The Nine Lives of an Apollo Moon Lander

How LM-2 came to impersonate the Apollo 11 lunar module.

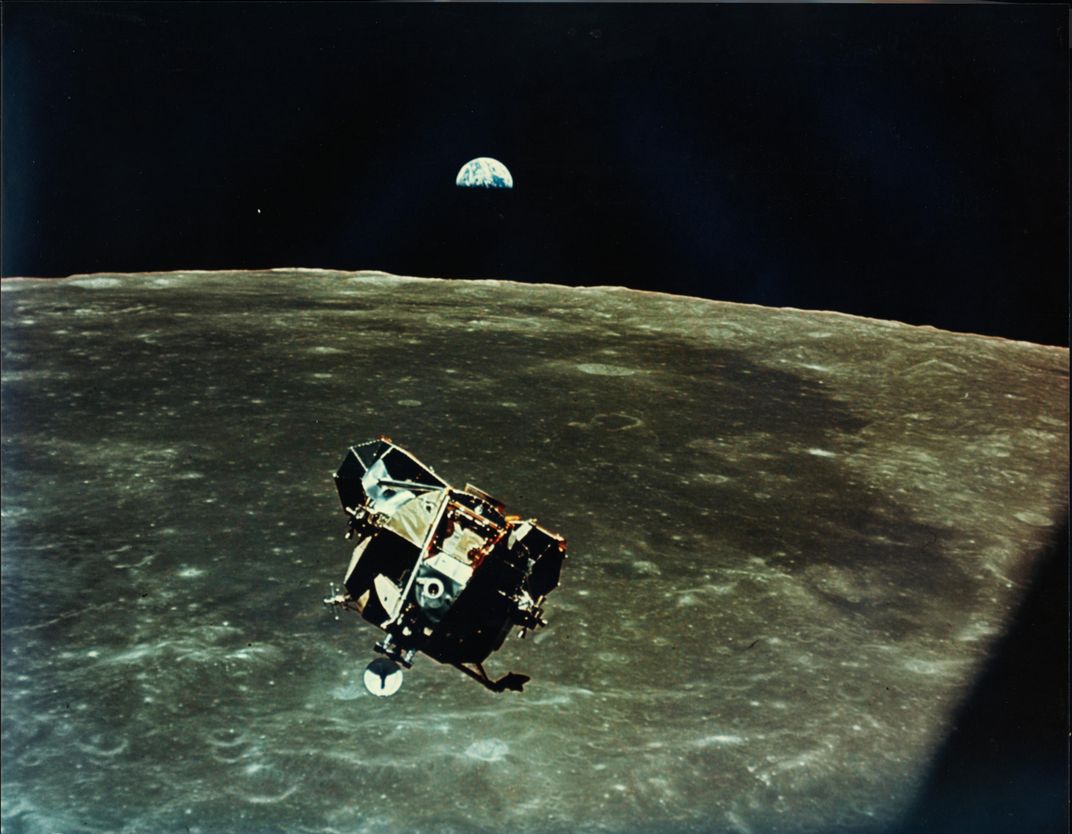

With its stubby body, spidery legs, and gold foil-like skin, the Apollo 11 lunar module looks neither elegant nor airworthy. Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins called it “the weirdest looking contraption I have ever seen in the sky.” But it is the ship that safely carried Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the moon’s surface on July 20, 1969.

The lunar module’s awkward shape was determined by its function. NASA had evaluated three methods of getting to the moon, rejecting two: direct ascent (which required an enormous rocket to ascend from Earth and go directly to the lunar surface, delivering a spacecraft that could return to Earth after the mission was complete), and Earth orbit rendezvous (in which several components would be launched into Earth orbit and docked, and the assembly propelled to the moon).

Instead, NASA decided on a lunar orbit rendezvous. A Saturn V rocket would launch a stack of command, service, and lunar modules into lunar orbit; part of the spacecraft would then descend to the moon’s surface, while the command/service module continued in lunar orbit. Once the mission was complete, the top portion of the lunar lander would leave the moon, return to lunar orbit, and rendezvous with the command/service module; it would be jettisoned into Earth’s atmosphere before reentry.

For the past 40 years, visitors to the National Air and Space Museum have seen the representation of Lunar Module-5—Apollo 11’s Eagle—in the Museum’s east end. It isn’t the actual Eagle (that’s still on the moon), but it is a genuine lunar module, LM-2. It was constructed to fly an uncrewed test in Earth orbit, but the LM-1 Earth-orbit test flights were so successful that the LM-2 flights were canceled. To commemorate Apollo 11’s accomplishment, the lander was modified to look like the one that made the first moon landing.

Now LM-2 has moved to the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall, the first gallery visitors see when they enter the Museum. Currently being renovated, the gallery will include such icons as the Spirit of St. Louis, the Bell X-1, and the North American X-15; it will officially reopen in July 2016.

The LM-2 was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1971 and went on display in the Arts & Industries Building, where it was presented as a surrogate for the Eagle to help visitors better understand Apollo 11’s transformative moment in human history. But curators don’t want to diminish the history of LM-2 itself.

“LM-2 had many lives as an object,” says Museum curator Allan Needell. “NASA wanted to make sure the lunar lander would perform even after the jarring and deceleration it would experience upon landing, so its structural stability and electronic and mechanical systems were tested. And then it was sent to Expo ’70, in Osaka, Japan, to display America’s pride in its accomplishments.”

In its new location, LM-2 will again serve as a surrogate Eagle. “It allows us to tell the Apollo story more broadly,” says Margaret Weitekamp, a space history curator at the Museum. “In the display, the lunar module will be accompanied by NASA’s touchable moonrock, and it allows us to explain to visitors that this is the type of vehicle from which astronauts got out onto the moon’s surface, and were then able to collect specimens like the one you can touch.”

The Museum staff hopes that visitors who see the lunar module will then decide to explore the Space Hall (which tells the story of the Space Race, from Sputnik through the Hubble Space Telescope), or that they might be drawn to Moving Beyond Earth (which talks about the space shuttle and the International Space Station), or head upstairs to see the Apollo exhibit.

“One thing to remember,” says Weitekamp, “is that when the Museum opened in 1976, it had only been four years since the last Apollo mission. That’s the equivalent to putting something on display [today] from 2011. And the Apollo missions had been heavily publicized and televised. We didn’t need to explain Apollo history to our visitors; they knew exactly what they were looking at because they had been watching it on television just a few years before. So one of the challenges that we’ve been working with is the need to provide some context for these objects that would have been self-explanatory 40 years ago, but are now historical.”

Visitors will be able to learn more about the lunar module by watching four new videos that will be available via a mobile app. Running about two minutes each, the videos will highlight aspects of LM-2’s history, including why NASA chose this method of getting to the moon and how the lunar module functioned.

As part of its move, LM-2 is undergoing conservation. Due to light damage, all of the Kapton—the polyimide film that gives LM-2 its golden color—is being replaced. This external layer, explains Needell, allowed Eagle to withstand temperature fluctuations from almost -500 degrees Fahrenheit to 750 degrees.

The Museum is fabricating other pieces that were on Eagle yet are missing from LM-2, including an antenna and part of the control panel. (Each added component is carefully labeled to distinguish it from the original artifact.)

Weitekamp urges visitors to take a moment to look at this unique vehicle. “It was not intended to fly in 1 G; it cannot come back through an atmosphere. It was very much purpose-built to do what it needed to do in space. It’s a pure spaceship.”