Why Earthlings Are Attracted to Mars

How science fiction and history keep pulling us to the Red Planet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/why-mars-aug-2012-3_FLASH.jpg)

Adapted with permission from Imagining Mars: A Literary History by Robert Crossley, Wesleyan University Press, Copyright Robert Crossley, 2011.

In August 2003, when Mars and Earth drew closer together than they had been for 6,000 years, I was deep into the research for a literary history of Mars. Earth and Mars routinely align in what astronomers call an opposition, with Earth in the middle and Mars and the sun on opposite sides. It occurs every two years, but only rarely when Mars is at its nearest point to the sun. Having had the thrill of examining Percival Lowell’s historic Clark Refractor at the observatory he founded in Flagstaff, Arizona, I wanted to celebrate the 2003 opposition by looking at Mars through the closest cousin available to me in the Boston area.

I headed for Wellesley College to look at the planet through the Whitin Observatory’s superb Victorian-era Fitz/Clark 12-inch refractor. “Public nights” at the Whitin are usually modest events, and I anticipated having the telescope largely to myself and a few others. Wrong. I arrived to find several hundred Mars enthusiasts patiently standing in line for a turn at the eyepiece. Every now and then as Mars peeked out from the passing clouds, a cheer went up. Around midnight I reached the head of the line and had 30 seconds to savor the quivering image of the planet next door before yielding to the person behind me. Though the moment was brief, that evening gave me a fresh appreciation of the durability and critical mass of public fascination with Mars.

For most of my life I never reflected on the significance of my own longstanding curiosity about Mars and Martians. It was just part of the air I breathed. Like many in my generation, I had been enthralled as a kid by seeing Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars at Saturday movie matinees. I had also often heard my father tell the story of the frightening 1938 radio broadcast of Orson Welles’ adaptation of The War of the Worlds, and I had read books of popular science still illustrated with Lowell’s maps of Mars, long after his canals had disappeared from genuine scientific discourse. Sometime in my adolescence I discovered The Martian Chronicles, Ray Bradbury’s highly romanticized tales of Americans on Mars; his purple prose seemed not entirely unlike the lush lyricism of Keats’ poetry, which I was also then discovering. I felt no conflict between my awakening to “serious” literature and my love for Bradbury’s fantasies.

“No Martian can escape the past; we are told tales in our infant beds,” writes a 22nd century woman living on Mars in Greg Bear’s 1993 novel Moving Mars. Storytelling, as Bear’s character testifies, has shaped our awareness of Mars perhaps as much as scientific investigation. But I was unaware of how deeply the tales I’d heard about Mars in my childhood had seeped into my psyche. At age 50, that changed. I was teaching a course on the history of science fiction, and, reviewing my syllabus, I noticed that four of the 10 novels I was slated to teach had Martian settings. It had not been a conscious choice. Once I realized how large a presence Mars was going to have in my classroom, I knew I needed to offer my students a context for understanding Mars as a phenomenon in cultural history. I set out to construct a timeline of the scientific and literary milestones in our knowledge of Mars. For the first time, I grasped the centrality of the Great Opposition of 1877, when astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, drawing what he saw through his telescope, sketched a map of Mars covered in a latticework he labeled “canali.” Percival Lowell’s imaginative interpretation of Schiaparelli’s map infuriated scientists for decades, but the stories that created the American fascination with Mars began here.

Soon after I embarked on my study, the world of science experienced a reprise of the controversy engendered by Schiaparelli’s sketches. The great debate in 1996 was started by the Antarctic meteoroid ALH84001: It came from Mars, but did it contain fossilized Martian bacteria? Suddenly the issue of life on Mars—largely dormant in scientific circles for decades but still a lively scenario in fiction—was in the forefront of public awareness of our missions to Mars. At my university, I led a colloquium with a colleague from the biology department. We gave it a title meant to be provocative: “Mars: Desire vs. Evidence.” Ever since graduate school, I had been impatient with the notion that there was an unbridgeable gulf between the “two cultures” of literature and science. The colloquium and the other debates of 1996 proved, to me at least, that the gulf can be bridged and that explorers of Mars, in all disciplines, have a better chance of understanding the planet if they examine the relationships between the Mars of our dreams and the Mars that’s actually there.

By the time I came to this realization, I was eagerly revisiting my youthful romance with Mars, but now fortified by habits of scholarly research. I wanted to know just how many novels had been written about Mars, and I started educating myself about the planet’s astronomical studies. With a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, I undertook serious work in 2000, and soon had a revelation foreshadowing that evening at the Whitin: I had no idea how vast the literature of Mars would turn out to be.

I haunted the Boston and New York public libraries, read microfilms at the Library of Congress, hunted down copies of long-forgotten novels in antiquarian bookshops and on eBay. Utopian Mars, feminist Mars, satirical Mars, boys-adventure Mars, Arabian Nights magic on Mars, Robinson Crusoe transferred to Mars, Thomas Edison on Mars. The abundance of Martian fiction was astounding, overwhelming. And some of it was wildly bizarre, particularly the travelogues written by psychics and mediums who did not think they were writing fiction and who claimed to have mastered the Martian language.

Early during my NEH year, I enjoyed a week’s residency at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, where, as the only humanist among the visiting astronomers, I got to see how differently but not incompatibly literary and scientific scholars do their work. We all lived in the chateau for visiting researchers; each morning as I finished breakfast and headed for the library, the astronomers came trooping in from their night on the high desert, hungry for dinner. In the Lowell Archive, I pored over the amateur astronomer’s correspondence with scientists who disputed his findings and the voluminous fan mail from laypeople around the world who adored his obstinate claims of Martian civilization.

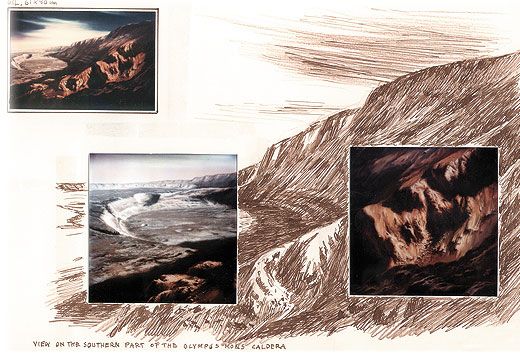

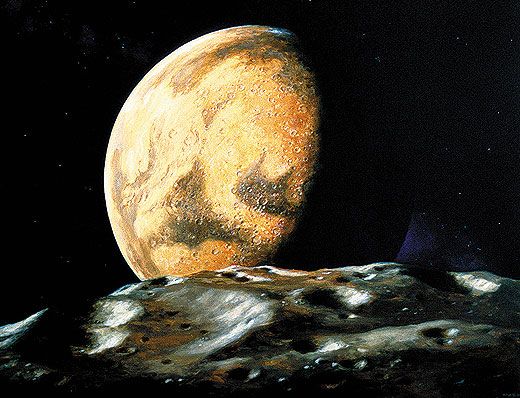

Here in the 21st century, long after the heyday of Lowell’s Mars, the romance with the planet remains undiminished. The attraction is still partly topographical, but Lowell’s imaginary waterways have been replaced by U.S. Geological Survey maps that define this great wilderness planet with canyon systems, giant volcanoes, craters, and dried riverbeds. Many can be viewed on a computer screen: In 2009, Google Earth, with help from NASA and the USGS, created a three-dimensional image of Mars for anyone to zoom in on. And questions about life on Mars remain: Was there ever any? Might there still be microbes beneath the polar caps or in underground reservoirs? Will there be organisms in the future, imported from our planet?

While the exotic terrain and biological mysteries are real attractions, I suspect another explanation for our being Mars-struck—and it goes back to stories we were told as children. Kim Stanley Robinson, the unsurpassed chronicler of Mars in contemporary fiction, evokes our human nature as creatures endowed with language and imagination. At the opening of Red Mars (1992), the first of his three magnificent novels about the settling of Mars over the next couple of centuries, he reminds us, “We are still those animals who survived the Ice Age, and looked up at the night sky, and told stories.”

Our fascination with Mars is fed by fiction writers who have long known that a great story—multiple stories, really—could be made from popular fantasies as well as popular science. Some earlier novelists tried giving ballast to their Martian inventions by citing Lowell’s theories, even incorporating his maps into their fiction: They appear as a gilded stamp on the cover of Mark Wicks’ To Mars via the Moon (1911), are carved into a palace floor in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars (1912), and come into view at the end of C.S. Lewis’ brilliantly unscientific Out of the Silent Planet (1937). With or without Lowell, over the past century or so, H.G. Wells, Alexander Bogdanov, Philip K. Dick, Frederik Pohl, Ben Bova, and scores of other writers have kept Mars alive for us. The storytellers give Mars mythic dimensions. Compared to the way astronomers and planetary geologists have observed the planet, writers train a different kind of eye on Mars: the mind’s eye.

The myths will never substitute for the science of Mars, of course, but myths can draw popular attention to the science. As far back as 1839, an unknown British author believed that fantasy, rendered in his book A Fantastical Excursion into the Planets, would inspire young readers to serious astronomical study. We now know that some famous scientists traced their careers to adolescent delight in literary images of Mars and Martians, however wrongheaded those images may have been. Rocket pioneer Robert Goddard read The War of the Worlds in his teens, and it fixed his attention on space. As a young man, Wernher von Braun was captivated by the great German Martian novel Auf Zwei Planeten (1897), and when Kurd Lasswitz’s book finally appeared in English translation as Two Planets five years before von Braun’s death, he supplied its epigraph: “From this book the reader can obtain an inkling of that richness of ideas at the twilight of the nineteenth century upon which the technological and scientific progress of the twentieth is based.” Carl Sagan admitted, unabashedly, that he was inspired by the cheesy exploits of Burroughs’ John Carter in A Princess of Mars.

From the 1890s to the present day, Mars mania has ebbed and flowed but never dried up. When it comes to the subject of Mars, the traffic between literature and science is spirited, if occasionally irritating to those who prefer their science uncontaminated by myth and their fiction unencumbered by facts. But when people with little knowledge of hard science read Martian fiction, they sometimes become curious about the actual planet. Astrogeologist Bruce Murray, a leader of the scientific teams for the Mariner missions of the 1960s and 1970s, attributed the willingness of taxpayers to support Mars exploration to the excitement generated by writers like Burroughs, Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke.

Mars in the mind’s eye is almost bewilderingly various: from the horrors of The War of the Worlds in 1898 to the goofily vulgar comedy of Fredric Brown’s Martians, Go Home (1955); from whimsical dreams of reincarnation on Mars in Camille Flammarion’s Uranie (1889) to the gritty realism of the Czech writer Ludek Pesek’s account of the first expedition to Mars in The Earth Is Near (1971); from the masculinist and nationalist absurdities of Gustavus Pope’s 1894 Journey to Mars to the ecological consciousness of Frederick Turner’s astonishing epic poem of terraformation, Genesis (1988).

From this cornucopia of Martiana, take two instances of how Mars has been imagined. Fredric Brown’s Martians are at once comic originals and a pastiche of pulp-fiction motifs. By the 1950s, many of the classic science-fictional themes had been worked out, and Martian fiction, especially, seemed to have come to a dead end. Brown’s solution is to embrace banality, and he fashions his Martians in the most degraded of popular images: little green men—but unlike any that had appeared in print before. Grouchy, foul-mouthed, sneering, they have learned everything they know about terrestrial culture by eavesdropping on radio programs, so they call everyone in the United States either “Mack” or “Toots.” They take pleasure in exposing secrets, whether poker hands or classified documents, and a principal effect of the invasion is the termination of cold war East-West hostilities.

At the other end of the spectrum, Ludek Pesek’s The Earth Is Near may be the most gripping fiction about Mars between Bradbury’s Chronicles at mid-century and the outpouring of major works by Robinson, Gregory Benford, Ben Bova, and others in the 1990s. Stimulated by the Mariner 4, 6, and 7 photographs, Pesek’s vision of Mars is more drab and desolate than what the breathtaking landscapes disclosed by Mariner 9 and the Vikings would have suggested to him. Relentlessly anti-nostalgic, The Earth Is Near captures the difficulties, dangers, obsessions, and monotony of extraplanetary work. “An expedition to Mars,” its narrator writes, “is not a dream but a life and death struggle.” The ubiquitous dust causes more headaches than the mission designers anticipated; it fouls filters, seeps into clothing, clogs pressure chambers, disables scientific instruments. The crew spends so much time in suits and helmets, their eyes and expressions indiscernible, that they grow isolated from one another. And yet, paradoxically, this unromantic portrait of a hostile environment, this subversion of a whole tradition of Martian adventure fiction, itself contributes to our romantic fascination with the sheer otherness of Mars.

The literature of Mars includes many works that exhibit the highest standards for imagination, style, scientific fidelity, and grandeur of vision. Others make smaller claims on our attention. But this huge and uneven body of work teaches us the value of seeing with the mind’s eye. The literary images of Mars, some outdated and some strikingly current, some scrupulously incorporating scientific data and others willfully anti-scientific, have ensured that NASA’s missions to Mars have a large, attentive, often well-informed, and eagerly curious audience.

Robert Crossley, after 37 years in the English department at the University of Massachusetts, is professor emeritus.