The Misunderstood Professor

When he suggested in a 1920 treatise that rockets could reach the moon, Robert Goddard sparked a public frenzy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/goddard-0508-631.jpg)

Robert Goddard could scarcely believe his eyes as he scanned the newspaper the morning of January 12, 1920. A young physics professor at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, Goddard had figured that the scholarly paper he gave to the Smithsonian Institution, his sponsor for high-altitude research, might attract attention. But not this: "New Rocket Devised By Prof. Goddard May Hit Face Of The Moon" screamed the front-page headline in the Boston Herald.

Goddard's treatise, "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes," had been released to the public the day before, along with what was then a startling press release from the Smithsonian. Although the original release has not been found, all the major U.S. newspapers across the country quoted from it.

It was mind-boggling news, for two reasons. First, the very idea of flying in space was simply inconceivable when just seven months earlier, in June 1919, Britain's Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown had notched a major milestone in aviation by completing the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic, a 16-hour journey they made at an average speed of 118 mph. Second, the average person in 1920 knew rockets only as the simplest kind of fireworks, something that flew up to 100 feet or so on holidays like the Fourth of July.

But here was the venerable Smithsonian touting a scientist who, the newspaper said, "had invented and tested a new type of multiple-charge, high-efficiency rocket of entirely new design for exploring the unknown regions of the upper air. The claim is made for the rocket that it will not only be possible to send it…beyond the Earth's atmosphere, but possibly even so far as the moon itself."

The Herald article went on to describe the rocket and explain how it could help study the upper atmosphere's chemical composition, temperatures, electrical properties, densities, and ozone content. But the newspaper, and many others across the country, chose to sensationalize what Goddard had intended as a strictly hypothetical exercise: to mathematically demonstrate the possibilities that a multi-stage, unmanned rocket could reach the moon.

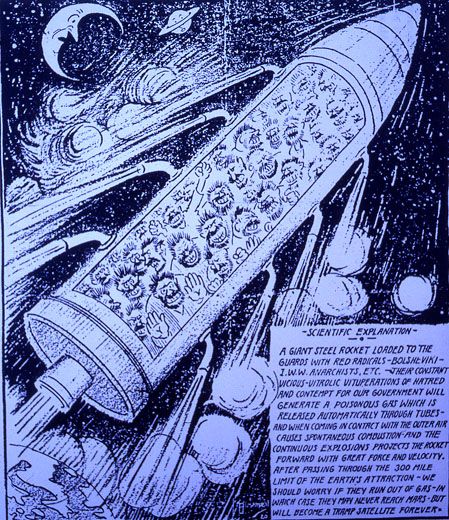

The rocket concept was soon featured in magazines, movies, poetry, cartoons, and even music. Goddard would spend much of his career trying to knock down the misimpressions and rein in what he called "popular fallacies" about his treatise, which never mentioned manned spaceflight at all.

Goddard began his rocketry career in 1899, when at 17 he daydreamed of a spacecraft that could fly to Mars. The vision came to him after he read two serialized stories in the Boston Post, an adaptation of The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells and Edison's Conquest of Mars by Garret P. Serviss. Goddard was so inspired that he vowed to devote his life to seeking a method to get into space.

Unknown to him, about 8,000 miles away, in Kaluga, Russia, a partly deaf schoolteacher named Konstantin Tsiolkovsky had already worked out the possibilities of spaceflight. In 1903, Tsiolkovsky's seminal article appeared in a popular scientific journal, Naouchnoe Obozrenie (Scientific Review). The title of the article, translated, was "The Exploration of Space by Means of Reactive Propelled Devices." The czarist authorities seized the journal because another piece in it was deemed politically subversive, but Tsiolkovsky continued to write about space. His articles were little known even in Russia, mainly because he could barely afford to pay for their private printing. Because of this, and the isolation of Russia from the West, his early works on space were then practically unknown in America.

The young Goddard, meanwhile, while studying for a doctorate in physics, spent years searching for the most practical way to escape gravity. It was not until 1909 that he settled on the rocket as the solution. In 1915, drawing on his assistant professor's salary, he started experimenting with solid propellants. (He switched to liquid propellants in 1921, but did not announce his 1926 liquid-fuel rocket flight—the world's first—until a decade later.)

In 1916, Goddard conducted one of the most significant experiments in his career: He proved that a rocket could work in a vacuum. This was revolutionary: Throughout the 1,000-year history of rocketry, most people believed rockets needed air "to push against." But Goddard's experiments were expensive, and in 1917 he secured a $5,000 grant from the Smithsonian to continue them. He was secretive about his work, saying only that his rockets were for upper atmospheric research.

Later—reluctantly, at the goading of a colleague—he wrote up his results. A Method was a dry, academic treatise, full of scientific formulas detailing his research, including the vacuum experiments. But, out of his fixation on spaceflight and because he thought it would be read only by academics, Goddard included the theoretical exercise of mathematically demonstrating the maximum efficiency of multi-stage rockets. The keys to his rocket's long reach were multi-staging and the use of the de Laval nozzle—a tube with an hourglass shape that accelerates the flow of gas through it.

In all, 1,750 copies of A Method were printed (90 copies went to Goddard), and the Smithsonian sent out its press release to thunder-struck editors. Most of the newspapers regarded the possibility of flight into space via a rocket with intense curiosity. Others treated Goddard's idea with amusement, and ran cartoons about it.

But there were criticisms too, some harsh. The most famous appeared in the New York Times on January 13, 1920, in which an editorial writer accused Goddard of being wrong and uneducated. Titled "A Severe Strain on Credulity," the writer chided the professor for his perceived ignorance: "Professor Goddard, with his ‘chair' in Clark College…does not know the relation of action to reaction, and of the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react." Goddard, the editorial sniffed, "seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools."

Goddard's initial reaction to the furor was summed up in a January 14 article in the Boston Herald. "His invention he will not discuss," the article said, recounting a less-than-fruitful interview that went like this:

Presenting a copy of his treatise to the Herald reporter, Goddard said, "That tells the whole story."

"But this 69-page pamphlet is so abstruse…," the reporter complained.

Goddard simply "smiled pleasantly" and replied, "It seems to me that it would be impossible for me to improve upon the plan."

"Just one question then," the reporter said. "How soon do you expect to be able to go to the moon?"

At this, "the professor began to pace the floor nervously."

"In self-defense," Goddard said, "I have to fight shy of the newspaper men." There was not only the risk of "being misunderstood," he explained, "but my inventions are being perfected under the supervision of the Smithsonian Institution."

That last part was not entirely true. Although the Smithsonian expected and received regular reports of his technical progress, Goddard had complete freedom in his experiments and received no direct technical help from the institution. Goddard had assistants throughout his career, but he never revealed his overall plans to them, and in fact had his workers sign agreements not to reveal details of what they knew of his research.

It wasn't long, though, before Goddard, who subscribed to a news clipping service in New York City, began trying to correct the gross errors he saw in U.S. newspaper accounts of his work. The publicity continued for months, and spread around the world. Newspaper and magazine articles on his moon rocket appeared in Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, and Spain.

Things began to turn bizarre when a Captain Claude Collins of the New York City Air Police volunteered to ride in Goddard's rocket—not to the moon, but to Mars. That, of course, encouraged others. In all, more than 100 people over the years volunteered to ride in the hypothetical rocket. Goddard characterized these people as "adventurers" rather than scientists. In speeches and interviews, he emphasized that it was far too early to talk about humans in space, when what was really needed was fundamental development of the rocket.

Goddard hoped he could turn the flood of unexpected publicity to his advantage and get the public to contribute to his experimentation (he estimated the cost at between $50,000 and $100,000). He was not averse to delivering public lectures on parts of his research, but at one point he complained to reporters, "I could get along a whole lot faster if there was less volunteering and more real support."

Overseas, the public reaction to Goddard's paper was no less enthusiastic. In Russia, enthusiasts first inspired by Tsiolkovsky's works formed rocketry clubs and put on exhibitions to promote Goddard's research throughout the 1920s (see "Russia's Long Love Affair With Space," Aug./Sept. 2007).

After Goddard's paper appeared, it didn't take long for Hollywood to catch moon fever. The first movie to depict a space rocket was All Aboard for the Moon, produced by Bray Studios and released in February 1920. It was a short, animated, educational movie directed by David Fleischer. (Fleischer's brother Max, who did the animation, went on to greater fame as the animator for such characters as Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman.) Film producer John Bray contacted Goddard for technical help, but Goddard politely declined. Undeterred, Bray released a second space movie in 1920, What It's Like to Live on the Moon. Another of his films, 1922's The Sky Splitter, featured a radium-powered rocket that made it onto the cover of the French magazine La Science et la Vie (Science and Life).

Images of spacecraft from the Bray films helped spread the idea of the space rocket to wider audiences, even if the message distorted what Goddard was actually suggesting. Goddard's treatise clearly had an impact on movie makers of his day; before 1920, films about space did not have rockets at all. Georges Méliès' classic 1902 movie LeVoyage dans la Lune (The Voyage to the Moon), featured a giant cannon as the launcher. By contrast, a publicity photo for the 1922 film Chasing the Moon showed star Tom Mix straddling a moon-bound rocket. The movie went out to more than 20,000 exhibitors in a dozen countries.

Early science fiction literature also toyed with the space rocket idea, but it took the publication of Goddard's treatise on rocketry for the idea to take hold in that genre. In a compendium edited by Everett Bleiler of more than 3,000 science fiction stories, the earliest mention of the rocket as a means of travel into space was in Cyrano de Bergerac's novel The Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon, published in 1656. But considering that the title contained the word "comical," it was easy to dismiss de Bergerac's concept of the rocket as little more than a humorous literary device. His spacecraft, in fact, was only a box lifted up by ordinary fireworks.

Overall, the compendium showed that before 1920, only about five space stories featured rockets. Before Goddard, the most popular means of space propulsion in science fiction was anti-gravity, as featured in H.G. Wells' First Men in the Moon, published in 1901. The situation changed dramatically after 1920, with the appearance of the world's first sci-fi magazine, Amazing Stories, in 1926. For the next decade, the rocket was the preferred method of imaginary travel, appearing in 169 science fiction magazine stories, more than any other type of vehicle.

Adding to the rocket frenzy of the 1920s was the impact of another rocket pioneer, Rumanian-born (later German) physicist Hermann Oberth, whose book, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket Into Interplanetary Spaces), appeared in 1923. In many ways Oberth's book was far more advanced than Goddard's work, although it was strictly theoretical. For one thing, Oberth focused on the potentially more powerful and controllable liquid-propellant rocket, compared with Goddard's initial, solid-fuel rocket. For another, Oberth stressed human spaceflight, while Goddard had written of the unmanned rocket.

From the 1920s to the 1940s, Goddard's name was invariably brought up worldwide in any literature having to do with rockets. But from 1930 on, almost without interruption, he had become—except for a few assistants—the lone rocket experimenter at his isolated research station near Roswell, New Mexico, funded by the industrialist Daniel Guggenheim. In the end, Goddard preferred secrecy to publicity, and he remained aloof from an ever more crowded field of rocket experimenters until his death in 1945.

Although unintentionally, Goddard's treatise planted the seeds, both conceptual and technological, of the Space Age. While Goddard did not live to see that age unfold, his ideas were eventually accepted even by his critics. Almost 50 years after the New York Times had so blistered Goddard, it conceded in an editorial: "Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Isaac Newton, and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in the atmosphere. The Times regrets the error." The retraction ran on July 17, 1969, as Apollo 11 streaked to the moon.