The Watches That Went to the Moon

Most common question: Do they contain lunar dust?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/8c/e78c36bb-5690-4a49-8722-1dce99e3fb16/cooper_watch.jpg)

It was a grand watch, a combination timepiece-stopwatch built by Omega to be water-resistant, shock-proof, and able to withstand 12 Gs of acceleration. Most impressive of all: It had flown on Apollo 11, the first mission to land humans on the moon. When Michael Collins, Apollo 11’s command module pilot, was the director of the National Air and Space Museum, he wanted to add the watch to the Museum’s collection. When it was inventoried, however, its serial number indicated it was actually Neil Armstrong’s watch—and had been on Armstrong’s wrist when he landed on the lunar surface. What had happened?

When astronauts return from a mission, space curator Jennifer Levasseur explains, all equipment—including watches—is cleaned and inventoried. When the watches were returned to the Apollo 11 crew they must have gotten mixed up.

Museum director Collins had been wearing the watch to work each day, unaware of the snafu. Meanwhile, the watch that had been listed as Armstrong’s (and was actually Collins’) was out on loan at the Armstrong Museum in Ohio. The Smithsonian quickly sent the correct watch.

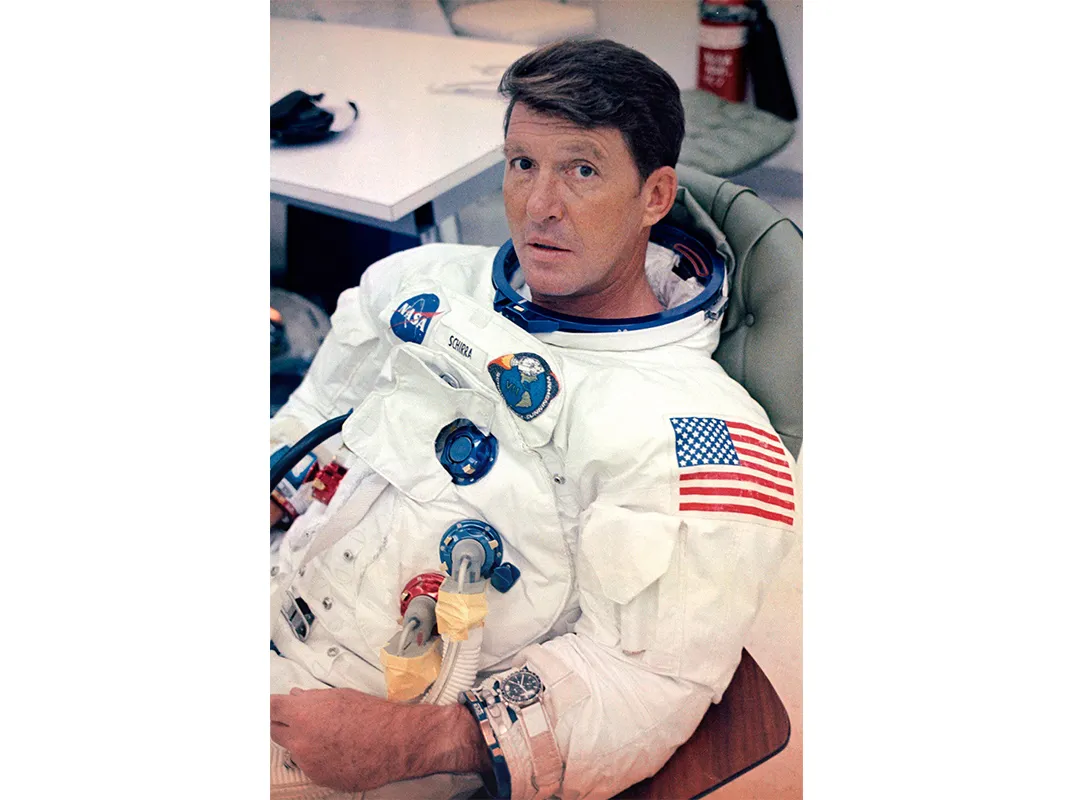

The Omega Speedmaster Professional was chosen by NASA for the U.S. space program in 1965; the model had been worn from the Gemini program into the early space shuttle years.

NASA donated more than 50 of the watches to the Museum in the mid-1970s. Some 35 are at the Museum, with another 17 on loan.

“Omega has always been the official watch of NASA,” says Levasseur. “That is particularly true when it comes to spacewalking. No other watch has ever been flight-qualified by NASA.”

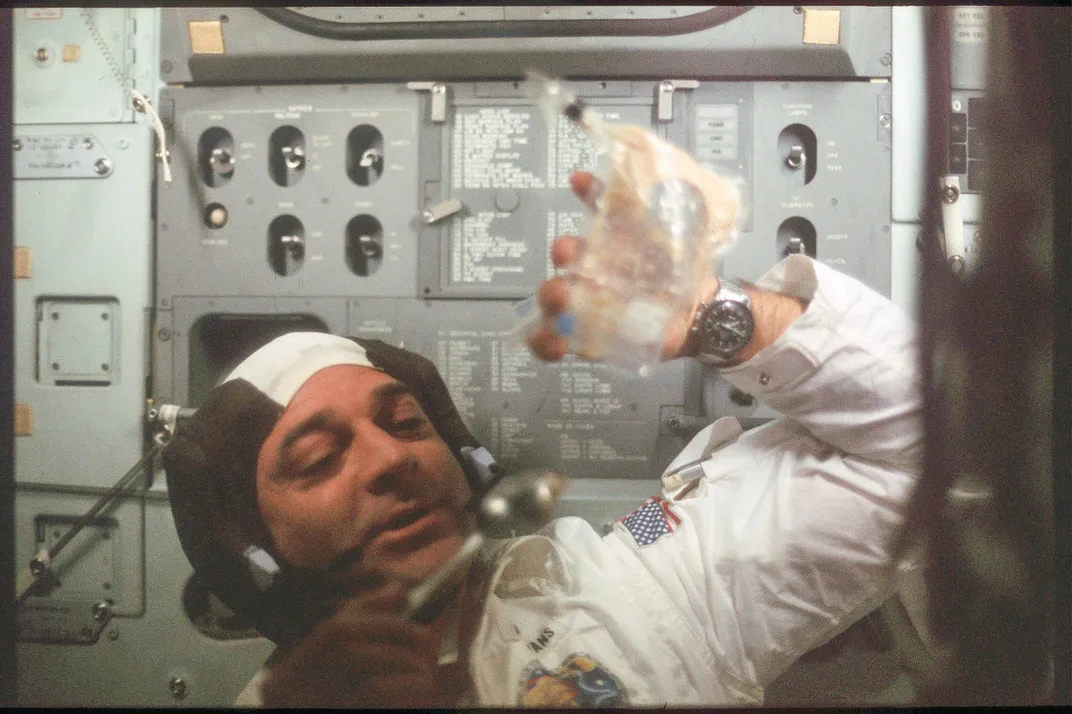

Astronauts eventually asked Omega for a digital display; the watches they were using were battery-less, and had to be wound by hand. But digital watches have either LED or LCD screens. One is sensitive to light direction, the other to temperature—and both become a problem when an astronaut goes outside on a spacewalk. This has led to a new design.

Omega’s new X-33 watch is partly mechanical—it doesn’t require winding—and it has hands like a traditional watch. But it also has a digital background that astronauts can use when they are inside the International Space Station.

Vintage timepieces are a hot topic, says Levasseur, and astronaut watches especially so. Some of the mystique may go back to Buzz Aldrin’s watch, which was lost in 1971 while in transit to the Museum. “I’ve heard a lot of possible stories about where it might be,” Levasseur says. “And that legend has created a sort of an aura around the astronaut watches.” (Seven of the Museum’s watches have been stolen, all while on loan to other facilities.)

Of the visitor questions directed to Levasseur each year, most are about the watches. “People want to know if they contain lunar dust, that’s the most popular question,” she says. (They don’t; any lunar dust on the watch surface was returned to NASA when the watches were cleaned after each mission.) Says Levasseur: “That’s one of the reasons they were chosen in the first place. The construction of the case is so durable that they’re water-resistant, airproof—no material can get inside the watch.”

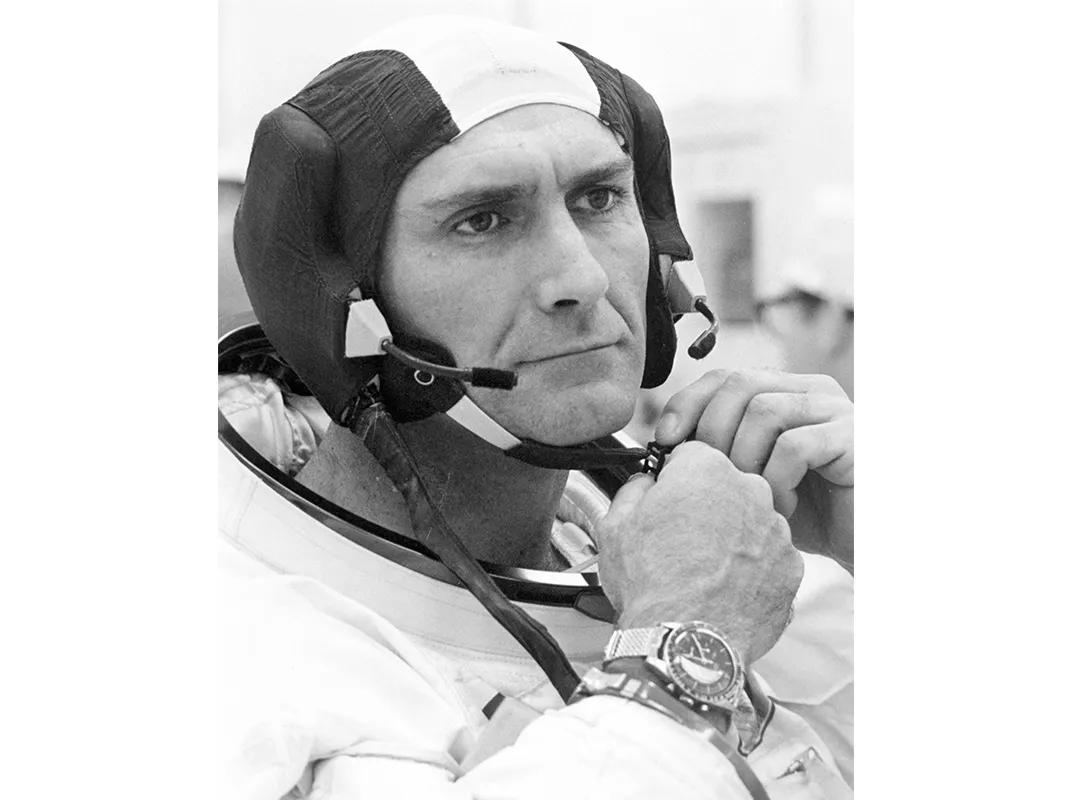

When asked if she has a favorite watch in the collection, Levasseur pauses. “I have a couple of favorites,” she says. “One is Gordon Cooper’s from Gemini 5. It’s the only one in our collection that has a metal band on it. There were two different ways astronauts could wear their watches: with a metal strap, during training, like you’d wear a watch on the ground, or with a Velcro strap. But the Velcro strap would have to go around the spacesuit. There would be a desire to have one fit really well when they were inside the spacecraft [without a spacesuit].”

Her other favorite is the iconic Armstrong watch. “I remember when we did our first conservation on this,” she says. “The tone in the room was different. You’re holding that extra weight of history.”

For the past two years, Petros Protopapas, the director of the Omega Museum, and David Julmy, the Omega Museum’s master watchmaker, have flown from Switzerland to Washington, D.C., to conserve the watches.

“They pay for their own travel; they bring their own supplies, tools, and replacement parts,” says Levasseur. “They are very, very generous to do this.”

During the first visit, in 2013, Alain Monachon, heritage project manager at the Omega Museum, assessed each timepiece in the collection. Subsequent visits will focus on conservation treatment. On one watch’s face, for instance, the luminescent paint is chipping off; it will be conserved during Omega’s next visit.

The partnership between Omega and the Museum was coordinated by the same person who handled the watches at NASA: James H. Ragan. For the last two Mercury missions, the astronauts had worn their own watches. Deke Slayton, then chief of the astronaut office, knew they would need timepieces certified to be able to withstand extreme conditions. Ragan, then a young engineer at NASA, wrote the specification. “It was so nebulous that people couldn’t tell what we were going to do with them,” he says. Ten companies were approached, but after reading NASA’s specifications, only four submitted watches for evaluation; three were selected.

Then began months of testing: vacuum, humidity, vibration, shock. In addition, Ragan gave samples of the three designs to the astronauts, asking which they preferred. After months of testing, only one met all of the requirements: the Omega Speedmaster chronograph. Ragan crossed his fingers, hoping it was the astronauts’ choice too. It was.

Ragan was in charge of all watches from Gemini through most of the space shuttle years. Six months to a year prior to a spaceflight, he gave the astronauts Omega chronographs so they could get used to wearing them. After the missions, they were supposed to give the watches back, but by that time the astronauts considered them personal possessions. When Ragan asked Slayton if he could buy more watches for Skylab astronauts, Slayton said, “Get yourself over here.” (Somehow, in Ragan’s telling, Wisconsin-born Slayton acquires a Texas twang.) When Ragan arrived, Slayton demanded: “What the devil are you buying more watches for?”

Ragan explained.

Slayton replied, “You give me a list of everyone who still has a watch. That’s government property.”

Ragan did so, and legend has it that Slayton sent around a memo directing the astronauts to return their watches to Ragan, or they wouldn’t be assigned any more flying time in the T-38.

Every last watch was turned in.