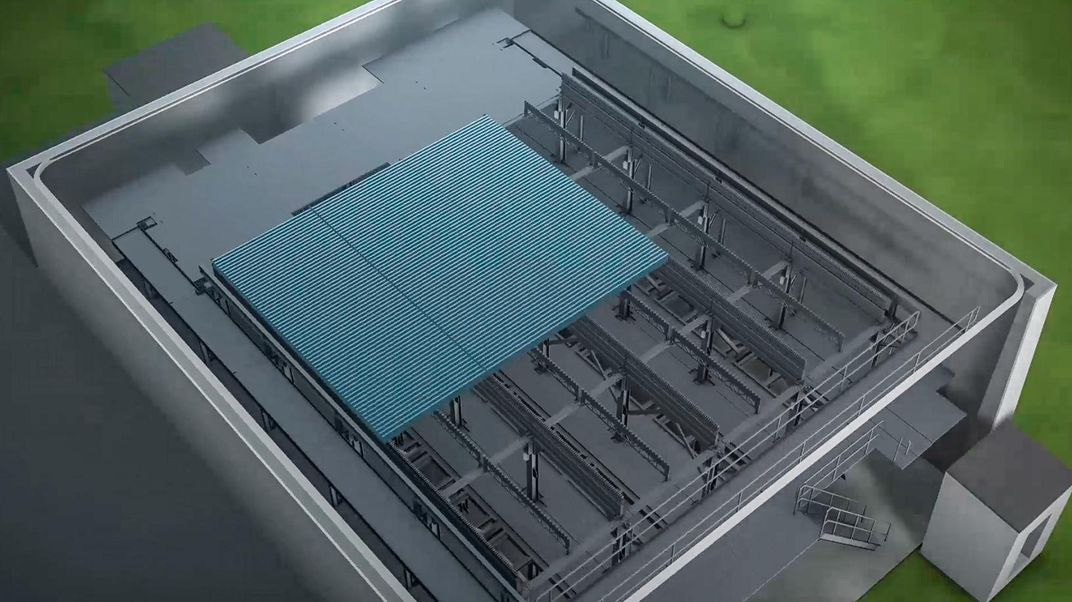

The new S-band phased-array radar will have tens of thousands of transmitters and hundreds of thousands of receivers, supported by structures capable of withstanding seismic activity. One of the largest S-band arrays in the world, the receiver alone measures 7,000 square feet. The transmitter is 2,000 square feet. Both will be enclosed in buildings with roofs of electronically transparent Kevlar. Within each element, gallium nitride semiconductors amplify the radar’s power. In a phased array, the elements can be pulsed separately, so the installation will be able to simultaneously search for and track individual objects.

Airspace above the array will be restricted to air travel, though the radar is expected not to harm birds because exposure times will be short, though personnel will monitor bird activity.

The Space Fence is one part of a space surveillance network that includes a Space Based Space Surveillance satellite, which collects information about the orbiting objects and particles from a 390-mile-altitude orbit, and the Space Surveillance Telescope in Australia. The 180,000-pound telescope, funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and developed by MIT’s Lincoln Labs, will find faint objects in geosynchronous orbit up to 22,000 miles high. The telescope, satellite, and fence all feed data into the surveillance network, providing faster warning that space debris could collide with the International Space Station or satellites in low Earth orbit.